The JAMA effect plus news media echo chamber: More misleading publicity on that problematic claim that lesbians and bisexual women die sooner than straight women

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2024-08-19

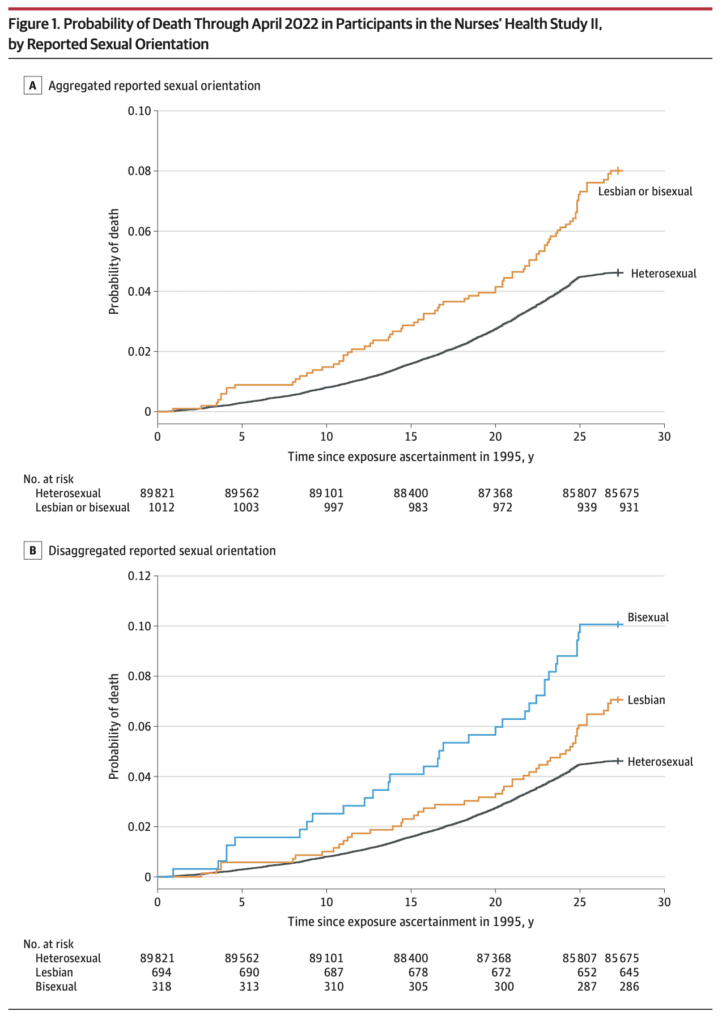

Last month we discussed a JAMA paper that included the above misleading graph and made strong claims that were not supported by data.

Since then, these strong claims have received further publicity. Here’s a news article uncritically reporting those claims, including this quote from one of the authors of the study:

One of the advantages of this study is that we were able to separate out bisexual and lesbian participants, because we had enough people and we followed them for long enough that we can actually look at those risks separately, which no other U.S. study has been able to do.

This is kind of a subtle issue, and it would be hard to expect a news reporter to do pushback on such a claim, but, no, a comparison of the 49 deaths among lesbians and 32 deaths among bisexuals in that study is noisy enough that differences between the two groups can be explainable by chance alone. Even their own reported comparisons did not reach a conventional level of statistical significance, and that doesn’t even get into the other statistical issues discussed above. See the above-linked post for details on that point.

Those survival graphs are so misleading—they make the evidence look much stronger than it is. It would’ve been the job of the statistician on the project to push back against these sort of noise-mining claims. I’m not saying the differences between the groups are zero, just that the data are sparse enough that, even aside from all other issues, they are consistent with underlying differences that could go either way.

It’s frustrating that the news media coverage of this is so unskeptical. See here, here, and here for more examples. JAMA’s prestige has to be part of the problem, and I think another problem is that seductively appealing graph (for people who don’t look at it too carefully). From one of those reports:

“These findings may underestimate the true disparity in the general U.S. population,” the authors wrote, adding that the study population “is a sample of racially homogeneous female nurses with high health literacy and socioeconomic status, predisposing them to longer and healthier lives than the general public.”

“We think that that means that our estimate is, unfortunately, conservative,” McKetta noted.

This sort of thing is frustrating, and we see it so often: researchers see some pattern in noisy data and then they expect that the true effect is even larger. All things are possible, but experience and Bayesian logic goes the other way.

I’d like to think that continuing coverage of the replication crisis in science would make this issue clearer to people, but I fear that most researchers see the replication crisis as something that happens to other people, not to them.

This is another reason I prefer the neutral term “forking paths” to the accusatory-sounding “p-hacking,” which sounds like a bad thing that people do. Honesty and transparency are not enough; making statistical errors doesn’t mean you’re a bad person, and sincere and qualified researchers can make statistical mistakes.

There’s also this echo chamber thing, where if you are asked to talk about a topic multiple times, and you never get any pushback, it’s natural to make stronger and stronger claims, going far beyond the data that were used to justify those claims in the first place. We’ve seen this with the sleep guy, the Stanford medical school professor, the glamorous business school professor, and many others. When there’s no pushback, it’s all too easy to slip from experimental data to strong claims to pure speculation.

Again, I’m not trying to disparage the study of health disparities. Indeed, it is because the topic is important that I’m bothered when researchers make avoidable mistakes when studying it.