Different modes of discourse

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2013-03-15

Political/business negotiation vs. scholarly communication.

In a negotiation you hold back, you only make concessions if you have to or in exchange for something else. In scholarly communication you look for your own mistakes, you volunteer information to others, and if someone points out a mistake, you learn from it. (Just a couple days ago, in fact, someone sent me an email showing a problem with bayesglm. I ran and altered his code, and it turned out we had a problem. Based on this information, Yu-Sung found and fixed the code. I was grateful to be informed of the problem.)

Not all scholarly exchange goes like this, but that’s the ideal. In contrast, openness and transparency are not ideals in politics and business; in many cases they’re not even desired. If Barack Obama and John Boehner are negotiating on the budget, would it be appropriate for one of them to just start off the negotiations by making a bunch of concessions for free? No, of course not. Negotiation doesn’t work that way.

I got to thinking about this topic after some blog exchanges with Ron Unz, a political activist (I’m using that term not in any negative way but merely as a description; for example, Unz’s Wikipedia entry describes him as a “former businessman and political activist”) who wrote an article a few months ago claiming, among other things, that Harvard discriminates in favor of Jews in its undergraduate admissions. See here and here for lots of details. The short version is that, at first I felt no particular reason to doubt his numbers, but after seeing more data, it became pretty clear to me that Unz had made some mistakes in classification and mistakes in data analysis. As I’ve emphasized throughout, this does not make all of Unz’s larger claims false; what this new information does is change the status of Unz’s article from a data-based analysis to an anecdote-based opinion piece containing numbers and comparisons of uneven quality.

OK, now back to today’s topic: different modes of discourse.

Consider Unz’s reaction to the data and comments provided by Janet Mertz, a professor of oncology at the University of Wisconsin who’s published two peer-reviewed articles on demographics of high achieving math students. Mertz came into the picture to shoot down two of the most visible numbers in Unz’s article—two numbers that made it into the New York Times, thus reaching a much broader audience than the readership of the American Conservative and Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science. Unz wrote, “During the 1970s, well over 40 percent of the [U.S. Mathematical Olympiad team] were Jewish . . . However, during the thirteen years since 2000, just two names out of 78 or 2.5 percent appear to be Jewish.” Mertz, however, reports from direct contact with the students that over 12% of Olympiad team members since 2000 were Jewish, and she estimates 25-30% in the 1970s. It seems that Unz’s claim of 44% in the 1970s came by incorrectly including as Jewish any student with a German or Polish name even though many of them were found by Mertz to be Christian; on the other hand, in the 2000s, he no longer counted such names as Jewish and, even, failed to count as Jewish a student with an clearly Israeli-Hebrew name.

Going from a factor of 17 to a factor of 2 or 2 1/2, that’s a huge deal. At a direct level, it changes the flavor of one of Unz’s main points (“the strange collapse of Jewish academic achievement”) while, indirectly, it casts doubt on any estimates he creates based on identifying people’s ethnicity by name.

Unz recently accepted his error on the low number (although he shades things a bit by rounding up his original guess from 2.5% to 3% and reporting Mertz’s number as 12% rather than “over 12%”) but he seems to be standing fast on his claim of 44% for the 1970s, which seems odd to me given that it is based on his subjective ability to recognize Jewish names, an ability which he clearly doesn’t seem to have, at least not for these data.

OK, so far we could just be seeing some garden-variety stubbornness. Unz worked hard in compiling his numbers and in writing his article, so he’s understandably reluctant to admit some of this effort was wasted.

But here’s the interesting part. In the same blog entry where he admits error on the 2.5%, Unz writes:

The angry criticism of Prof. Mertz and “NB” had been floating around the Internet for some time, and had been widely ignored or dismissed.

So he’s known “for some time” that an expert on the demographics of math competition participants thought his numbers were wrong, and his reaction was to “ignore” and “dismiss” her? From an academic standpoint, this seems strange. We take criticisms seriously. When an expert (or even an informed outsider) says our numbers are wrong, we listen (even if we don’t end up agreeing).

