Governor Newsom’s CEQA Bills Could Be a Modest Step in the Wrong Direction

Legal Planet: Environmental Law and Policy 2023-07-18

Credit: Cambridge Historic Commission (CC BY 2.0)

Credit: Cambridge Historic Commission (CC BY 2.0)Speaking to Ezra Klein in late June, Governor Gavin Newsom hearkened back to the California of the 1950s and 1960s: “People are losing trust and confidence in our ability to build big things. People look at me all the time and ask, ‘What the hell happened to the California of the ‘50s and ‘60s?’”

Governor Newsom spoke to the New York Times columnist as part of a larger media push to promote his package of eleven trailer bills––submitted alongside his proposed budget for California––ostensibly designed to expedite infrastructure development, meet California’s climate goals, and capitalize on the wealth of federal dollars available through recent infrastructure bills. As the Legislature debated the merits of the package, the two bills that received the most attention were amendments to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The first of these bills reduced the time allotted for CEQA litigation to 270 days for certain energy and infrastructure projects. The second amended CEQA’s administrative record provisions by reducing the time for record preparation from 90 to 60 days; allowing project proponents (rather than CEQA petitioners) to seize back the right to prepare the record; and excluding from the record communications between agency staff members that did not reach the ultimate decision-makers. Just last week, Governor Newsom signed an amended version of this package into law, with the CEQA bills passing through largely untouched. (Notably, environmental groups were pleased to see the “Fully Protected Species Trailer Bill,” which our Deputy Director Julia Stein wrote about back in May, receive significant amendments).

But if the governor’s tone in that opening quote came off as defensive, that’s probably––at least in part––because the CEQA bills generated controversy on both sides of the reform conversation. Environmental and environmental justice groups, and certain members of the Legislature, took issue with both the substance of the bills and the expedited process through which they were adopted. But proponents of CEQA reform criticized the bills as overly technical, duplicative, and generally unambitious.

So which group is right about the bills?

Both are, to some degree. As a professed CEQA Truther, I agree in principle with most of the points that environmental and environmental justice groups made about the problems raised by both trailer bills. The judicial streamlining provisions mean tighter litigation timelines in CEQA cases, which will inequitably disfavor less well-resourced CEQA litigants. These disfavored litigants will often be the environmental justice groups and low-income or BIPOC communities that frequently rely on CEQA due to their regular exclusion from siting and permitting decisions. These same communities experience cumulative environmental burdens caused by a racist history of land use siting practices. While the judicial streamlining bill doesn’t directly affect CEQA’s environmental review provisions, an expedited litigation timeline could still put smaller, community-based organizations at a disadvantage.

I have deeper concerns with the administrative record provisions. The administrative record generally makes up the universe of evidence available to the parties in a CEQA case; and this record can end up being very long. Consequently, cutting down the length of time for parties to prepare the record may lead to the exclusion of relevant documents. More critically, exempting internal agency emails not reviewed by decisionmakers from CEQA’s record requirements runs counter to CEQA’s fundamental principles of transparency and accountability. Even where internal communications never make it to decision-makers directly, those emails may inform the agency’s public discourse and environmental review, shape staff recommendations to decision-makers, and provide a window into underlying agency motivations and conduct. Moreover, because the administrative record streamlining bill authorizes agencies and project proponents to retake control of the record preparation process, those agencies have greater latitude to pick and choose which documents are included in the record. As noted in Golden Door––a recent CEQA case that the administrative record bill now overturns––allowing agencies to determine what does and does not belong in the record can “enable an agency to prune the record by deleting unfavorable internal agency communications.”

Despite these valid concerns, the actual effect of the CEQA trailer bills will likely prove less dramatic than the strong rhetoric they’ve generated. Courts largely have discretion to determine whether to follow the expedited schedule. In fact, the 270-day timeline laid out in this trailer bill dates back to 2013, when Senate Bill (SB) 743 (Steinberg) fast-tracked CEQA lawsuits on Environmental Leadership Development Projects, a segment of projects including clean renewable energy projects, clean energy manufacturing projects, and––as later amended by SB 25 (Caballero, 2019) and SB 7 (Atkins, 2021)––infill housing and LEED-certified developments. Like these streamlining bills, the judicial streamlining trailer bill requires courts to resolve cases within 270 days only “to the extent feasible,” without imposing any penalty for longer review periods. As such, cases subject to 270-day judicial streamlining are often not resolved within the allotted time period, even though all CEQA cases already receive calendar preference under existing law. Even more fundamentally, the judicial streamlining bill does not touch on housing, which is often the most contentious piece of the CEQA debate.

