Hurricane Milton and this Climate Moment

Legal Planet: Environmental Law and Policy 2024-10-10

When President Biden addressed the nation yesterday from the White House, he warned that Hurricane Milton could be one of the most destructive storms in more than a century, but he stopped short of explaining why — that climate change, fueled by our burning of fossil fuels, is making oceans warmer and storms stronger, capable of metastasizing monstrously.

It’s understandable for the outgoing president to focus on marshaling the National Guard, Coast Guard, and firefighters to rescue, recover, and rebuild — but American audiences need to hear the why and they need it now from trusted sources… Whoever’s left, that is.

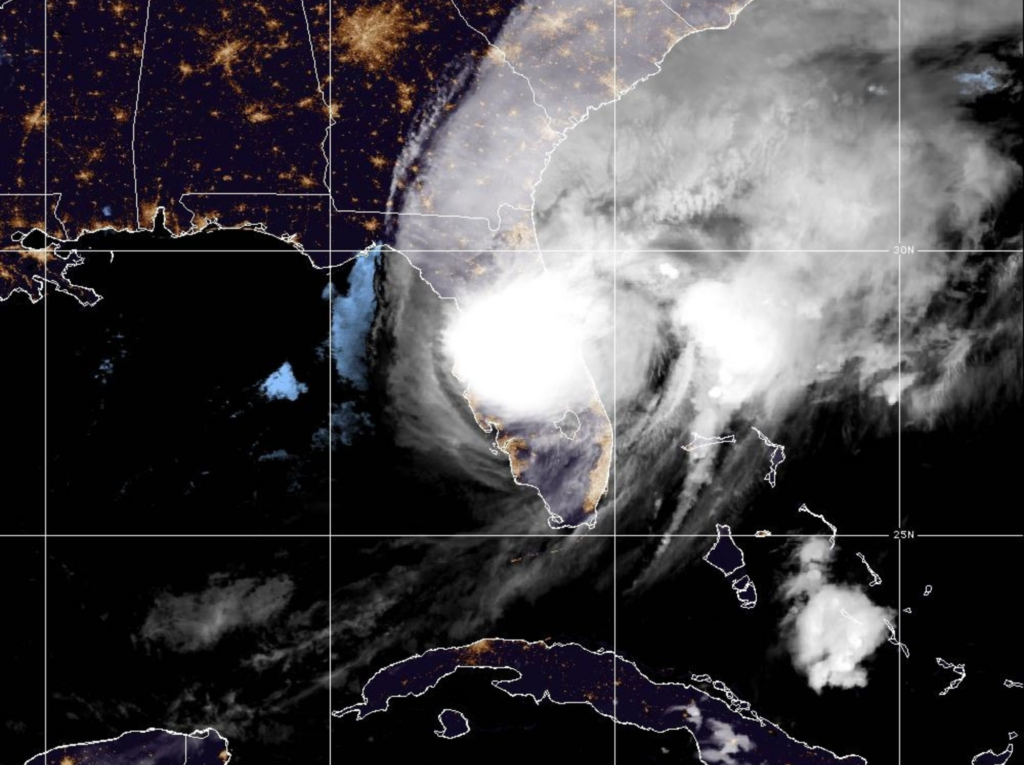

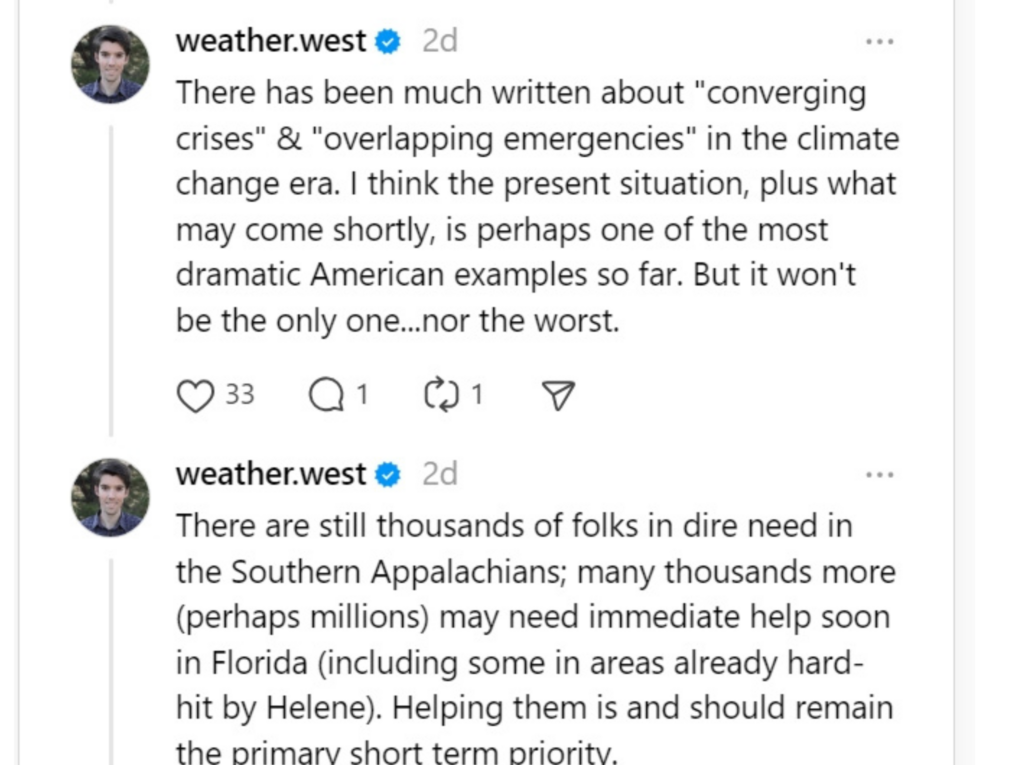

This is a moment of reckoning. A “critical and unpredictable new phase of the climate crisis” as several leading climate scientists wrote in an article in the journal BioScience published on Tuesday. We’re seeing that “the new normal is that there is not going to be a new normal,” the New Yorker’s Elizabeth Kolbert wrote this week. “We are living in a new abnormal; storm after storm these are more intense… driven by the warming of the climate,” Democratic Rep. Kathy Castor of Florida told NPR, proving you can in fact touch on both recovery efforts and climate change in a 3-minute interview. “We are witnessing a genuinely extraordinary, and regionally quite deadly and destructive, period for extreme weather in the United States,” Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, posted to social media, noting that “the fingerprints of climate change are all over” these recent, overlapping emergencies between Hurricane Helene and Milton, not to mention wildfires in the west.

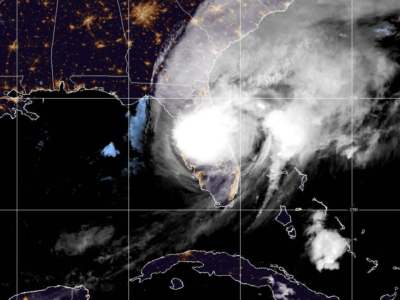

Milton brought 10-foot storm surge and tornadoes. Three million people are without power. More than 5.5 million people were under storm surge warnings and more than 13 million under a flood watch. Imagine losing your house to a hurricane a week ago and moving into a mobile home only to be forced to evacuate from your trailer? The wind even destroyed the roof of the Tampa Bay Rays’ stadium, while it was being used to house thousands of emergency workers.

FEMA is stretched thin. If another disaster were to occur, less than 10% of agency staff would be available to respond. And even though they have the money for these relief efforts, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said this week that FEMA would not have the funds to get through the rest of hurricane season, through November. Yes, Speaker Mike Johnson could bring the House back into session to deal with this emergency, but let’s face it: Congress is not going to do anything with voting already underway in the presidential election. One candidate is exploiting the climate chaos to spread disinformation to gain a political edge. It’s as if we needed a reminder that the 2024 election is a climate emergency election.