But it all looks different if you take this as a negotiation or debate. Remember the Obama-Boehner story? Hold on to everything, don’t make any concessions till they drag it out of you. That seems to be what’s going on here. For some period of time, Unz has known that an expert in the field thinks his numbers are off by a factor of 5. But he sits on it and then after much criticism on many points, he admits a couple of mistakes but avoids comment on others. Savvy negotiating strategy. That’s how they do it in Washington. And, again, that’s how they should do it. If Obama (or, for that matter, Boehner) just started making unforced concessions, we wouldn’t admire the guy. We’d think he’s weak. And we’d be right. In a negotiation, you don’t get credit for openness. You gotta play by the rules.

So, I think what’s happening is that Unz and the rest of us are playing different games. We’re playing the academic research game, he’s playing the politics game.

Again, I’d better interject that I think politics is just fine. I’m a political scientist! I completely respect Unz’s choice to be a political activist and spend his life trying to change the world through political means (or to stop others from instituting what he believes would be negative changes). Calling Unz a political activist or politically-motivated is not an insult. It’s who he is. Unz made the choice not only to interpret the world but to change it, and that’s a choice we can all respect. He has every right to spend his time and money in this way.

But it gets tricky when academic and political norms collide. Unz is behaving in a perfectly reasonable way politically, dodging criticism as much as he can, fighting it where appropriate, and occasionally making a strategic concession of as little as possible in order to stay ahead of the story. This is what Mayor Bloomberg does, it’s what Paul Ryan and Hillary Clinton do, etc.

From an academic perspective, though, this kind of strategic behavior just comes off as weird. Listening to criticism and recognizing our errors isn’t just good scientific ethics, it’s also good for us. Consider this story, for example. After the 2008 election, I’d posted some colorful maps based on polling analysis, estimating how people from different demographic groups voted in different states. Lots of people loved the maps, but then I got one criticism from the political blogger Kos. He was the only person out there criticizing me, and indeed his criticism was aggressive in tone. It would’ve been easy for me to ignore him, to laugh it off and to say that thousands of people had seen my graphs and he was the only one to complain. I could’ve even questioned his motives. But did I? No. I took the criticism seriously. And it turned out he was right! Fixing my errors took months of research, but it was worth it. Yes, you heard that correctly: a kick in the pants from Daily Kos was a key input to this American Journal of Political Science paper.

If I’m not too proud to listen to Kos, there’s no reason Ron Unz should be too proud to listen to Janet Mertz. And, indeed he did, but it took him awhile to do so, and his admission is still only partial (for some reason he seems to continue to take his 44% number as fact) and so grudging that he’s still a long ways from making forward progress. For example, rather than criticizing himself for ignoring and dismissing Mertz’s accurate points, he criticizes her for sending her criticisms by email. That’s totally wack. When people point out errors to me by email, I appreciate the free information!

As they say in AA (or someplace like that), it’s only after you admit you’re a sinner that you can be redeemed. I know that I’m a sinner. I make statistical mistakes all the time. It’s unavoidable. Unz still has not reached that stage. Or maybe he does realize he’s made some big mistakes but he’s holding back on conceding them until he feels the time is right. I have no idea; I suspect it’s a mix of the two.

I have no reason to think Unz is insincere in what he writes, any more than I think Obama, Boehner, etc. disbelieve the economic policies they espouse. They’re just playing a complicated game in which communication is itself part of the strategy. In Unz’s case, he either knew for weeks or months that some of his numbers were wrong but refused to admit it, or he saw Mertz’s criticism but did not look at it. Neither of these reactions looks good to an academic, but, politically, they might have been smart gambles.

