Comma/Period ratios

Language Log 2025-01-06

In the discussion of "The cost of commas", RfP wrote "I would be interested in seeing figures for the difference in the relative use of periods between Franklin and Lodge, in relation to the use of commas and semicolons".

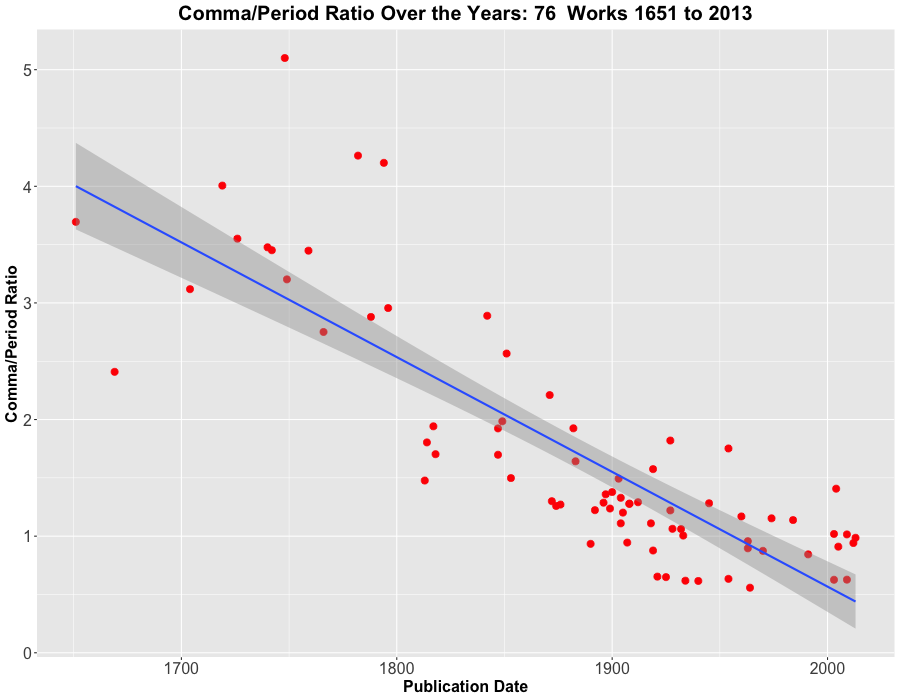

It's obvious that the secular trend in English towards shorter sentences will tend to reduce the frequency of periods, at least in the case of works where commas and periods are rarely used as part of numbers and similar non-phrasal symbols. And therefore the frequency of commas relative to periods should decrease, even though the overall frequency of commas doesn't change a great deal. Unsurprisingly, that's what we see:

Something emerged from the analysis that did seem interesting to me, namely the fact that the two lowest comma/period ratios in the set of texts that I checked were the two Hemingway works in the list, A Moveable Feast (ratio 0.558) and For Whom the Bell Tolls (ratio 0.616).

This might be what we should expect, given the (false) stereotype that Ernest Hemingway's writing is a sequence of short, simple sentences.

More than one smart person has bought into this idea. As I noted in "Homo hemingwayensis" (1/9/2005), a piece by James Thurber entitled 'A Visit from Saint Nicholas (In the Ernest Hemingway Manner)', in the 12/24/1927 edition of the New Yorker, starts like this:

It was the night before Christmas. The house was very quiet. No creatures were stirring in the house. There weren’t even any mice stirring. The stockings had been hung carefully by the chimney. The children hoped that Saint Nicholas would come and fill them.

The children were in their beds. Their beds were in the room next to ours. Mamma and I were in our beds. Mamma wore a kerchief. I had my cap on. I could hear the children moving. We didn’t move. We wanted the children to think we were asleep.

The whole satirical passage has 104 sentences with a mean length of 6.96 words, which certainly fits the stereotype.

And in Death before syntax?" (10/20/2014) I quoted Ursula K. LeGuin, in her essay "Introducing myself":

What it comes down to, I guess, is that I am just not manly. Like Ernest Hemingway was manly. The beard and the guns and the wives and the little short sentences. I do try. I have this sort of beardoid thing that keeps trying to grow, nine or ten hairs on my chin, sometimes even more; but what do I do with the hairs? I tweak them out. Would a man do that? Men don’t tweak. Men shave. Anyhow white men shave, being hairy, and I have even less choice about being white or not than I do about being a man or not. I am white whether I like being white or not. The doctors can do nothing for me. But I do my best not to be white, I guess, under the circumstances, since I don’t shave. I tweak. But it doesn’t mean anything because I don’t really have a real beard that amounts to anything. And I don’t have a gun and I don’t have even one wife and my sentences tend to go on and on and on, with all this syntax in them. Ernest Hemingway would have died rather than have syntax.

