The cost of commas?

Language Log 2025-01-05

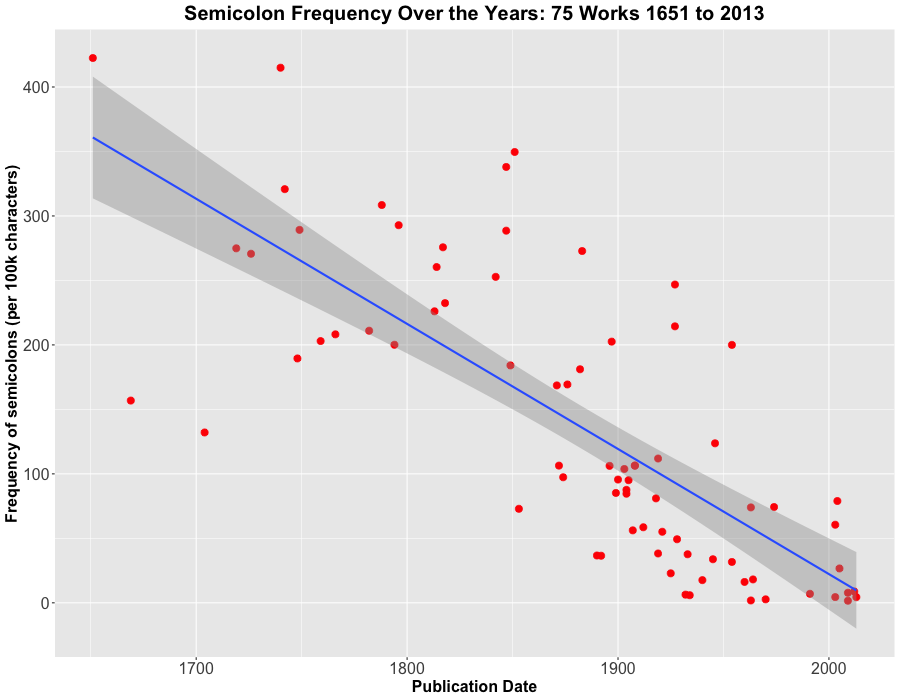

My 1/2/2025 post "American health care in 1754" quoted at length from Benjamin Franklin's account of the founding of Pennsylvania Hospital. The main point was the striking difference between then and now in the attitudes of (some) business leaders. But since this is Language Log rather than Health Care Politics Log, I suggested "the obvious stylistic change in sentence length" as a linguistic angle, with a link to the slides for my presentation at SHEL12 in 2022, "Historical trends in English sentence length and syntactic complexity". And Julian reponded in the comments: "Clearly commas were cheaper, in those days". Punctuation is definitely part of the picture — especially semicolons, as this figure from my 2022 presentation illustrates:

But commas, not so much. It's plausible that longer sentences also tend to use more commas, but I didn't bother to check for that. I could redo the 75-work semicolon analysis to count commas, and maybe I'll do that later if there's interest, but for now, here's a illustrative comparison between Franklin's 1754 publication and David Lodge's 1984 Small World:

TitleSemicolons per 100k charsCommas per 100k charsFranklin 1754145.3186.5Small World1.677138.3Franklin's 145.3/100k semicolon rate (=1.453%) is on the low side for the middle of the 18th century, at least according to the graph above. But it's still more than 86 times David Lodge's 1.677 /100k (=0.01677%) rate (145.3/1.677 =86.64).

In contrast, Franklin's 186.5/100k comma rate (=1.865%) is only about 35% greater than David Lodge's rate of 138.3/100k (=1.383%) — 186.5/138.3 = 1.345.

There's some relevant discussion in "Death before syntax?", 10/20/2014.

And as a final note, it's worth thinking about whether there's an genuine analogy to the economic effects of pricing/supply/demand/etc., as suggested by Julian's metaphor. The typographical cost of semicolons and commas doesn't change, and there's no obvious sense in which the supply changes, though maybe we can think of cultural patterns as a kind of supply variable? But the desire for longer and more "periodic" sentences arguably increases the demand, I guess.