In his most recent post, Unz has moved in the direction of criticizing me as well, writing:

Individuals who become emotionally involved with a particular position of ideological or ethnic advocacy may lose their ability to dispassionately analyze data, and this intellectual failing may sometimes even apply to award-winning Ivy League statistics professors.

I agree. Even Ivy League statistics professors can go astray! I strongly believe Don Rubin analyzed his data honestly when he was being paid by the cigarette companies, but not everyone agrees with me on this. And some people felt that McShane and Wyner were misled by ideology when writing their controversial article on global warming for the Annals of Applied Statistics. As to my own writings, I’m subject to all the human flaws we all hold within ourselves. In this particular case, though, I don’t find Unz’s speculation convincing. Here’s what I wrote earlier regarding my interests in the matter:

I personally have connections both to Harvard and to Jews, so you can make of this what you will. All I can say on that account is that, when Unz’s article came out a few months ago, I had no problem presenting its claims as stated; it was only after receiving some recent emails with detailed statistics that I got the impression that Unz’s numbers were mistaken. What Unz did seems reasonable from a distance (and I can understand why he made the choices he did in making his estimate), but his conclusions don’t seem to hold up on closer inspection.

I think Unz is in a difficult position and I don’t know an easy way out for him. When I posted a couple weeks ago, I hoped/expected he would learn from the criticism, revise his numbers, and come up with a more nuanced picture of college admissions and ethnicity. He’d see the data showing a factor of 2 or 2 1/2 (rather than a factor of 17) decline in the proportion of Jews in the Olympiad and see this as a moderate decline explainable by increased competition and demographic change; he’d see that a calibrated analysis shows the Jewish enrollment at Harvard to be comparable to the rate of academically high-achieving Jews in the relevant population; and so on. Some of what he said in his original article still goes through, but he would need more nuance.

But it didn’t happen that way, and I think I’m starting to understand why. Unz is in the arena, he’s been a public figure for decades, and lots of people are angry at him before he says a single word. He gets lots and lots of political attacks, and it’s natural for him to treat all criticisms—from academics and non-academics alike—as political. Now, think about it. If you’re being criticized, year after year, on purely political grounds, it’s probably appropriate for your first reaction to be to fight and defend, not to examine your own writings for errors. What happens when an AFL-CIO researcher reads a new salvo from the Chamber of Commerce? Does he say: “Hey, those business guys have a point! Maybe I’m wrong about that whole collective-bargaining thing after all”? No, of course not. Instead he’ll look to see if the report reveals any weaknesses in his argument, but not with any expectation or intention of changing his thinking but rather so he can strengthen his claims. It’s a propaganda war. One might consider this a version of Kuhnian “normal science” but I don’t think so. Even a non-revolutionary scientist can only make serious progress by questioning his or her own assumptions.

Another possible reason for Unz not to admit some flaws and take a strategic retreat is, of course, that he honestly doesn’t think he made any mistakes (beyond the very few he admitted in his follow-up post). This is possible, but it just pushes the question back one step, as to why he would trust his demonstrably wrong counting procedure over the estimates of an expert. And it also doesn’t resolve why he sat on the criticisms for awhile without acknowledging his errors.

