A Real Character, and a Philosophical Language

Language Log 2020-12-01

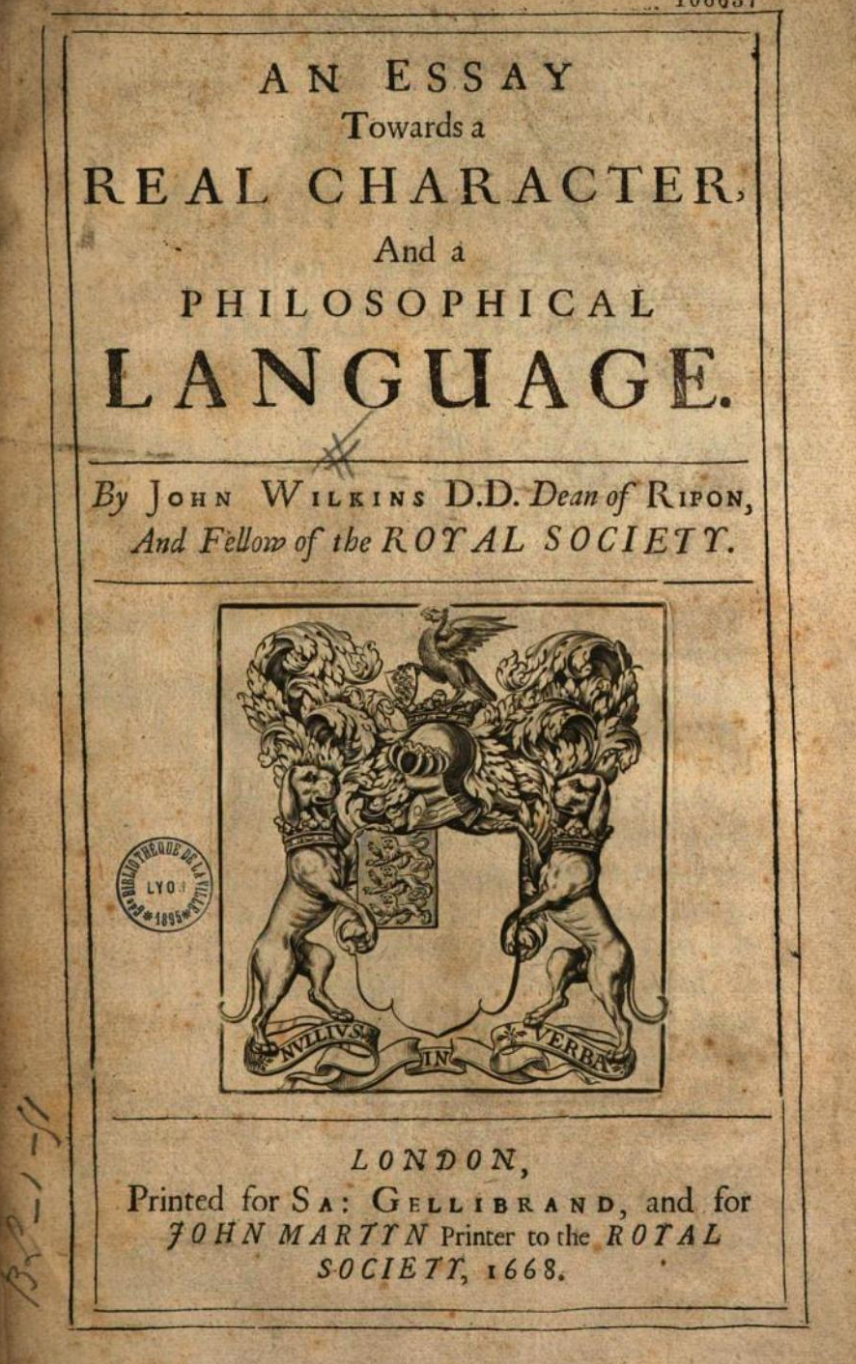

A couple of decades ago, in response to a long-forgotten taxonomic proposal, I copied into antique html Jorge Luis Borges' essay "El Idioma Analítico de John Wilkins", along with an English translation. This afternoon, a reading-group discussion about algorithms for topic classification brought up the question of a single universal tree-structured taxonomy of topics, and this reminded me again of what Borges had to say about Wilkins' 1668 treatise "An Essay Towards a Real Character, And a Philosophical Language". You should read the whole of Borges' essay, but the relevant passage for computational taxonomists is this:

[N]otoriamente no hay clasificación del universo que no sea arbitraria y conjetural. La razón es muy simple: no sabemos qué cosa es el universo. "El mundo – escribe David Hume – es tal vez el bosquejo rudimentario de algún dios infantil, que lo abandonó a medio hacer, avergonzado de su ejecución deficiente; es obra de un dios subalterno, de quien los dioses superiores se burlan; es la confusa producción de una divinidad decrépita y jubilada, que ya se ha muerto" (Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, V. 1779). Cabe ir más lejos; cabe sospechar que no hay universo en el sentido orgánico, unificador, que tiene esa ambiciosa palabra. Si lo hay, falta conjeturar su propósito; falta conjeturar las palabras, las definiciones, las etimologías, las sinonimias, del secreto diccionario de Dios.