We have known, of course, the name of Hurricane “Milton” for months, ever since the World Meteorological Organization selected the names for this hurricane season, which we knew was likely to be historic when the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration predicted an 85% chance of an above-normal hurricane season. Along came Helene, a historic storm itself, which was described as the Katrina of 2024 and then came Hurricane Milton, which underwent one of the most rapid intensifications ever seen in the Atlantic. NBC meteorologist John Morales went viral for tearing up and emotionally describing how rapidly Milton has grown, due to climate change. In a cruel irony, the wing of NOAA that catalogs the country’s billion-dollar disasters is still crippled because it’s based in Asheville, North Carolina. We just learned that hurricanes are hundreds of times deadlier than anyone has realized according to a study published last week in Nature. Climate reporting has been indispensable the last two weeks, but it has hit a moment of reckoning too. “Climate havens don’t exist: sponsored by Chevron” was the unfortunate Politico newsletter placement that renewed good questions like Why is Chevron sponsoring Hurricane Helene journalism? The appropriate meme response: “Hurricane Helene, sponsored by Chevron.” Meanwhile, the Governor of Florida is presiding over this climate emergency months after signing legislation to erase “climate change” references from state policies and now is taking the personal phone number of the president so that he can be in constant contact for federal support. Will Gov. DeSantis and other Republican leaders accept federal money to rebuild destroyed infrastructure? Of course they will. It’s not unlike the Republicans who trash the Inflation Reduction Act and then ask for hundreds of millions of dollars from Biden’s climate law for their district — “vote no and take the dough.”

All of this is both shocking and not surprising. And yet no one quite predicted that extreme weather, climate science, national news and politics would be on such a dramatic collision course this October. Now, we even need online guides for how to vote during a climate disaster.

Once the waters recede, the question of “Who pays for all this?” will become even more important. Depending perhaps on the outcome of the election, two separate but related efforts to create climate funds will be interesting to watch. The first is the “Make Polluters Pay,” movement, in the form of the NY climate superfund bill that passed both the State Senate and Assembly but needs the governor’s signature. Massachusetts, and Maryland also have pending bills, and there’s federal legislation in Congress introduced a month ago to “require the biggest polluters to begin paying their fair share to confront the climate crisis.” The second is the long-running legal effort to bring state lawsuits against Big Oil for allegedly lying about their products and the risks of climate change for decades. The Supreme Court on Monday asked the U.S. Solicitor General to weigh in on whether they should allow 19 Republican-led states to try to block five Democratic-led states from pursuing lawsuits over climate change against major oil and gas companies in state courts.

These are topics for today.

Because as my UCLA colleague Daniel Swain writes, helping the disaster victims is the priority short-term and “yet if we can’t also manage to have the harder conversations regarding natural hazard risk and disasters and climate change in the moments when people are actually paying attention, we’re never going to solve any of the underlying problems,” Swain says. “I firmly believe we can, and must, do both.”