Principles #4 and #5 for Fostering Civic Engagement Through Digital Technologies: Engage On-line and Off-line, and Prepare for the Future

Freedom to Tinker 2013-04-22

As part of my continuing series, today I’ll discuss two more principles for fostering civic engagement and digital technologies. My earlier posts are: #1 Know Your Community #2 Keep it Simple #3 Leverage Entrepreneurial Intermediaries

Principle #4: Utilize Creative Combinations of On-line and Off-line Communications

Whether it’s a grass roots organization, national political campaign or local government agency, any group that wishes to identify and motivate people to become involved in civic affairs needs to use creative combinations of on-line and off-line communications. In today’s post, I will discuss two different situations where I’ve observed people combining new technology and traditional grass roots organizing to foster civic engagement.

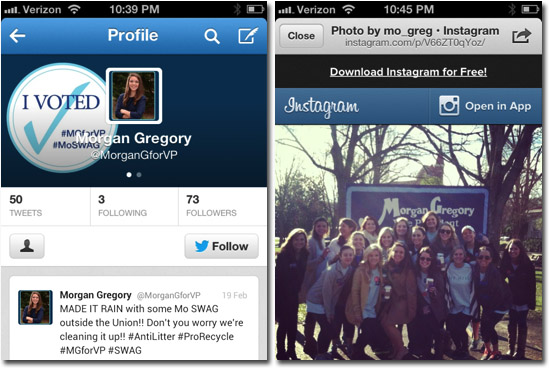

On Twitter, I recently came across an account dedicated to a student’s grass roots campaign for Vice President of the student government at The University of Mississippi (Ole Miss). Her tweets below are a simple representation of today’s hybrid on-line/off-line grass roots campaign.

Notably, Ms. Morgan decided that a Twitter account was a useful part of her campaign communications strategy. She uses Twitter not only to highlight some of her campaign themes (pro-recycling & anti-litter) and slogan (Mo SWAG), but also to organize her supporters off-line. One of her tweets tells people where she and her supporters are gathered (outside the Union). The tweet in the middle is of a photo from Instagram, showing a picture of her supporters in front of a giant campaign billboard, presumably located somewhere on campus. Ms. Morgan rightfully figured that the billboard was great for name recognition, but might be enough to keep people engaged during the campaign. In addition, she probably also knew that having 73 Twitter followers for her campaign account was probably not enough to win the election on a campus with approximately 15,000 undergrads. Ms. Morgan also needed the grass roots support evidenced by a group of friends gathered in front of her sign. And yes, Ms. Morgan did win the election.

In my experience in Washington, DC, Advisory Neighborhood Commissions, the most grass roots level of City government, are adopting similar hybrid approaches. Driving near my house, I have seen campaign-style yard signs on the side of the road advertising one Commission’s monthly meeting. I have also received e-mail notifications and text messages alerting me of local civic gatherings and where to find a full list of the dates and times for meetings in my neighborhood on-line. At South by Southwest this March, on the topic of using social media, Newark Mayor Corey Booker said:

“The tools of our parents worked so well with media–They mastered it and organized. We’re not mastering those tools. We have better tools than they had. We can create values in places that our parents couldn’t even imagine.”

I agree and think that adapting the tools to the times is an exciting challenge that will lead to unique solutions tailored to different communities.

One of the new digital tools is civic games. Eric Gordon, currently a Fellow at the Berkman Center, has developed a series of digital role playing games that people in several communities have used, re-empowering citizens in those communities to contribute to solving local problems in new ways and, as a byproduct, bringing the traditional community meeting into the 21st Century. For example, Participatory Chinatown was a role playing game in which people gathered in a room and played an on-line game in which they walked their avatar around Boston’s Chinatown, solving problems particular to their character. More recently, Mr. Gordon developed his Community PlanIT game platform, in which players answer questions and complete challenges to earn coins, which players can pledge to a variety of causes. The top three causes to which people pledge money on-line receive actual cash awards at the end of the process. With Community PlanIT, people do not need to meet in person to participate, but do get to know each other through their on-line avatars, which include players’ actual first names. Mr. Gordon has used this platform to facilitate community engagement in solving problems related to the Boston’s Public Schools, Detroit’s Master Plan, and urban planning in neighborhoods in Southwest Philadelphia.

One of the new digital tools is civic games. Eric Gordon, currently a Fellow at the Berkman Center, has developed a series of digital role playing games that people in several communities have used, re-empowering citizens in those communities to contribute to solving local problems in new ways and, as a byproduct, bringing the traditional community meeting into the 21st Century. For example, Participatory Chinatown was a role playing game in which people gathered in a room and played an on-line game in which they walked their avatar around Boston’s Chinatown, solving problems particular to their character. More recently, Mr. Gordon developed his Community PlanIT game platform, in which players answer questions and complete challenges to earn coins, which players can pledge to a variety of causes. The top three causes to which people pledge money on-line receive actual cash awards at the end of the process. With Community PlanIT, people do not need to meet in person to participate, but do get to know each other through their on-line avatars, which include players’ actual first names. Mr. Gordon has used this platform to facilitate community engagement in solving problems related to the Boston’s Public Schools, Detroit’s Master Plan, and urban planning in neighborhoods in Southwest Philadelphia.

