Linguistic Laws

Language Log 2023-02-05

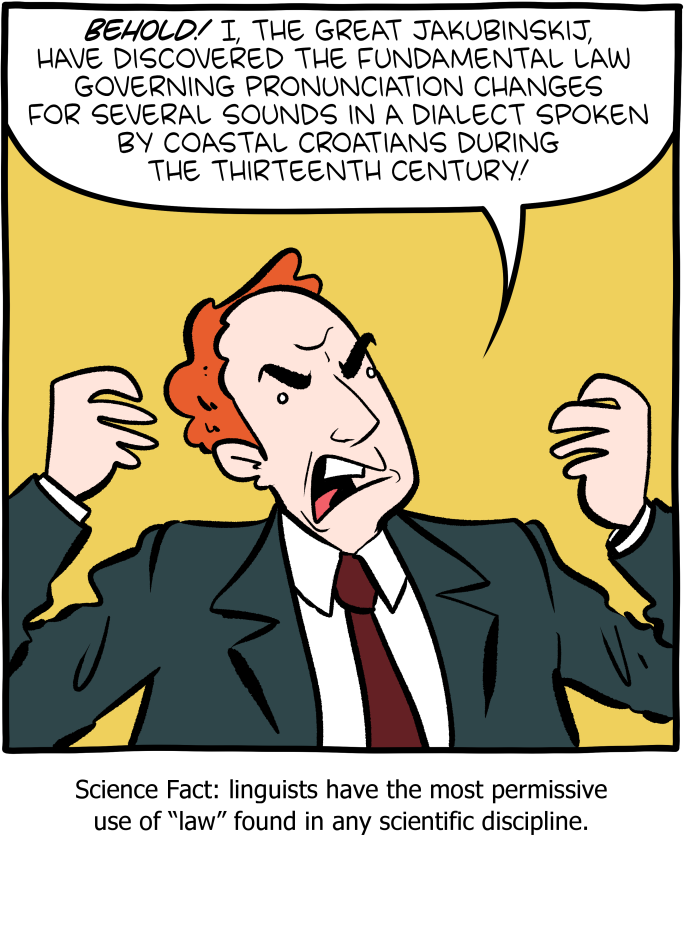

Today's SMBC:

Mouseover title: "This is the greatest Jakubinskij joke in the history of this medium. I believe the Eisners are taking nominations right now."

Mouseover title: "This is the greatest Jakubinskij joke in the history of this medium. I believe the Eisners are taking nominations right now."

The aftercomic:

Jakubinskij's Law does actually exist — as Wikipedia explains, "Jakubinskij's law governs the distribution of the mixed Ikavian–Ekavian reflexes of Common Slavic yat phoneme, occurring in the Middle Chakavian area."

Wikipedia does not yet have a page for the law's author, so to get minimal facts about Lav Jakubinski(j) we need to turn to the Hrvatska enciklopedija.

There have been a fair number of scholarly references to Jakubinskij's Law over the years, for example Elena Budovskaja and Peter Houtzagers. "Phonological characteristics of the Čakavian dialect of Kali on the island of Ugljan", Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics 1994:

As can be expected in this part of the Čakavian area, the dialect of Kali is 'i/e-kavian", i.e. it reflects Proto-Slavic jat as either a high or a mid front vowel. More often than not, the reflexes of jat are distributed according to "Jakubinskij's law": mid front before a "hard dental" (d, t, z, s, n, r, l not followed by j or a front vowel) and high front everywhere else.

I believe that we owe to the neogrammarians the idea that regular historical patterns of phonological change should be called "laws": Grimm's Law, Verner's Law, Grassmann's Law, and so on… From Wikipedia's article on Sound Change:

The Neogrammarian linguists of the 19th century introduced the term sound law to refer to rules of regular change, perhaps in imitation of the laws of physics, and the term "law" is still used in referring to specific sound rules that are named after their authors like Grimm's Law, Grassmann's Law etc. Real-world sound changes often admit exceptions, but the expectation of their regularity or absence of exceptions is of great heuristic value by allowing historical linguists to define the notion of regular correspondence by the comparative method.

Contrary to the cartoon's implication, names of the form X's Law have generally not been claimed by the discoverer X, but rather by subsequent investigators who need a term for the pattern in question.

And in recent (and/or less Germanic?) times, linguists have mostly used words like rule, rather than law, to describe regular patterns of sound change in synchronic progress, and have named particular examples with impersonal descriptive phrases, like the Great Vowel Shift (not "Jespersen's Law") or Canadian Raising (not "Joos's Law") or the Northern Cities Shift (not "Labov's Law").

Whatever other socio-cultural issues this terminological difference reflects, it implicitly recognizes the fact that the discovery of these named patterns is almost never the accomplishment of one single person.