"Fading Language"?

Language Log 2022-12-23

People get confused about languages, dialects, registers, and scripts — and when journalists try to help, they often make things worse. For a good recent example, see Mujib Mashal, "Where Romantic Poetry in a Fading Language Draws Stadium Crowds", NYT 12/18/2022:

That more than 300,000 people came to celebrate Urdu poetry during the three-day festival this month in New Delhi was testament to the peculiar reality of the language in India.

For centuries, Urdu was a prominent language of culture and poetry in India, at times promoted by Mughal rulers. Its literature and journalism — often advanced by writers who rebelled against religious dogma — played important roles in the country’s independence struggle against British colonial rule and in the spread of socialist fervor across the subcontinent later in the 20th century.

In more recent decades, the language has faced dual threats from communal politics and the quest for economic prosperity. Urdu is now stigmatized as foreign, the language of India’s archrival, Pakistan. Families increasingly prefer to enroll children in schools that teach English and other Indian languages better suited for the job market.

In "Scripts, Scriptures and Scribes" (1/3/2008) I quoted from Bob King's 2001 paper "The poisonous potency of script: Hindi and Urdu":

Hindi and Urdu are variants of the same language characterized by extreme digraphia: Hindi is written in the Devanagari script from left to right, Urdu in a script derived from a Persian modification of Arabic script written from right to left. High variants of Hindi look to Sanskrit for inspiration and linguistic enrichment, high variants of Urdu to Persian and Arabic. Hindi and Urdu diverge from each other cumulatively, mostly in vocabulary, as one moves from the bazaar to the higher realms, and in their highest — and therefore most artificial — forms the two languages are mutually incomprehensible. The battle between Hindi and Urdu, the graphemic conflict in particular, was a major flash point of Hindu/Muslim animosity before the partition of British India into India and Pakistan in 1947.

[…]

There is a prodigal visual difference between the Devanagari script (also called Nagari) used to write Hindi and the Perso-Arabic script ordinarily used to write Urdu. The Devanagari script of Hindi is"squarish," "chunky," "has edges" — conventional characterizations all — written left to right, with words set off from each other by an overhead horizontal line connected to the graphemes and running from the beginning of the word to its end. The Perso-Arabic script of Urdu is "graceful," "flowing," "has curves," written right to left, with word boundaries marked as much by final forms of consonants as by spaces. The immediate visually iconic associations are: Hindi script = India, South Asia, Hinduism; Urdu script = Middle East, Islam. The graphemic difference between Hindi and Urdu is far more dramatic, for example, than the difference between the Cyrillic script of Serbian and the Roman script of Croatian.

[…]

One can easily imagine a condition of pacific digraphia: people who speak more or less the same language choose for perfectly benevolent reasons to write their language differently; but these people otherwise like each other, get on with one another, live together as amiable neighbors. It is a homey picture, and one wishes it were the norm. It is not. Digraphia is regularly an outer and visible sign of ethnic or religious hatred. Script tolerance, alas, is no more common than tolerance itself. In this too Hindi-Urdu is lamentably all too typical. People have died in India for the Devanagari script of Hindi or the Perso-Arabic script of Urdu. It is rare, except for scholars, for Hindi speakers to learn to read Urdu script or for Urdu speakers to learn to read Devanagari.

But the various common spoken forms of "Hindi" and "Urdu" overlap to such a great extent that the dialogue and song lyrics in Bollywood movies live mostly in the shared space. This has led to some controversy — see e.g. "Language in Bollywood: Hindi or Urdu?".

See also Shoaib Daniyal, "The death of Urdu in India is greatly exaggerated – the language is actually thriving" (scroll.in 6/1/2016), and "From love songs to kurta ads, Urdu is popular with Indians. Why do Hindutva backers hate it so much?" (10/24/2021).

