Prosody and "elastic words" in Chinese

Language Log 2013-05-13

During my recent visit to Michigan, San Duanmu told me about some really neat work that he published last year as "Word-length preferences in Chinese: a corpus study", Journal of East Asian Linguistics 21.1: 89-114, 2012.

San starts from the observation that many Chinese words have two forms, a two-syllable form and a one-syllable frorm, whose meanings are more or less the same. For example:

煤炭 (méi tàn)煤 (méi)‘coal’學習 (xué xí)學 (xué)‘to learn; study’工人 (gōng rén)工 (gōng)‘worker’商店 (shāng diàn)店 (diàn)‘store’老虎 (lǎo hǔ)虎 (hǔ)‘tiger’印度 (Yìn dù)印 (Yìn)‘India’In "How many Chinese words have elastic length?", in Feng Shi and Gang Peng, Eds., Festschrift in honor of Prof. William S-Y. Wang's 80th birthday, 2011, San found that that

80%-90% of all Chinese words have elastic length. In addition, the percentage for verbs is higher than the average, and the percentage for nouns is higher still.

And he observes that

The long form may look like a compound, but it is not. For example, the long form of hu ‘tiger’ is laohu, which literally means ‘old tiger’. However, laohu simply means ‘tiger’, not ‘old tiger’, because even a baby tiger can be called laohu. Similarly, the long form of mei ‘coal’ is meitan, which literally means ‘coal-charcoal’ but actually means ‘coal’, not ‘coal and charcoal’.

But the one-syllable and two-syllable versions are not equally likely to be used in all contexts. Specifically, in a closely-associated two-word sequence, there are four logical possibilities:

2+2 2+1 1+2 1+1

Based on a quantitative analysis of the Lancaster Corpus of Mandarin Chinese, San's study found that