[I]t is clear that there is no classification of the Universe that is not arbitrary and full of conjectures. The reason for this is very simple: we do not know what thing the universe is. "The world – David Hume writes – is perhaps the rudimentary sketch of a childish god, who left it half done, ashamed by his deficient work; it is created by a subordinate god, at whom the superior gods laugh; it is the confused production of a decrepit and retiring divinity, who has already died" ('Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion', V. 1779). We are allowed to go further; we can suspect that there is no universe in the organic, unifying sense, that this ambitious term has. If there is a universe, its aim is not conjectured yet; we have not yet conjectured the words, the definitions, the etymologies, the synonyms, from the secret dictionary of God.

Borges wrote that "No hay ejemplares de ese libro en nuestra Biblioteca Nacional" ("There are no copies of this book in our National Library"), but thanks to Early English Books Online, we can now read a searchable online version with human-corrected OCR, or peruse Google Books' digital facsimile of the 1668 printing.

Borges wrote that "No hay ejemplares de ese libro en nuestra Biblioteca Nacional" ("There are no copies of this book in our National Library"), but thanks to Early English Books Online, we can now read a searchable online version with human-corrected OCR, or peruse Google Books' digital facsimile of the 1668 printing.

Skimming the EEBO version turns up some interesting passages, e.g. this from the dedication:

[T]his design will likewise contribute much to the clearing of some of our Modern differences in Religion, by unmask∣ing many wild errors, that shelter themselves under the disguise of affected phrases; which being Philosophically unfolded, and rendered according to the genuine and na∣tural importance of Words, will appear to be inconsisten∣cies and contradictions. And several of those pretended, mysterious, profound notions, expressed in great swelling words, whereby some men set up for reputation, being this way examined, will appear to be, either nonsence, or very flat and jejune.

And tho it should be of no other use but this, yet were it in these days well worth a mans pains and study, con∣sidering the Common mischief that is done, and the many impostures and cheats that are put upon men, under the disguise of affected insignificant Phrases.

Or again, this from the Introduction:

In the first Part I shall premise some things as Pracognita, concerning such Tongues and Letters as are already in being, particularly concerning those various defects and imperfe∣ctions in them, which ought to be supplyed and provided against, in any such Language or Character, as is to be invented according to the rules of Art.

The second Part shall contein that which is the great foundation of the thing here designed, namely a regular enumeration and description of all those things and notions, to which marks or names ought to be assigned according to their respective natures, which may be styled the Scientifical Part, comprehending Vniversal Philosophy. It being the pro∣per end and design of the several branches of Philosophy to reduce all things and notions unto such a frame, as may express their natural order, dependence, and relations.

The third Part shall treat concerning such helps and Instruments, as are requisite for the framing of these more simple notions into continued Speech or Discourse, which may therefore be stiled the Organical or In∣strumental Part, and doth comprehend the Art of Natural or Philoso∣phical Grammar.

Later, Wilkins explains how words in his Philosophical Language ought to be arranged:

That structure may be called Regular, which is according to the natural sense and order of the words.

The General Rule for this order amongst Integrals is, That which governs should precede; The Nominative Case before the Verb, and the Accusative after; The Substantive before the Adjective: Only Adjective Pronouns being Particles and affixed, may without incon∣venience be put indifferently either before or after. Derived Adverbs should follow that which is called the Verb, as denoting the quality or manner of the Act.

There's a sort of proto-IPA, and also an anticipatory plagiarism (in 17th-C pronuncation) of John Wells' Lexical Sets.

In the chapter on Syntax, Wilkins notes that conventional orthography provides no way to mark Irony. I wish he had proposed one, but if he does, I can't find it:

The manner of pronouncing words doth sometimes give them a different sense and meaning, and Writing being the Picture or Image of Speech, ought to be adapted unto all the material circumstances of it, and consequently must have some marks to denote these vari∣ous manners of Pronunciation; which may be sufficiently done by these seven kinds of marks or Interpunctions.

- 1. Parenthesis.

- 2. Parathesis, or Exposition.

- 3. Erotesis, or Interrogation.

- 4. Ecphonesis, Exclamation or wonder.

- 5. Emphasis.

- 6. Irony.

- 7. Hyphen.

[…]

6. Irony is for the distinction of the meaning and intention of any words, when they are to be understood by way of Sarcasm or scoff, or in a contrary sense to that which they naturally signifie: And though there be not (for ought I know) any note designed for this in any of the Instituted Languages, yet that is from their deficiency and imperfection: For if the chief force of Ironies do consist in Pro∣nunciation, it will plainly follow, that there ought to be some mark for direction, when things are to be so pronounced.

For a sample of his labors' result, you can read Wilkins' annotated translation of the Lord's Prayer.