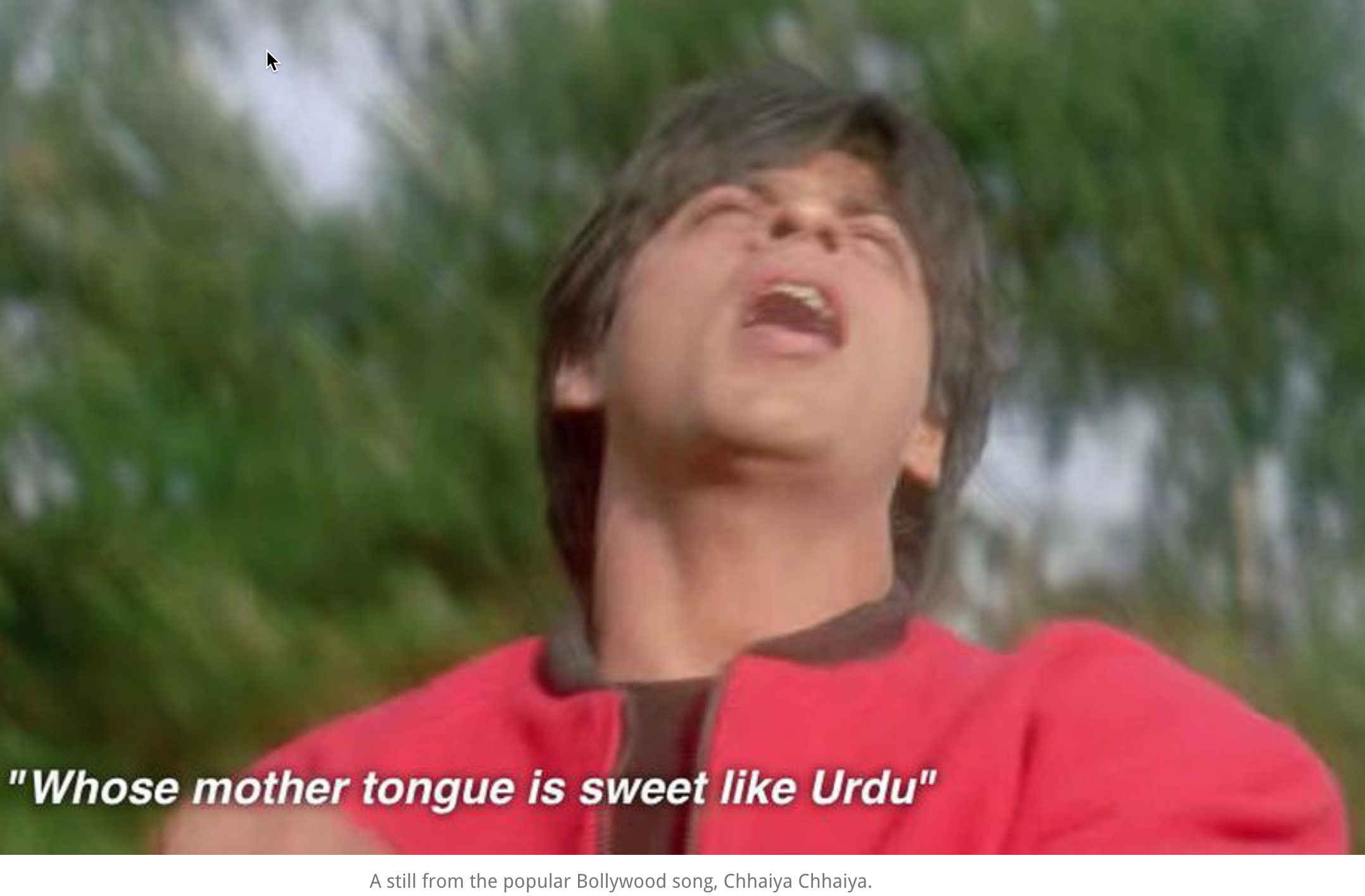

That last reference features this illustration of a line from the movie performance of a popular Bollywood song, "Chaiyya Chaiyya":

The full song, from the 1998 movie Dil Se, can be found in several versions on YouTube, including this one (posted 9 months ago and viewed 23 million times):

The lyrics page on genius.com for this song is presented in Latin script, where the cited couplet (at about 1:27 in the video above, or here with English subtitles) is rendered as

[Pre/Post Chorus: Sukhwinder Singh & Sapna Awasthi] Wo yaar hai jo khushboo ki tarah Wo jiski zubaan urdu ki tarah

Genius also offers a "Hindi version", in which the relevant lines are rendered as

[Pre/Post Chorus: Sukhwinder Singh & Sapna Awasthi] वो यार है जो ख़ुशबू की तरह जिसकी जुबां उर्दू की तरह

for which Google Translate produces the (semi-mangled) English version

He is the friend who is like the fragrance whose tongue like urdu

(Readers familiar with Bollywood Urdu/Hindi are invited to offer better translations and explications…)

There does not seem to be a version in Urdu script (whether Nastiliq or Naskh) — which I guess illustrates the meta-sociolinguistic problem we started with.

And for a bit more on Urdu script(s), see "Is the Urdu script on the verge of dying?", 6/29/2014, which references Ali Eteraz's 10/7/2013 "The Death of the Urdu Script", focused on digital Urdu text around the world.