Morphosyntactic variation: Hamlet, Gertrude, Marshall, Bachmann

Language Log 2013-04-30

Over the past few days, I've come across two attempts at antique English verb inflection in a modern political context. One of them is from Josh Marshall, "Godzilla vs. Mothra", TPM 4/29/2013:

This is wild. Bilious WaPo blogger Jennifer Rubin lashes out at “jerk” Sen. Ted Cruz, says he must apologize to GOP colleagues.

And the popcorn shall passeth.

And the other is from Michele Bachmann, as described by Matt Wilstein, "Michele Bachmann Tries, Fails To Quote Shakespeare During House Debate…", Mediaite 4/26/2013:

Bachmann singled out House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Rep. Steny Hoyer (D-MD) for being “extremely passionate” about losses to programs like Head Start and others that benefit children under sequestration when it was President Obama who signed the sequestration bill, and may have even thought it up. “There were numerous Republicans that voted against the sequestration because we knew all of these calamities were in the future. And so it reminds me of the Shakespeare line: ‘Thou protestest too much.’”

So what's with the -eth and the -est? In the OED's discussion of "Grammar in Early Modern English", Edmund Weiner explains:

The second person singular inflection -est naturally declined in importance as the use of thou declined, giving rise to the current arrangement whereby in the present tense only the third singular is marked and all other persons take the base form.

At the start of the period, the normal third person singular ending in standard southern English was -eth. The form -(e)s, originally from Northern dialect, replaced -eth in most kinds of use during the seventeenth century. A few common short forms, chiefly doth, hath, continued often to be written, but it seems likely that these were merely graphic conventions.

Josh Marshall's (no doubt satirical) "passeth" is morphologically wrong, since -eth would only ever have been used in an inflected present tense form of the verb, not in construction with a modal like shall, where the base form would always have been used. Thus in the King James version of the bible, there are 44 instances of "passeth", all of them inflected present tense forms, e.g.

Man is like to vanity: his dayes are as a shadow that passeth away. And the peace of God which passeth all vnderstanding, shall keepe your hearts & minds through Christ Iesus. This is the reioycing citie that dwelt carelessely, that said in her heart, I am, and there is none beside me: how is shee become a desolation, a place for beasts to lie downe in! euery one that passeth by her, shall hisse and wagge his hand. One generation passeth away, and another generation commeth: but the earth abideth for euer.

The sequence "shall pass" occurs 37 times in the KJV, while of course "shall passeth" doesn't occur at all:

No foot of man shal passe through it, nor foote of beast shall passe through it, neither shall it bee inhabited fourtie yeeres. For ye shall passe ouer Iordan, to goe in to possesse the land which the Lord your God giueth you, and ye shall possesse it, and dwell therein. Reioyce and be glad, O daughter of Edom, that dwellest in the lande of Uz, the cup also shall passe through vnto thee: thou shalt be drunken, and shalt make thy selfe naked. Heauen and earth shall passe away, but my wordes shall not passe away.

I'm not sure what sort of reference or joke Josh has in mind, but he's used the phrase before, so there's some resonance here. Maybe there's a pop culture reference that I'm missing (which would make this "the popcorn that passeth all understanding"), or maybe it just has a faux-pompous sound that fits the occasion.

What about Michele Bachmann's "Thou protestest too much"?

Well, to give credit where credit is due, Rep. Bachmann got the morphosyntax right. The problem is that she got the quotation wrong. The first level of wrongness is one that she shares with nearly everyone else who indulges in this quotation from Hamlet — misunderstanding what Shakespeare meant by protest. Wikipedia explains:

The quotation "The lady doth protest too much, methinks." comes from Shakespeare's Hamlet, Act III, scene II, where it is spoken by Queen Gertrude, Hamlet's mother. The phrase has come to mean that one can "insist so passionately about something not being true that people suspect the opposite of what one is saying."[1] This usage of the phrase is based on a misunderstanding of the meaning of the word "protest" as it was used in Shakespeare's day, as the "protest" of the lady is not a protest in the modern sense of the word, but an affirmation or avowal.

The phrase's actual meaning is, "I think the lady is promising too much." In the play, Hamlet's father has died, and his father's ghost has told Hamlet that he has been murdered (by Claudius). Hamlet has arranged the play for his mother Gertude and his uncle/stepfather King Claudius to watch: "The play's the thing, wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king." Hamlet wants to see if Claudius squirms or sweats at the point in the play where the woman's husband is murdered by her lover (or future lover). If so, he'll have some decent evidence that Claudius killed his father. Hamlet arranged for the woman in the play to promise ("protest") to her husband that if he dies she will never remarry. At this point, Hamlet asks his mother how she likes the play so far, and Gertude famously replies, "The lady protests too much, methinks." In other words, she's promising too much. Gertude is protecting her own conscience about having married Hamlet's uncle after his father died. Hamlet replies, "O, but she'll keep her word." He's rubbing it in that his mother hasn't lived up to the standard of the woman in the play.

And then, in a more specifically individual misquotation, Rep. Bachmann turned the play's third person form into a second person form.

I'm inclined to forgive that, because Shakespeare himself was not above loosely adapting plots and even lines from his predecessors. And in this particular case, he exhibits two interesting kinds of morphosyntactic variation across editions of the work. One from of variation is the -(e)s / -eth business, and the second illustrates the optional advent of "do-support". The first quarto (1603) and the first folio (1623) both have "The Lady protests too much", while only the second quarto (1604) has the usually-quoted version "The Lady doth protest too much". And whatever its form, this line is Gertrude's answer to a question in which Hamlet varies in his own do-support — the 1603 version is "Madam, how do you like this play?", while the 1604 and 1623 versions are "Madam, how like you this play?"

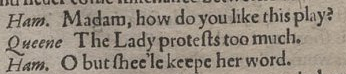

Ham. Madam, how do you like this play? Queene The Lady protests too much. Ham. O but shee'le keepe her word.

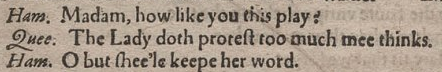

Ham. Madam, how like you this play? Quee. The Lady doth protest too much mee thinks. Ham. O but shee'le keepe her word.

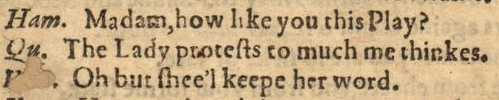

Ham. Madam, how like you this Play? Qu. The Lady protests to much me thinkes. Ham. Oh but shee'l keepe her word.

Has anyone done a systematic study of morphosyntactic variation across the various editions of Shakespeare's plays? If so, please tell us about it. If not, this would be a great term project.