Hu Shih and God: thearchs across Eurasia

Language Log 2024-12-28

Dr. Hu Shih (1891-1962) was arguably the greatest Chinese scholar of the 20th century, for whom I have the utmost respect. He and I thought alike on a number of important subjects: language, literature, and script reform, philosophy (we both were attracted to the utilitarian-pragmatist-logician and defensive strategist Mo Zi [c. 470 -c.391 BC]), recognition of the great influence of Indian civilization upon Chinese culture, dedication to public service and education, devotion to democracy, and so forth. Overall, the only other 20th-century thinker and writer who could compete / compare with Hu Shih was Lu Xun (1881-1936), but the latter came from the left, whereas Hu Shih came from the right. I admired them both.

Even when I was a child, I was never a theist, and I stopped going to church when I went to college and my mother wasn't around to urge me to do so. Likewise, I suspected that Hu Shih, being a Confucian minded Chinese intellectual, was not a theist either. So it was quite a surprise when the following notice from the Hu Shih Memorial Hall in Taipei came to my attention:

Here is a slightly modified Google Translation:

[The Chinese translation of GOD]

Hu Shi spent his lunar birthday in National Taiwan University Hospital on December 24, 1961. Since it happened to be Christmas Eve, a Christmas tree was also decorated in the ward to commemorate the occasion. Therefore, Hu Shi talked about the problem of the Chinese translation of "GOD" after the introduction of Catholicism, which involved the rank of the eight gods in a Shandong Ritual Temple. In addition, after Hu Shi analyzed the names for the core of faith around the world, he believed that there seemed to be some involvement in seemingly unrelated fields. "Mr. Hu Shizhi's Conversations in His Later Years" is compiled as follows:

Today is the 17th day of the 11th month on the lunar calendar. It is Hu Shi’s birthday and it is also Christmas.

Hu Shi put on the brocade dressing gown that a dozen people including Qian Siliang had given him a while before, and sat on the bed reading the newspaper. When Hu Songping arrived at the ward, he congratulated Hu Shi, who raised his hands and kindly and cheerfully bowed in return. At this time, the small colored electric lights on the Christmas tree in the room flickered on and off, reflecting various decorations, making it particularly lively. Hu Shi said: "This is probably because I am a heathen. Some of the head nurses used to make it look very beautiful. (heathen means people other than Christians)"

Hu Shi said: "Jehovah was originally an ancestral protective spirit of the Jewish nation. Jesus was a Jew, so Jehovah became a god commonly respected by Christians all over the world. The Jewish nation had been subjugated for more than a thousand years, relying entirely on religious strength to keep their nation together, and now it has reestablished itself as a country. Jewish culture has conquered almost half of the world. At first, the people who came to China to preach Christianity were all learned, and they were all Jesuits who translated the name of this supreme deity as "Lord of Heaven" (Tiānzhǔ 天主). Later, the Benedictines came. According to the Historical Records, "Book of Sacrifice to Heaven and Earth", the eight gods of Qin Shihuang*'s (259-210 BC) temple for ritual sacrifice in Shandong were the Lord of Heaven, the Lord of Earth, the Lord of War, the Lord of Yin, the Lord of Yang, the Lord of Moon, and the Lord of Sun, plus the Lord of the Four Seasons The Benedictines believed that if the Jesuits would lower the translation of the highest Christian "God" to be the same name as one of the eight gods in Shandong, wouldn't this be an insult to Jehovah? The case went on for a long time, and the lawsuit went to the Pope. So in the future, the missionaries changed their name to "Lord" and said just "Lord" when praying. They initially called God "Lord of Heaven" and then "Thearch Above" (Shàngdì 上帝), which seems to be due to Protestant influence. I'll check it out when I get back to Nangang**." The teacher added: "The original meaning of the word 『dì 帝』 ("emperor; thearch") was "spirit; god". In the early part of the Yin / Shang Dynasty (ca. 1600-1046 BC), the names of emperors were chosen after the heavenly stems and earthly branches of their birthdays, but those who possessed special merit for their ancestors had the word 『dì 帝』("thearch") added before their name to indicate special respect, e.g., "Dì yǐ 『帝乙』". It was not until Qin Shihuang ("First Emperor of the Qin") that he called himself the First August Thearch (shǐ huángdì 始皇帝). In the past, he would not have dared to use the word 『dì 帝』 ("thearch") for himself. I often think about the meaning of the Chinese word 『dì 帝』 ("thearch") , and the Sanskrit word "deva", the Latin word "deus", and the Greek word "zeus". The pronunciation and meaning are the same, as if they come from the same origin."