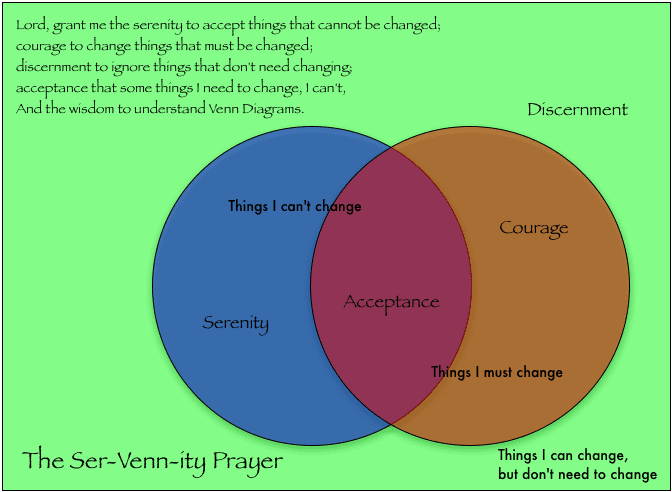

My guess is that Unz sits in some sort of intermediate state (as with the cat in the famous scenario pictured above). At some level he realizes his numbers are iffy. But at the same time he believes so strongly in his conclusions that I suspect he feels that even his false numbers are true in some deeper sense. Thus, for example, Unz tried to explain away the 12%+ Jews in recent math olympiads by claiming that many were recent immigrants. That claim also turned out to be wrong, but the very fact that he made the attempt indicates to me that he was trying to preserve all he could of his earlier views. From a statistical standpoint, this makes no sense: after all, if it’s informative to learn that the proportion of Jews in the math olympiad declined by a shocking factor of 17, then it should be informative (in the other direction) that the decline is only a factor of 2 or so. Surely our first response to the disproof of a shocking-but-surprising claim should be to be un-shocked and un-surprised, not to try to explain away the refutation. From a political standpoint, though, criticisms are not to be taken at face value. And once Unz feels that he’s in a battle, the rules all change, as discussed above. When you feel you’re attacked, anything goes.

A couple more things (for now)

1. A reader of this blog might reasonably ask: Why devote so much time to the case of a minor political figure who self-published some mistaken statistical claims? The short answer is that some of these numbers appeared in the New York Times. But that’s not the full answer, given that newspaper columnists make mistakes all the time (as do I). What really got me going in this case was a feeling of responsibility, in that I too had initially reported and reacted to Unz’s claims without skepticism. This then got me interested in the larger issue of how such numbers get put into wide circulation, and the corresponding difficulty in retracting them. First I expressed frustration that David Brooks issued no retraction, then I got to thinking about Ron Unz’s motivation in not admitting his mistakes. The larger question of scholarly discourse vs. political negotiation seemed important to me.

2. I’m not placing scholarly values above political values, nor am I implying that scholars always act in how I define the “scholarly” way. Of course not! Indeed, we speak of “academic politics” and so forth to discuss scholars behaving politically. Politics is important, and if you’re running a campaign of some sort, it’s not in general best for you to lay all your cards on the table. It can make perfect sense to fight every concession, kicking and screaming. I’m not much of a politician myself, and I respect those political skills that I do not have. All that said, I do find it frustrating when people behave in “political” ways. It doesn’t make me comfortable, hence this post.

3. In his recent post, Unz analogized his critics to “litigators who choose to completely ignore the overwhelming volume of the facts in a case but spend all their time angrily pounding the desk on an insignificant one hardly demonstrate the strength of their position.” I do not think this analogy is appropriate. First, while I have not been “angrily pounding the desk,” I can understand how Janet Mertz and my other correspondent might be drawn to anger, given that their comments were valid and clearly stated, yet had been (in Unz’s words) “ignored or dismissed.” That would make me angry too! Second, although (as I’ve written many times) several of Unz’s points remain relevant even after his errors are corrected, his claim of Harvard discriminating in favor of Jews and his claim of a dramatic drop in Jewish accomplishment do not hold up to scrutiny. These claims may well be a minor part of Unz’s bigger picture but they did make their way to the New York Times.

4. I thought twice about posting all of this because I fear it will annoy Unz, and (despite what you might think based on reading this blog), I have no desire to make more enemies in life. But on balance I think the point about modes of discourse is important, and I think it is in the context of a live story that this all comes out, so I wanted to make the post. To Unz and his friends, let me just say what I told David Brooks, that as a statistician I feel very strongly about the use of numbers. I have no desire to silence Unz. Rather, I feel (from a scholarly perspective) that whatever arguments he seeks to make will be stronger when attached to good data and clean statistical reasoning.