Ambiyllabicity

Language Log 2024-12-14

The comments on "Hypertonal conlang" (12/8/2024) include a lengthy back-and-forth about where the syllable break should be located in English words like "Cheryl". I was surprised to see that no one brought up the concept of ambisyllabicity, which has been a standard and well-accepted idea in phonology and phonetics for more than 50 years. It continues to be widely referenced in the scholarly literature — Google Scholar lists about 2,170 papers citing the term, and 260 since 2020.

The most influential source is Dan Kahn's 1976 MIT thesis, “Syllable-based Generalizations in English Phonology”. There's more to say about the 1970s' introduction into formal phonology of structures beyond phoneme strings (or distinctive feature matrices), but that's a topic for another time.

Dan's 1976 thesis introduces the concept on pp. 33-35, under the heading "Section 3 – Ambisyllabicity". You can read the whole thesis here, but for convenience, here's the text of that section:

In all traditional treatments of English syllabication, a word like atlas would consist of two syllables, [at] and [las]. Since each syllable is well-defined, it makes sense to speak of a "syllable boundary" as occurring between the [t] and [1] of atlas. This phenomenon of well-defined boundary is observed in a large class of cases in English, leading to the general assumption on the part of many phonologists that it is always possible to segment an English utterance into n well-defined syllables, i.e., to choose (n-1) intersegmental positions as syllable-boundary locations.

However, this conclusion is not a logical necessity. There need not correspond to every pair of adjacent syllables a well-defined syllable boundary. For example, as opposed to a word like atlas, where the boundary between syllables is uncontroversial, it would seem completely arbitrary to insist that hammer contains a syllable boundary either before or after the [m].

In the past this fact has been typically either ignored (but see below), in which case one arbitrarily assigns a syllable boundary in a word like hammer, or else taken as evidence that the concept of the syllable is an untenable one. The position taken here is a middle one between these two extremes: it makes sense to speak of hammer as consisting of two syllables even though there is no neat break in the segment string that will serve to define independent first and second syllables.

Using Pike's term "sonority" (each syllable contains exactly one "peak of sonority"), there appears to be a sonority trough at the [m] in hammer, as opposed to a complete break in sonority between the [t] and (1] of atlas. It would seem reasonable to maintain, then, that while hammer is bisyllabic, there is no internal syllable boundary associated with the word. As an analogy to this view of syllabic structure, one might consider mountain ranges; the claim that a given range consists of, say, five mountains loses none of its validity on the basis of one's inability to say where one mountain ends and the next begins.

The observation that polysyllabic words in English need not have well-defined syllable boundaries has in fact been made before. Careful phoneticians not committed to a theory of well-defined syllabication have suggested that intervocalic consonants in English may belong simultaneously to a preceding and a following vowel's syllable.

For example, in discussing words like being, booing, Trager & Smith (1941:233) say, "…in cases like these, the intersyllabic glide is ambisyllabic (i.e., forms phonetically the end of the first and the beginning of the second syllable), so that these words exhibit a syllabic structure exactly parallel to that of such words as bidding…"

Smalley (1968:154) points out that it is easy to identify the "crests" of syllables but notes that "it is not always possible to determine an exact syllable boundary. A consonant between two syllables may belong phonetically to both." He gives the English word money as an example of this phenomenon.

The difficulty speakers of English experience in saying, in many cases, just where one syllable ends and the next begins, referred to by Abercrombie (see quote above), is doubtless due to their uncertainty about arbitrary syllabication conventions in these ambisyllabic cases. The only phonologists who to my knowledge try to deal formally with the phenomenon of ambisyllabicity in English are Anderson & Jones (1974). For them also, words like hammer, being, booing, bidding, and money would involve ambisyllabic segments. I will have more to say about their proposals below and in Chapter II.

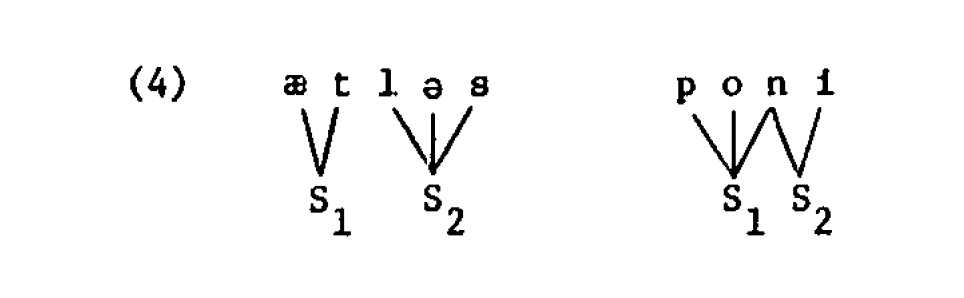

One reason that Dan's work was so effective was the notation he suggested. Here's his Figure 4, illustrating the syllable structure of atlas and pony:

His ideas was to treat syllables as "suprasegmental" or "autosegmental" entities, analogous to tones, listed on a separate tier and connected to the segmental sequence by links that obey order allow segments to be shared by two adjacent syllables.

There have been many additional ideas about syllabic (and sub-syllabic and super-syllabic) structure, the relationship of those structures to phonological features, and the place of the traditional concept of "segment" in all that. But essentially all of these proposals agree on the idea that there are some phonological entities (whether segments or features or whatever) that belong to two adjacent syllables (or syllable-like entities).

Update — the earlier works cited in the quoted section from Kahn 1976 include:

Trager & Smith, "An Outline of English Structure", 1957. Smalley, "Manual of Articulatory Phonetics", 1963. Anderson & Jones, "Three theses concerning phonological representations", 1974.