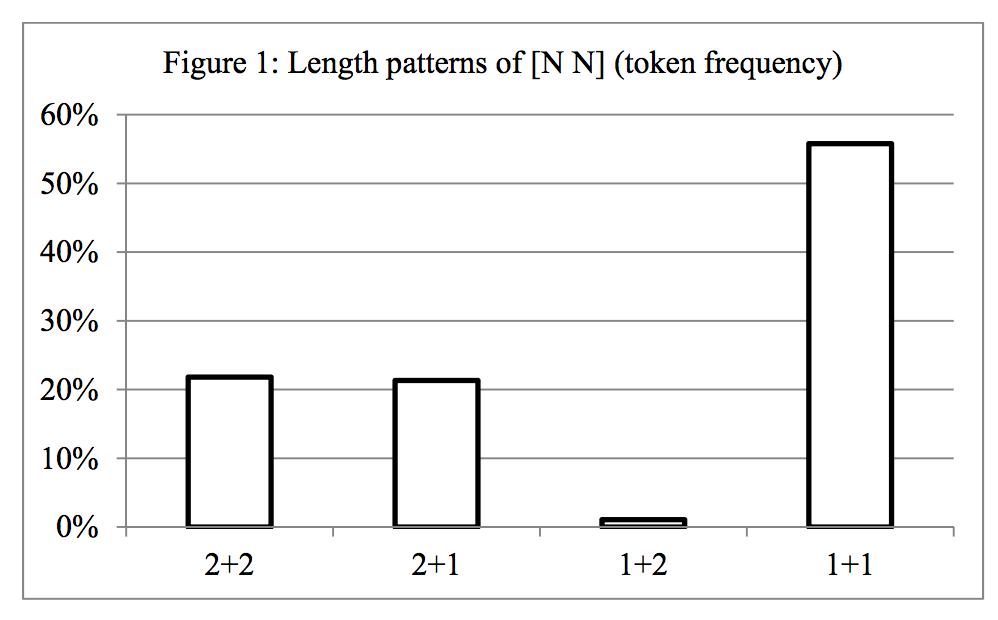

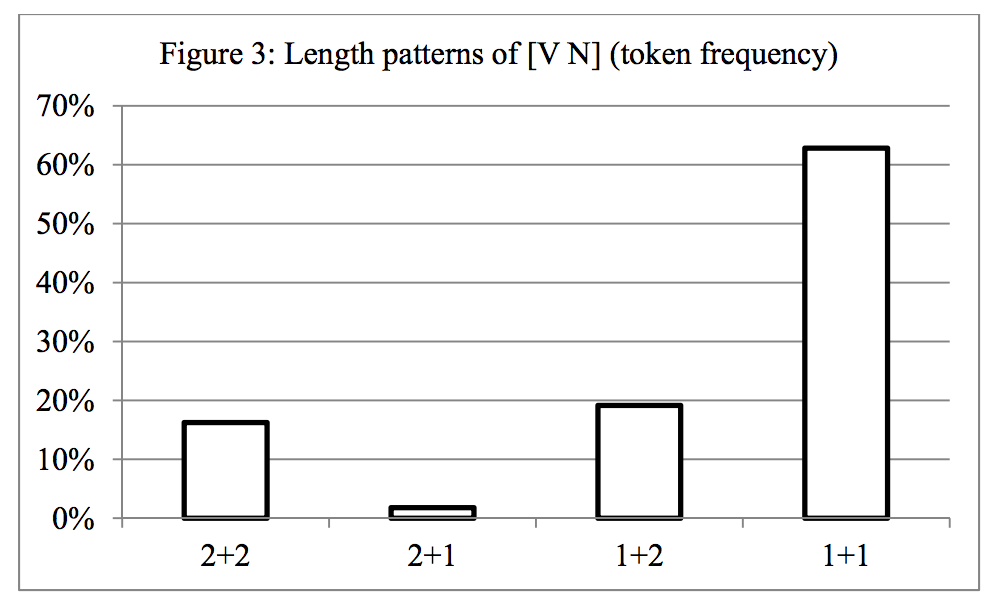

1+2 is overwhelmingly disfavored in [N N] and 2+1 is overwhelmingly disfavored in [V O]. In addition, it is found that apparent exceptions, ranging between 1% and 2%, are limited to certain specific structures, and when these are factored out, both 1+2 [N N] and 2+1 [V O] are well below 1% in either token count or type count.

Others have noted these regularities, though San's paper is the first to support the intuitions with systematic corpus-based counts.

A non-corpus-based illustration: in combining méi (tàn) "coal" with (shāng) diàn "store" to make a noun+noun combination meaning "coal store", we could have méi tàn + shāng diàn = 2+2, or méi tàn + diàn = 2+1, or méi + diàn = 1+1, but NOT méi + shāng diàn = 1+2.

And in combining zhòng (zhí) "to plant" with (dà) suàn "garlic", to make a verb+object combination meaning "to plant garlic", we could have zhòng zhí + dà suàn = 2+2, or zhòng + dà suàn = 1+2, or zhòng + suàn = 1+1, but NOT zhòng zhí + suàn = 2+1.

So to repeat, [N N] can be anything except 1+2, while [V O] can be anything but 2+1.

Why?

Some people have argued that this is a prosodic restriction: basically, in an [N N] structure, the first N should be stronger (and hence not smaller than) the second one; but in a [V O] structure, the object should be stronger than the verb. Others have argued for a syntactic or semantic treatment.

San observes that there are several reasons why a careful study of usage is helpful in answering these questions. For example, there are quite a few exceptions, such as 皮手套 pí shǒutào "leather glove" or 喜歡錢 xǐhuan qián "love money". Then there's the question of the relative frequency of the preferred patterns (2+2, 2+1, 1+1 for [N N], 2+2, 1+2, 1+1 for [V N]). And there are cases where different patterns exist for the same phrase, with slightly different meanings. And so on.

Here are a couple of graphs from the paper:

For San's explanation of the exceptions as well as the rules, you should read his paper, which is quite accessible for outsiders.

Corpus-based studies of this kind are becoming more frequent, for theoretical as well as practical reasons. I have a modest suggestion for making them more useful, which is to publish the details of the underlying annotations as well as the summary statistics and the resulting conclusions.

San does something like this in part, by adding an appendix that lists all of the 45 exceptional 1+2 [N N] examples and all of the 56 exceptional 2+1 [V O] examples from the Lancaster corpus. But he doesn't provide their detailed locations in the corpus, nor the identity and locations of the (much larger number of) regular cases.

The annotation of the regular cases is non-trivial, since the Lancaster corpus provides no annotation of syntactic bracketing. San had to find all the instances of noun-noun and verb-noun sequences not separated by punctuation, and then screen (a 10% sample of) these manually to determine the "error" rates for different subcases. His final numbers were determined by applying the resulting proportions to the total string-based counts.

Other researchers may well want to check or extend this annotation, or to look at other aspects of the differentiation among length patterns, in this or other collections of Chinese text. In doing so, they should be able to start from an exact documentation of San's annotations.

Obviously, it wouldn't make sense to offer such data as a traditional "printed" appendix (even if no one ever actually printed it out). But it would be easy to define a form of stand-off annotation that would encode exactly which cases were classified in which way; and the results could be published as "supplementary materials".

If such documentation became common, then it could be interpreted by interactive programs for browsing, annotating, or analysing corpora, just as people now use Praat TextGrids (or other common annotation formats) in the case of audio collections.