If you want to play women’s tennis at the top level, there’s a huge benefit to being ____. Not just ____, but exceptionally ___, outlier-outlier ___. (And what we can learn about social science from this stylized fact.)

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2024-09-06

If you want to play basketball at the top level, there’s a huge benefit to being tall. Not just tall, but exceptionally tall, outlier-outlier tall. If you’re an American and at least 7 feet tall and the right age, it’s said that there’s a 1-in-7 chance you’ll play in the NBA (but maybe that’s an overestimate; we’re still looking into that one).

Here’s another one for you. If you want to play women’s tennis at the top level, there’s a huge benefit to being ____. Not just ____, but exceptionally ___, outlier-outlier ___.

Take a guess and continue: The answer to this fill-in-the-bank is “rich.”

Paul Campos reports:

At the moment, five American women are ranked among the top 30 women tennis players in the world, per the current WTA rankings. . . . two of the five women have a billionaire parent.

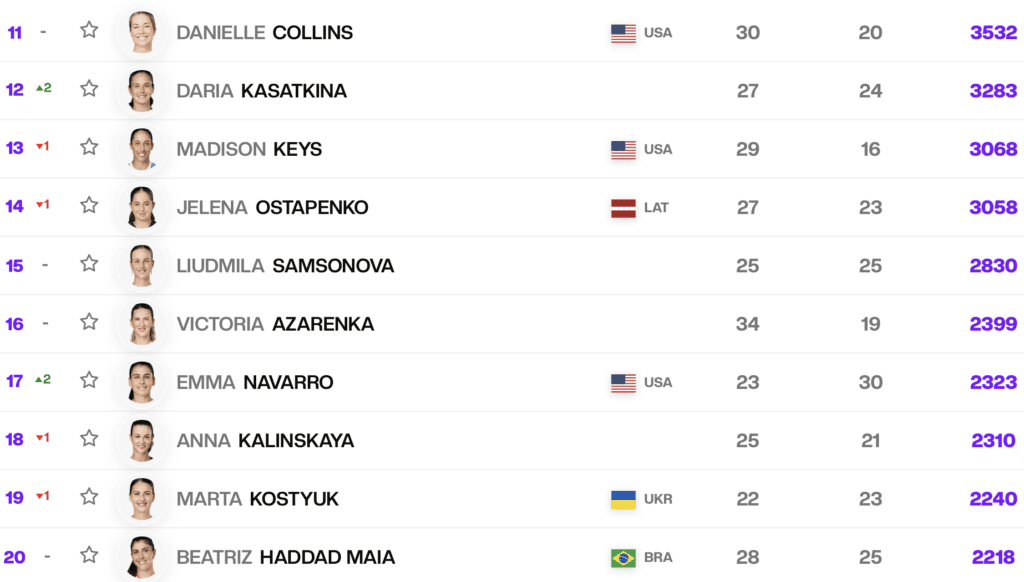

Whaaaa? OK, I googled *wta women’s tennis ratings*, which takes us to this page:

Actually, those 5 Americans are in the top 20, so I don’t know why Campos said “top 30.” Maybe in tennis the top 30 is a thing that people talk about, I dunno.

In any case, yeah, Campos ain’t kidding. Google the five U.S. players above, and indeed two of them are literal children of billionaires. According to wikipedia, one of those billionaires worked for Goldman Sachs and Citigroup before founding his own investment services company; the other worked for Getty Oil before founding his own natural gas drilling company, which he eventually sold to some major oil companies.

The other women in the top 20 are mostly children of top-tier athletes: some pro tennis players, an internationally competitive ping-pong player, badminton, football, basketball, etc. A mix of sports, actually. And then there are the two children of billionaires.

Campos runs the numbers:

The top 30 women tennis players in the world currently range in age from 17 to 34. Using that — unrealistically but we can’t make this too complicated too early in the morning — as a hard cutoff for the possible age range of top 30 in the world women tennis players, that means you have 18 relevant birth years: 1990-2007 (more or less). How many girls were born in America, collectively, in those 18 years? The answer is about 37 million. So if you were a girl born in America between 1990 and 2007 your odds of being one of the top 30 women tennis players in the world in July 2024 are about 7.4 million to one.

He continues:

But let’s toss just one little confounder into this equation: What if your parent happens to be a billionaire? There are currently 756 billionaires in the USA.

If billionaires average one daughter each, and, say, half these daughters are currently between 17 and 34 years old, then that would be 378 tennis-pro-age daughters out there, so the probability that a randomly-selected one of them is a world top 30 tennis player is 2/378, or about 1 in 200. OK, that’s just a rough calculation, but you get the point.

There are several interesting angles here.

1. Meritocracy. Campos writes that “this apparently trivial stat illustrates quite beautifully just how absurd the idea of ‘the meritocracy’ really is.” I wrote about this a few years ago in a post entitled, “Meritocracy won’t happen: the problem’s with the ‘ocracy’.”

The logic goes as follows: Under meritocracy, the people with merit get the spoils; they run the place—that’s the “ocracy” part! One of the goodies you get from merit is the ability to get nice things for your kids, things like fancy cars, houses in good neighborhoods, and . . . successful careers. Like being a top-20 tennis player.

The point is that seeing ultra-rich kids becoming tennis champions is not a sign that our society is not meritocratic (sorry, reader, for the double negative there!). Actually, it’s a strong indicator of meritocracy: these dudes had the merit to succeed in business, and they used their resulting “ocracy” to give their kids what it took to reach the top. If it hadn’t been that, maybe the kids would’ve become world-class musicians, or comedy writers, or artists, or some other field where some combination of connections and training can give you that leg up.

