Environmental Law and the Gun Debate

Legal Planet: Environmental Law and Policy 2013-01-03

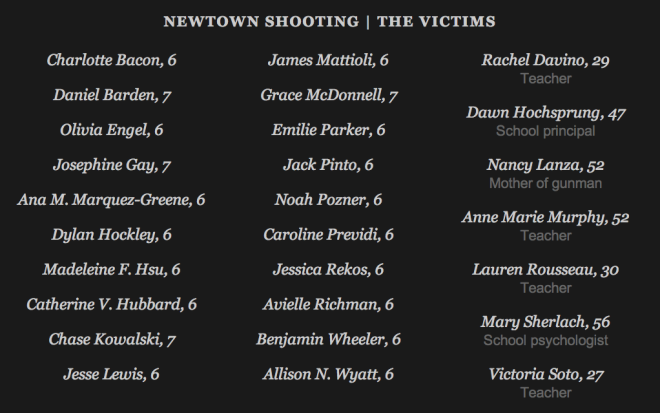

The horrifying events in Newtown have predictably led to calls for new gun controls, which have predictably led to push-back from gun rights advocates — some measured, some certifiable.

The horrifying events in Newtown have predictably led to calls for new gun controls, which have predictably led to push-back from gun rights advocates — some measured, some certifiable.

For the most part, this debate has nothing to do with environmental law and policy, but there is an exception. The New York Times had an important story last week about the sometimes bizarre and outrageous constraints placed on the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) in collecting data about gun use and purchases. ATF is forbidden from maintaining an electronic database of gun purchases, has been starved of funding, has gone without a full-time director, cannot share gun tracing information in many circumstances with state and local law enforcement, and is restricted in when it can even perform basic law enforcement compliance checks for federal firearms licensees.

Gun rights advocates are not sheepish about such controls, of course. They are proud of them:

David Kopel, a lawyer and the Second Amendment project director at the Independence Institute, a research group concerned with individual choice, said Congress was aware that a registry could be misused. “We don’t have an automated database of everybody who’s had an abortion or of anyone who owns controversial books,” he said.

Kopel’s point is particularly interesting because of its analogy between conscience, or bodily privacy, and gun ownership. If we accept that analogy, then we should accept the lack of law enforcement power in this area.

But we need not accept that analogy, which is where environmental law comes in. Consider the right to private property, an area long studied by environmental legal scholars because of its constitutional status in the Takings Clause. Private property rights are carefully protected in the United States. Even the Heritage Foundation, the right-wing political organization, concedes that such rights are strongly protected in America. Its “index of economic freedom” gives the United States high marks for private property protection, and if anything that is understated given Heritage’s ideological agenda.

Private property, however, is subject to vast regulation in the United States. Indeed, local land use authority — perhaps the most crucial area of litigation under the Takings Clause — is perhaps the most over-regulated sector in American public policy. Doing anything with your land usually requires a government permit, and building on it requires a series of permits and inspections from public officials. Yet this hardly means that private property is not protected. Far from it.

The gun/property analogy is better than the gun/conscience analogy because sometimes property is sometimes in a public way and sometimes in a private way. If you are just existing on your property, the government’s ability to regulate and survey you is restricted. But if you want to sell or develop your property, then you are emerging into a public sphere and are subject to more regulation. Similarly, if people simply have guns at home, then the government might have less authority to regulate. But if people are selling guns, then they are emerging into the public sphere, and the government can regulate. It gets tricky, because even if someone simply has a gun at home, it is a potentially dangerous object in a way that conscience is not, or abortion is not. But if anything, this again shows the essentially public character of guns in the same way that rights to property have an essentially public character, and thus show a need for more governmental regulation.

It is hardly perfect, but analogizing guns with property demonstrates that we need not choose between the protection of civil rights and government regulation. We really can have our cake and eat it, too. Perhaps that is a bit of hope for the new year.