"You will want to __"

Language Log 2025-06-09

Email from a reader:

In the last several years, when receiving instructive information from gen Z in places of business, I have noticed a regular use of the FUTURE tense, when the present would perfectly suffice. Sometimes, but not always, this is combined with telling me what I WILL WANT to do. To wit,

– "you WILL WANT TO ____" – "the beverages WILL BE on the back of the menu"

There is nothing "wrong" grammatically or logically with any of this (as if there could be). It is perfectly accurate and cromulent. But these forms are relatively new, I conjecture. Even a little jarring.

I can posit my own hypotheses regarding how and why these usages increased in prevalence in recent tears. Is there a literature on it, perhaps already covered by Language Log?

I should start by noting that some people object to calling the English word will a marker of "future tense" — see e.g. Rodney Huddleston's (I think convincing) article "The case against a future tense in English", Studies in Language 1995. Use of will often involves a hypothetical future time reference, as I think it does in examples like those in the email, but the asserted proposition is (often) also true at the time of speaking or reading, wherefore the will is (often) optional.

However, I'm skeptical of the idea that such usage is a Gen Z innovation, since similar things have been around for centuries.

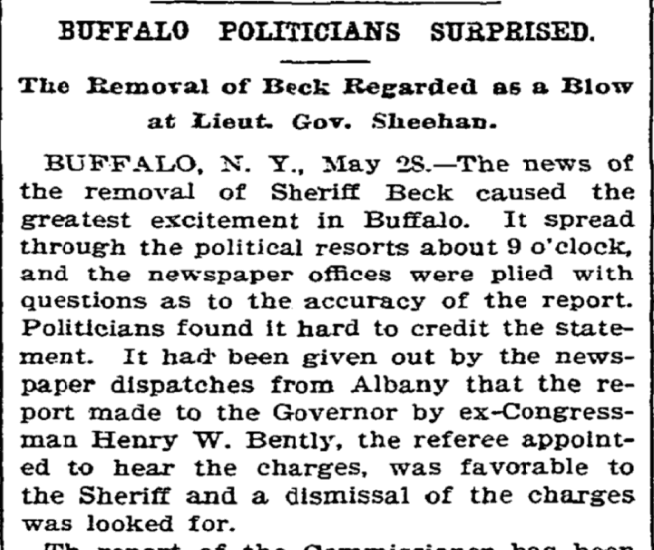

For example, an article published in the NYT on 5/28/1894, under the headline "Buffalo Politicians Surprised", starts this way:

…and ends like this, informing readers that the relevant background "will be found on page 9":

That story was in fact found on page 9 of that edition, so it would also have been appropriate to write that "The story of Sheriff Beck's removal is found on Page 9". The force of the modal "will" is to imply something like "If you care to look…" — it's not a prediction about the future as of May 1894.

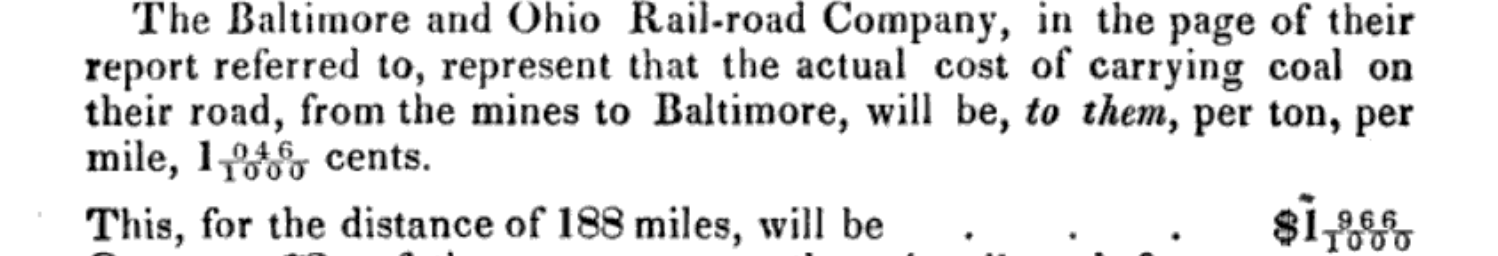

And an 1846 Report on the Present State of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal tells us that the "The Baltimore and Ohio Rail-road Company, in the page of their report referred to, represent that actual cost of carrying coal on their road from the mines to Baltimore, will be, to them, per ton, per mile, 1 046/1000 cents", so that "This, for the distance of 188 miles, will be $1 966/1000":

These hypothetical costs are presented as an estimate of the actual costs as of 1846, if anyone cared to arrange such a shipment, so that "will be" could logically have been replaced by "is".

I don't know of any discussion of this particular question in the scholarly literature, beyond what's implied in papers like Huddleston's.

Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Usage has nothing but a few pages on shall vs. will. But there's quite a bit of relevant stuff in the English usage internet, e.g. "What does 'you will want to' mean?", or "You will want vs. you want", or "'You'll find that…'".

Even though things like this have been around in English for a long time, it still could be true that Gen Z people (those born between 1997 and 2012) use them more frequently, in general or in certain contexts. But this isn't something that I've noticed, and I'm not sure how to check it.