File description: On November 26, 1961, Hu Shi was admitted to National Taiwan University Hospital due to heart discomfort and was not discharged from the hospital until January 10 of the following year. The picture shows Hu Shi in the Special Ward No. 1 of National Taiwan University Hospital in December 1961.

Reproduction location: Showroom of Hu Shi Memorial Hall

—

*First Emperor of the Qin / Ch'in (whence the country name "China" is derived), the first Chinese emperor to call himself huángdì 皇帝 ("August Thearch")

**Nangang is outside Taipei, where Hu Shih was living at Academia Sinica.

Because the text is so long, and few people who are not fluent speakers will want to read the romanized text, I omit it here.

There are a lot of fine theological points in this text that not even Hu Shih could straighten out off the top of his head, so don't expect what is written here to be definitive. One thing is certain, however, those who came to see Hu Shih in the hospital and those responsible for writing this note held him in the highest esteem. They respectfully refer to him with the Sino-Japanese honorific 先生 (J. sensei / Hok.siăn-sé / MSM xiānshēng), which machine translators often render as "husband", whereas in this context it means something more like "Sir", "Mister", "teacher", "doctor", etc.,

As further indication of my mental and spiritual affinity with Hu Shih, what he says about 『dì帝』 ("thearch; emperor") has a remarkable resonance with what I've been saying and writing for half a century. Here is one fairly extensive presentation of the idea, though I had entertained these thoughts (the congruity, as Hu Shih opined, of『dì 帝』 and Sanskrit "deva", Latin "deus", and Greek "zeus", already when I was in graduate school, though my list embraced Middle Eastern and Central Asian congeners as well.

These two lengthy paragraphs are from Victor H. Mair, "Religious Formations and Intercultural Contacts in Early China", in Volkhard Krech and Marion Steinicke, eds., Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe: Encounters, Notions, and Comparative Perspectives. Series: Dynamics in the History of Religions, Volume: 1 (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 85-110; pp. 97-98, n. 26:

Counting the time for preparation and publication, all of this was happening 15 or more years ago. It was beginning to feel like ancient history, but then comes this unexpected blast from the past delivered by none other than Hu Shih, one of my leading paragons for the past 56 years.

Addenda

If you have a suitable browser, you can view that cuneiform glyph here: (U+1202D : CUNEIFORM SIGN AN)

Historical forms of 帝 are available here in Wiktionary.

Julie Wei has authored many issues of Sino-Platonic Papers (SPP) — 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166 suppl. (all September-November, 2005), and 324 (March, 2022) — that take into account these ideas about Sumerian dingir and Sinitic 『dì帝』and related questions. (All issues of SPP are easily available online as free PDFs at https://sino-platonic.org/). Wei has also compiled a document in which she includes the following phonological, etymological, and graphological data concerning 帝:

帝 *tigh (Li Fang-kuei, in Schuessler, A Dictionary of Early Zhou Chinese, p. 123),

*tikh “a god, divine king, deceased king, ‘emperor’ ” (Schuessler, in Schuesler, A Dict. Of Early Zhou Chinese, p 123),

*tekh “god, ancestor, honorific for deceased fathers” (Schuessler, in Schuessler, Etymological Dict. of Old Chinese, 2007, p.210),

Schuessler on etymology: Sino-Tibetan: Written Tibetan: the “celestial gods” of the Bon religion.

*teegs , Zhengzhang Shangfang 郑张尚芳, Old Chinese Phonology 上古音系, 2003 , p. 303.

Wiktionary 帝

Etymology

From Proto-Sino-Tibetan *teɣ (“God”); compare Tibetan ཐེ (the, “celestial gods of the Bon religion”), Jingpho [script needed] (mə³¹-tai³³, “god of the sky”), Proto-Bodo-Garo *mɯ-Dai⁴ (“spirit; god”) (Coblin, 1986; Schuessler, 2007; Sagart, 2011). Cognate with 禘(OC *deːɡs, “a kind of sacrifice”) (Schuessler, 2007).