During a recent presentation at the Berkman Center, Mr. Gordon made two excellent points about civic games that I think are also applicable to innovative forms of digital civic engagement more generally. One is that participants have an increased level of trust in the engagement process when the request to participate comes from a community organization or social contact rather than the government. The second issue, which Mr. Gordon is working to address regarding his Community PlanIT platform, is communities continuing to use innovative approaches to problem solving when the person with funding for a research project cannot be there to shepherd the process.

These are critical issues that will determine how quickly civic innovation can happen on a wider scale beyond Boston and other cities with connections to major universities. When will people begin to see the implementation of technology in the traditional neighborhood association or community meeting as the new normal? Who introduces new approaches to civic engagement in a small town or evolves the approaches that have been piloted in Boston? I believe a healthy digital community needs technological resources and ongoing partnerships to facilitate this type of engagement on a continuing basis and will continue to highlight the conditions that enable digital civic innovation in communities across the U.S. in future posts.

Principle #5 Ready Your Community for Today’s and Tomorrow’s Technologies

Local governments need to foster civic engagement through today’s digital technologies and ready their communities to use tomorrow’s technologies for civic purposes. Fostering an environment of experimentation and creativity for both government-owned technology applications and civic-focused entrepreneurs is a great challenge for local communities. With one gigabit per second upload and download speeds available through Google Fiber in Kansas City and wide availability of white space devices on the horizon, local governments need to be thinking about whether there are changes in municipal rules and regulations that will make deployment of fiber easier and enable localities to leverage exceptionally fast speeds to quicken service delivery.

In speaking with experts on fiber deployment and white spaces, I was reminded of one of the differences in problem solving outlooks between government lawyers and private sector engineers. As a lawyer, I asked “how will these new technologies be used by government?” The answers I received reminded me that I needed to broaden my framework — don’t be a person who sees new things and then only tries to organize them into known categories. A smart developer is building the technology to be flexible, yet also sustain over time, allowing users to have their say and potentially discover uses that the original developer had not imagined. Embracing that flexibility is challenging for government because it is difficult for an elected official to tell taxpayers and other stakeholders, “we’re changing rules and spending money to promote the growth of a new technology; we don’t know exactly what it’s going to be used for yet — but it will be better than what we have now.” And yet, it’s very necessary for local governments to do just that.

One case where a local community has embraced this type of effort is the launch of Google Fiber in Kansas City. Actually, both Google and the City embraced changes in the way broadband is typically deployed in order to launch the experiment. Google is using “a Groupon-style business model,” as it was artfully described to me, where once a critical mass of people in a particular neighborhood pre-register for the service, that neighborhood moves to the top of the priority list for build-out. From Google’s perspective, this de-risks the business model, shortcutting some of the concerns that Verizon faced on Wall Street when it began deploying FIOS. Google Fiber’s business model is potentially better than other providers’ models for spurring broadband adoption – and thereby increasing the likelihood of corporate profitability – because it forces Google to try new marketing initiatives, such as opening a physical location, The Google Fiber Space, to show potential customers the benefits of super high-speed Internet.

In winning a competition with more than 1,100 communities to win the Google Fiber deployment, Kansas City showed that it really wanted the project. Kansas City became fiber-ready by smoothing the right-of-way process, allowing Google to dig once in many places, thereby saving time and money. Kansas City’s approach is consistent with the spirit of President Obama’s June 2012 Executive Order, “Accelerating Broadband Infrastructure Deployment,” which required Federal agencies to “revise their procedures, requirements, and policies to include the use of dig once requirements and similar policies to encourage the deployment of broadband infrastructure in conjunction with Federal highway construction…” Many of the appealing uses for gigabit Internet service for businesses and residents also provide excellent opportunities for civic innovators — videoconferencing, connected schools, faster access to government websites and an increased ability to use cloud-based services.

In the mobile wireless landscape, white spaces — the unused spectrum between television stations — provide a new opportunity for experimentation and innovation, including for civic purposes. In particular, white spaces could have significant civic benefits for outdoor connectivity. For example, I was told that as part of a white space trial in India earlier this year, police placed high-resolution cameras on vehicles in an area where people were rioting and used white spaces devices to transmit high-resolution pictures to a central location where police could see who was breaking the law. Given that numerous American cities have crime and traffic cameras, it is easy to imagine similar technology being adopted here. With white spaces’ superior propagation characteristics, images could be transmitted beyond line-of-sight, from an area police are monitoring to a nearby police substation or patrol car just off in the distance. I can also envision white spaces base stations at local schools and libraries, allowing hyper-local broadcasting of a school play, basketball game or neighborhood association meeting. Right now, innovators are still developing white spaces devices in their labs. Over the next two or three years, devices compatible with white spaces spectrum will start coming to market, replacing the current generation of wireless devices used by citizens and government users. It is not difficult to imagine Google Glass — a wearable computer with a head mounted display — relying heavily on the excellent outdoor connectivity available through white spaces spectrum. As you’re looking around, just don’t forget to search for information on the location of local civic association meetings, playgrounds and voting precincts.