Lithium mining is among the projects that could be eligible for expedited judicial review. Credit: Reinhard Jahn (CC BY-SA 2.0 DE)

Lithium mining is among the projects that could be eligible for expedited judicial review. Credit: Reinhard Jahn (CC BY-SA 2.0 DE)And despite my stronger concerns relating to the administrative record trailer bill, I’m unsure how often project proponents and agencies will actually invoke this bill. Project proponents availing themselves of the opportunity to prepare the administrative record will have to pay the (sometimes expensive) cost of record prep themselves, regardless of outcome. And CEQA petitioners will often be able to review documents relating to the project through the California Public Records Act and resolve disagreements on what belongs in the record through record disputes. Further, where the 60-day timeline provisions for record certification become overly burdensome, they can be extended by court order or stipulation of the parties, which already occurs with some regularity, even under the 90-day timeline (although the trailer bill provides that courts may only extend this window “for good cause”).

I’m still wary of the provisions excluding internal agency communications from the record, which will likely be most consequential where agencies support their decisions with post hoc or pretextual reasoning, or otherwise act in bad faith. For instance, in the past, agency emails have revealed agencies’ awareness that a project would be larger in scope or impact than considered in an environmental impact report (EIR). And while these concerns are legitimate, I’m not convinced that they will be relevant as often as others have argued, since most CEQA disputes are evaluated solely on the quality of publicly released environmental review documents, not on agencies’ internal deliberations.

In fact, my ultimate takeaway from these bills is one of very few times I have found myself in modest agreement with Ezra Klein, who called the infrastructure package as a whole “a collection of mostly modest, numbingly specific policies.” But if I have such tepid feelings about the substance of these bills, why did I dedicate a Legal Planet post to this infrastructure package?

Back To the Opening Quote

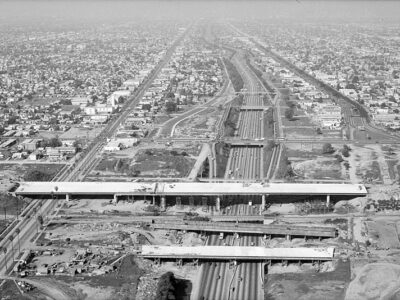

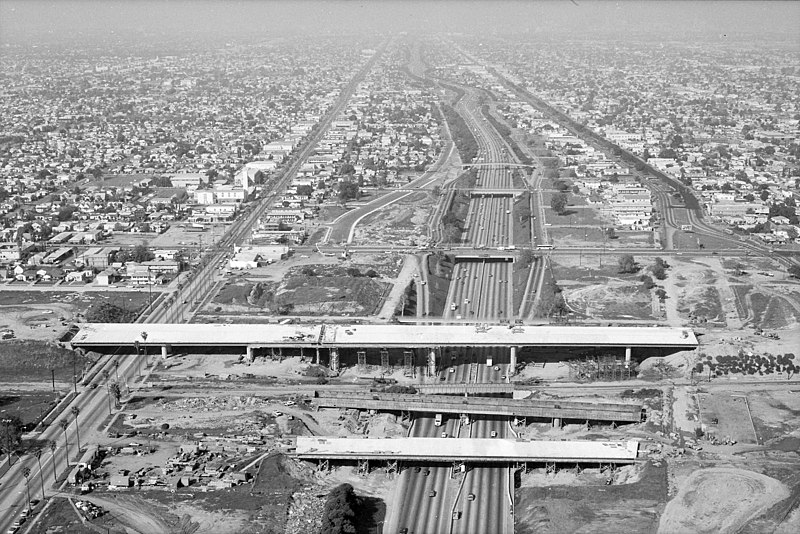

Governor Newsom’s quote was telling. “What the hell happened to the California of the ‘50s and ‘60s?” I don’t think it’s a coincidence that he refers to these decades and that the California Legislature passed CEQA in 1970.

As a vigorous, longtime advocate for significant CEQA and permitting reform, Klein seemed to express sympathy for Governor Newsom. But for me, the “big things” of those decades––like expansions of California’s water system, freeways, and university structure––signify economic growth at the expense of California’s most vulnerable groups. During those decades, building “big things” in California often meant displacing and contaminating communities of color. These infrastructure projects meant building networks of freeways cutting through Black and Mexican-American neighborhoods in East and South Los Angeles, displacing thousands and subjecting those that remained to noise, pollution, and the continued encroachment of industry. On that note, the 1950s and 1960s saw infrastructure projects supporting incredible expansions of port operations at the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, helped along by expanded goods movement corridors, that have contributed to cancer risk, pregnancy complications, and respiratory illness for many decades. Sticking to the Los Angeles area, the Battle of Chavez Ravine––in which the City of Los Angeles forcefully evicted the Mexican-American communities in Chavez Ravine to make way for Dodger Stadium––took place in the 1950s and 1960s, and could surely be classified as a “big thing.”