But in fact Hemingway's sentences are on average roughly twice as long as LeGuin's, as I pointed out in that same post:

The first 554 words of Ursula K. LeGuin's wonderful novel The Dispossessed contain 39 sentences, for an average length of 14.2 words per sentence. The first 572 words of Ernest Hemingway's justly famous novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (excluding dialogue) contain 20 sentences, for an average length of 28.6 words per sentence.

The first 759 words of Ursula K. LeGuin's essay "Introducing Myself" contain 51 sentences, for an average length of 14.9 words per sentence. The first 786 words of Ernest Hemingway's essay "Miss Stein Instructs" contain 31 sentences, for an average length of 25.4 words per sentence.

The 598 words of Ursula K. LeGuin's essay "Being Taken for Granite" contain 46 sentences, for an average of 13 words per sentence. The first 764 words of The Old Man and the Sea (excluding dialogue) contain 28 sentences, for an average of 27.3 words per sentence.

And again, compare Thurber's Hemingway satire with an average sentence length of 6.96 words.

In "Lexical display rates in novels" (4/18/2020), I suggested that part of the explanation for this (apparently false) stereotype might be the fact that Hemingway's rate of lexical display is lower than any other novelist I've tested, e.g. compared to Thomas Pynchon:

Now I wonder whether Hemingway's sparse use of commas might also be part of the story. For a sense of how he deploys punctuation, here's the start of For Whom the Bell Tolls:

He lay flat on the brown, pine-needled floor of the forest, his chin on his folded arms, and high overhead the wind blew in the tops of the pine trees. The mountainside sloped gently where he lay; but below it was steep and he could see the dark of the oiled road winding through the pass. There was a stream alongside the road and far down the pass he saw a mill beside the stream and the falling water of the dam, white in the summer sunlight.

"Is that the mill?" he asked.

"Yes."

"I do not remember it."

"It was built since you were here. The old mill is farther down; much below the pass."

He spread the photostated military map out on the forest floor and looked at it carefully. The old man looked over his shoulder. He was a short and solid old man in a black peasant's smock and gray iron-stiff trousers and he wore rope-soled shoes. He was breathing heavily from the climb and his hand rested on one of the two heavy packs they had been carrying.

That passage has 12 periods and 4 commas.

Getting back to RfP's specific question, Benjamin Franklin's 1754 story of the founding of Pennsylvania Hospital has 174 periods in 65347 total characters, whereas David Lodge's novel 1984 novel Small World has 8979 periods in 739022 total characters.

(8979/739022)/(174/65457) = 4.57

So Lodge used periods about four and a half times as often as Franklin, FWIW.

Update — Reading Gertrude Stein on commas may help understand how Hemingway felt about them:

And now what does a comma do and what has it to do and why do I feel as I do about them. What does a comma do. I have refused them so often and left the out so much and did without them so continually that I have come finally to be indifferent to them. I do not now care whether you put them in or not but for a long time I felt very definitely about them and would have nothing to do with them. As I say commas are servile and they have no life of their own,and their use is not a use, it is a way of replacing one’s own interest and I do decidedly like to like my own interest my own interest in what I am doing. A comma by helping you along holding your coat for you and putting on your shoes keeps you from living your life as actively as you should lead it and to me for many years and I still do feel that way about it only now I do not pay as much attention to them, the use of them was positively degrading. Let me tell you what I feel and what I mean and what I felt and what I meant.

When I was writing those long sentences of The Making of Americans, verbs active present verbs with long dependent adverbial clauses became a passion with me. I have told you that I recognize verbs and adverbs aided by prepositions and conjunctions with pronouns as possessing the whole of the active life of writing. Complications make eventually for simplicity and therefore I have always liked dependent adverbial clauses. I have like dependent adverbial clauses because of their variety of dependence and independence. You can see how loving the intensity of complication of these things that commas would be degrading. Why if you want the pleasure of concentrating on the final simplicity of excessive complication would you want any artificial aid to bring about that simplicity. Do you see now why I feel about that simplicity. Do you see now why I feel about the comma as I did and as I do. Think about anything you really like to do and you will see what I mean. When it gets really difficult you want to disentangle rather than to cut the knot, at least of anybody feels who is working with any thread, so anybody feels who is working with any tool so anybody feels who is writing any sentence or reading it after it has been written. And what does a comma do, a comma does nothing but make easy a thing that if you like it enough is easy enough without the comma. A long complicated sentence should force itself upon you, make you know yourself knowing it and the comma, well at the most a comma is a poor period that lets you stop and take a breath but if you want to take a breath you ought to know yourself that you want to take a breath. It is not like stopping altogether has something to do with going on, but taking a breath well you are always taking a breath and why emphasize one breath rather than another breath. Anyway that is the way I felt about it and I felt that about it very very strongly. And so I almost never used a comma. The longer, the more complicated the sentence the greater the number of the same kinds of words I had following one after another, the more the very more I had of them the more I felt the passionate need of their taking care of themselves by themselves and not helping them, and thereby enfeebling them by putting in a comma.