Alternatively, Sagart (1999) derives it from a root *tek (“to be master over; to rule over”), whence also 適 (OC *ᵃtek, “to rule; to control”), 嫡 (OC *ᵃtek, “son of principal wife”).

___________________

Wiktionary:

Sanskrit द्युक्ष • (dyukṣá) stem(Vedic) “celestial, heavenly, shining, brilliant”

Etymology

Inherited from Proto-Indo-Aryan *dyukṣás, from Proto-Indo-Iranian *dyukšás, from Proto-Indo-European *dyutkós (“celestial, heavenly”), from *dyew- (“to be bright; sky; heaven”).

*dewo- “god” , Proto-Celtic, in Ranko Matasovic, Etymological of Proto-Celtic, 2009, p. 96.

Pronunciation

Adjective

द्युक्ष • (dyukṣá) stem(Vedic)

Declension

Masculine a-stem declension of द्युक्ष (dyukṣá)Feminine ā-stem declension of द्युक्षा (dyukṣā́)Neuter a-stem declension of द्युक्ष (dyukṣá)References

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1890) “द्युक्षः”, in The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary, Poona: Prasad Prakashan

- Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1893) “द्युक्ष”, in A practical Sanskrit dictionary with transliteration, accentuation, and etymological analysis throughout, London: Oxford University Press

- Monier Williams (1899) “द्युक्ष”, in A Sanskrit–English Dictionary, […], new edition, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, →OCLC, page 499.

Also from Julie:

Below is the Sumerian DIĜIR/DINGIR sign from Wikipedia "Dingir".

Cuneiform sign

Sumerian

The Sumerian sign DIĜIR ⟨⟩ originated as a star-shaped ideogram indicating a god in general, or the Sumerian god Anu, the supreme father of the gods. Dingir also meant 'sky' or 'heaven', in contrast with ki which meant 'earth'. Its emesal pronunciation was dimer. (The use of m instead of ĝ [ŋ] was a typical phonological feature in emesal dialect.)

The plural of diĝir can be diĝir-diĝir, among others.

Assyrian

The Assyrian sign DIĜIR (ASH ⟨⟩ and MAŠ ⟨⟩, see could mean:

- the Akkadian nominal stem il- meaning 'god' or 'goddess', derived from the Semitic ʾil-

- the god Anum (An)

- the Akkadian word šamû, meaning 'sky'

- the syllables an and il (from the Akkadian word god: An or Il, or from gods with these names)

- a preposition meaning "at" or "to"

- a determinative indicating that the following word is the name of a god

According to one interpretation, DINGIR could also refer to a priest or priestess although there are other Akkadian words ēnuand ēntu that are also translated priest and priestess. For example, nin-dingir (lady divine) meant a priestess who received foodstuffs at the temple of Enki in the city of Eridu.[4]

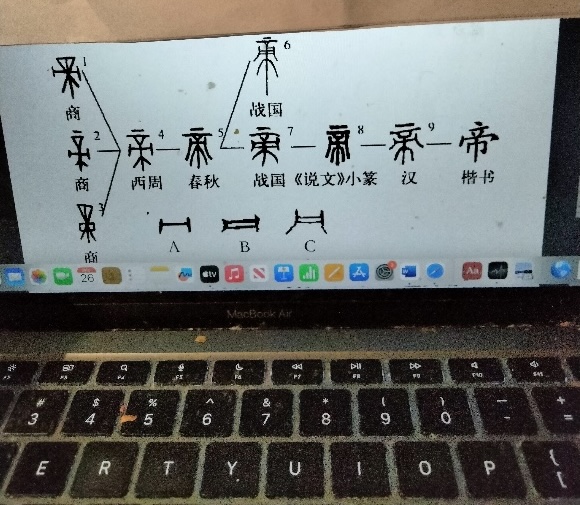

Below is Oracle Bone character 帝 from Baidu Baike "帝“.

Julie Wei is still preparing additional materials for future publications on these questions.

Selected readings

- "Some Old Chinese terms relating to religion, mythology, ritual" (9/17/23) — vital post by Axel Schuessler, with extensive discussion in the comments by Chris Button and others

- "Thai 'khwan' ('soul') and Old Sinitic reconstructions" (2/28/19) — another energetic, high-level discussion in the comments

- "Script origin and typology, part 2" (7/5/24) — see especially this comment by Chris Button

- "Old Chinese onsets and the calendrical signs" (1/12/23)

[Thanks to shaing tai]