2. Paradigms about fairness in the economy. The 7-footers-in-the-NBA statistic tells a story about economic efficiency. Pro basketball pays so well and gets so much publicity that it sucks some large percentage of all the available talent in the country, at least to the extent that “basketball talent” is associated with extreme height and some minimal level of athleticism. In contrast, the billionaires’-daughters-in-professional-tennis tells a story about economic inefficiency. There’s so much slack in professional women’s tennis that extreme wealth plus high motivation are enough, in themselves, to give someone a solid shot at the top echelon.

You can see why the NBA story would gain traction on the right; see here and followup here, where Tyler Cowen writes, “the NBA shows that it is possible, over time, to do a much better job of both finding and mobilizing talent.” And you can also see how the women’s tennis story fits a narrative on the left; indeed, in his post Campos makes an explicit connection: “taking money from the rich and giving it to everybody else is both the right thing to do — see statistics on women tennis players above, which illustrate just how preposterous the idea is that people “earn” their social privilege — and good politics.” Pick your sport, pick your story.

3. NBA vs. women’s tennis. Bill James wrote about the professionalization of baseball during the past 100+ years, characterized by a greater degree of seriousness at all levels: players starting younger, being paid more, becoming more specialized in their skills, working out during the off-season, being drawn from a wider group of the population, throwing hard and swinging hard on every pitch, and a few other things I can’t quite remember. The modern NBA is pretty much all these things. As for women’s tennis: the players start young and the pay at the top is not bad, but clearly they have far to go on the “being drawn from a wider group of the population” thing.

Taking a group of 400 or so daughters of the super-rich, there’s no reason to expect any stupendous athletic talent, pretty much mo more than you’d expect from 20 years of high school graduates from some random town that graduates 20 women a year. That said, there’s a lot of athletic talent out there in the world, just as there’s a lot of musical talent. If you think of 400 people from your high school, you can probably recall some very talented athletes. Not world’s best, but still awesome, the sort of kids who would be much better than you in any sport they might try, just naturally athletic and motivated to win. For fully-professionalized sports, “awesome in your high school class” won’t do it—minor-league baseball is full of local heroes who couldn’t make it up to the highest levels—but in a “thin” sport such as women’s tennis, a 1-in-400 level of ability seems to be enough.

4. Billionaires vs. millionaires. A baffling aspect of the women’s tennis story is that these women don’t just come from rich families; they come from super-super-rich families.

What’s the mechanism by which a billionaire’s daughter becomes a top-20 tennis player? To start with, it helps for the billionaire to be a sports fan so that he’s motivated to give his daughter all the advantages: private coaching, chartered flights to tournaments, etc. The only thing that’s puzzling me here is that you don’t really need a billion dollars to do all this. A few million should suffice. Meanwhile there are so few billionaires out there. What happened to the ordinary multi-millionaires, those parents who could easily afford private coaching starting at age 0 and all the transportation their kids could possibly need?

I can only speculate here. My guess is that being a billionaire doesn’t just give you the resources to give your child every possible advantage; it also gives you a sense of entitlement. If you’re a normal parent in this country, and your kid shows some ability—and, remember, someone at the 99th percentile of athletic ability really will be impressive—then you’d encourage your kid to play, you might enroll your kid in a sports camp, and if you’re really into sports, you might spring for private coaching, at whatever level matches your income. If you’re wealthy, same thing except that you can afford a membership at the local country club and top coaching. But if you’re really really really wealthy, you think, “Hey, my kid could be a world champion.” Why not? If you’ve personally parlayed your business efforts into ownership of a bank or an oil company or whatever, it could just seem natural that your kid could apply herself and reach the athletic summit. So you’ll push your daughter that much more, or she’ll push herself, having internalized the I’m-a-billionaire-so-I-can-get-everything-I-want attitude.

I dunno. This still doesn’t explain it all to me. I’ve heard enough about rich people in the suburbs and their kids doing 30 hours a week of sports training, that I can only assume there are other rich people in the suburbs whose kids are doing 60 hours a week . . . I guess that if you’re a mere millionaire and you want your daughter to do all this and become a tennis star, it’s still unlikely—but maybe kinda worth it because she’ll still get into Stanford on the tennis team—but if you have an actual billion dollars it’s somehow that much more likely to happen? I remain somewhat baffled.

5. The utility of money. There’s this whole debate in economics about whether money buys happiness. Everyone seems to agree that going from poverty to the middle class is a plus, as is going from the middle class to the upper middle class. After that, there’s some dispute about the marginal value of additional bucks. Leftists like to say that, after a certain point, extra money doesn’t make people happy, so why not redistribute it. Rightists are skeptical about claims of a threshold and point to findings that, even at the high end, money doesn’t just buy you a jetski made of diamonds, it also helps with happiness and life satisfaction. At the same time, right-leaning economists also will often play the populist card and explain why stuffed shirts who buy art or drink expensive wine or go to the symphony or whatever are really being conned. I think the rule is that if the expense is considered high-class, economists will want to puncture the bubble, but if it’s of the man-of-the-people variety (I guess that would include things like fast cars and boats and expensive steaks, but not Van Goghs or vintage wine), they’re inclined to say the money has been well spent.

OK, I drifted there for a moment. What I wanted to say is, this tennis thing is a great example of the continuing utility of money. If you want your daughter to be a top-20 tennis player, there’s something about those extra zeroes at the end of your net worth that makes a difference. 2,000,000,000 really is better than 20,000,000—even though, from an instrumental perspective, it’s hard to see the difference. As noted above, I don’t fully grasp the mechanism, but this is where the data point.

Summary

It’s amazing how much social science we can squeeze out of this one stylized fact. As the saying goes, God is in every leaf of every tree.