So why invoke the (often deeply unjust) projects of these decades for a set of overall modest reforms to CEQA? It could be because most agree that larger CEQA and permitting reforms are on the horizon and Governor Newsom is setting the stage for a much messier battle.

California is in the midst of a housing crisis; it’s facing a backlog of energy and infrastructure projects to meet its climate goals; and it’s looking to capitalize quickly on federal infrastructure dollars being awarded to states under the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and the CHIPS Act. In Sacramento, there’s been a stream of successful legislative proposals ostensibly designed to streamline CEQA review for both market rate and affordable housing; and the Little Hoover Commission (an independent, bipartisan state oversight agency) recently held its fifth hearing considering recommendations on potentially broad legislative reforms to CEQA, during which critics and supporters of CEQA went back and forth on CEQA’s role in the housing crisis, decarbonization, equitable building policy, transportation, and so on. (Thoughtful and informative written testimony was also submitted by law professors/Legal Planet contributors Richard Frank, Eric Biber, and former UCLA Law professor Sean Hecht).

Empirically, there isn’t much to be said that wouldn’t be repeating the same few studies that regularly arise in the CEQA debate. Several studies conclude that CEQA is decidedly not a primary driver of California’s housing/infrastructure backlogs and that political barriers, labor and materials costs, and exclusionary zoning are the real culprits. Perennial CEQA-haters Holland & Knight put out seemingly annual studies claiming the opposite (which, as has been pointed out here in the past, rely on dubious data and methodology).

Environmental justice groups have every reason to be concerned by the growing cottage industry of anti-CEQA commentators. Rhetorically, the dialogue connecting housing, infrastructure, and CEQA is driven by a neoliberal/libertarian hybrid of shallow supply-and-demand economics. In this growing movement, any multi-family housing development is an unquestioned good and anything that may stop or slow development is necessarily a cudgel wielded by NIMBYs. (I’m also skeptical that giving developers carte blanche to build market-rate housing will do much, if anything, to relieve competition for deeply affordable housing unless it’s paired with very strong affordability set-asides and anti-displacement measures, but that’s best saved for another post).

Although it’s possible that NIMBYism (particularly in wealthy, majority-white communities) contributes in some way to California’s affordable housing shortage or infrastructure troubles, CEQA is not the primary or only tool used to oppose these projects. And pointing fingers at CEQA––which I see regularly in terrible op-eds and Twitter takes, but also in policy forums like Little Hoover––often deeply discounts CEQA’s value and necessity to environmental justice communities. CEQA is frequently the only tool that allows fenceline communities to make their voices heard during the project planning process. It serves the dual purposes of informing the public and decisionmakers of the environmental impacts related to a project, and of requiring agencies to mitigate those environmental impacts to the extent feasible. CEQA is fundamental to the principals of environmental justice, which emphasize stepping back and allowing overburdened communities to speak for themselves and promote community-led planning processes.

Julia pointed out in a post last year (another response to Klein, coincidentally) that those who point the finger at CEQA often frame infrastructure-related injustice as an artifact of the past, akin to racial covenants. They argue that this injustice is why the Legislature passed CEQA in the first place. But now, California has the admirable goals of promoting decarbonization and mass public transit, addressing water scarcity, and building dense housing. And California should be expediting projects that further these goals, not smothering them in environmental review and potential litigation. But having spent my first job out of law school working for a community-led environmental justice organization in Huntington Park and Wilmington, I can say unequivocally that harmful and discriminatory project proposals are still around, and housing and schools are still being proposed on contaminated and toxic land. Likewise, even today’s “green” infrastructure projects still risk turning overburdened communities into sacrifice zones. It’s tough to point to a more apt example of this than Ford’s $5.6 billion electric truck plant construction project, for which Tennessee used eminent domain to seize land from a group of Black farmers, allegedly for a fraction of its value.

So, to the extent that Governor Newsom’s lofty references to California’s ‘50s and ‘60s and his comparatively modest CEQA bills are a stalking horse for larger CEQA reform, environmental justice groups are wise to draw a line in the sand here and now.

Credit: Tony Barnard, Los Angeles Times (CC BY 4.0)

Credit: Tony Barnard, Los Angeles Times (CC BY 4.0)The post Governor Newsom’s CEQA Bills Could Be a Modest Step in the Wrong Direction appeared first on Legal Planet.