“What do you think is the ideal number of children for a family to have?” Two different statistical measurement challenges arise from this one question on the General Social Survey.

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2025-11-21

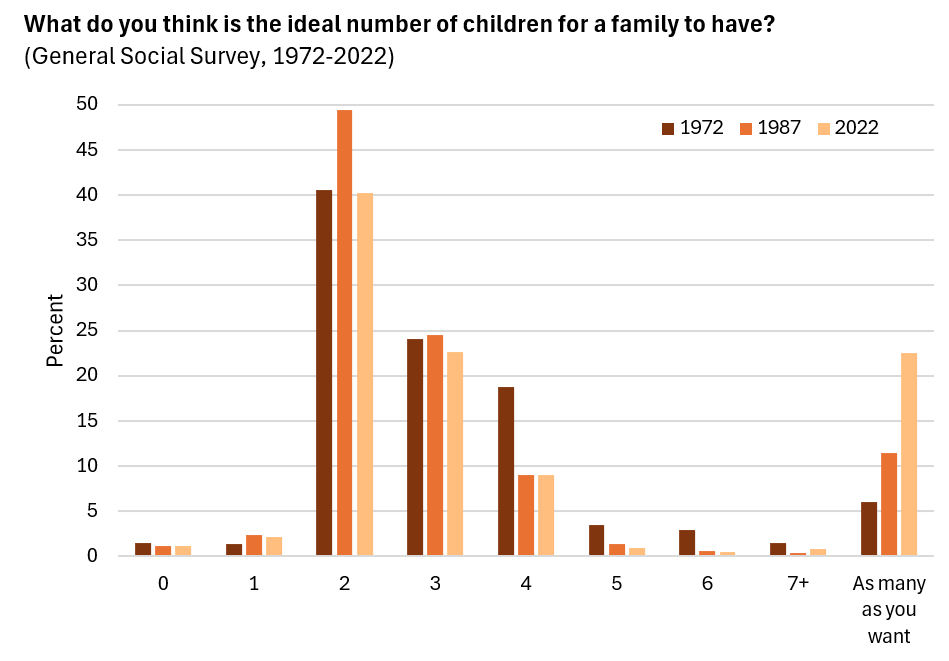

Philip Cohen shares the above graph.

There’s a lot to chew on here. First, what is the question asking, exactly? As Cohen says, “This is a question of normative views, not how many children people want themselves (which we would call intention or preference).” The “normative views” thing is interesting, in part because the ideal number would depend on the family. Indeed, even framing the question as “for a family” could be taken to imply that the number of children would be positive. I’m actually surprised that so few respondents gave “1” as an answer. It makes sense that 2 is the most common response, and it’s interesting to see the time series; I’m just not quite sure how to think about these responses. Indeed, I’m not sure how I myself would respond to the question!

Cohen focuses on a different aspect of the above graph, which is the increasing number of people who respond, “As many as you want.” Whassup with that? Cohen writes:

The category has gotten big enough that you can no longer ignore it, as many analysts have. The worst culprit may be Lyman Stone, who has repeatedly used the contrast between ideal and reality to promote pronatal policy, as here and here, where he used it to declare, “most women achieve less than their desired fertility.” The question does not measure respondents’ desired fertility, but rather their normative ideal.

I agree with Cohen that it does not make sense to use the “ideal number” question to represent “desired fertility.” Lyman Stone writes, “What if we give female survey respondents a bit more latitude, and ask them how many kids they’d ideally like to have?” But the “ideal number of children” question is not asking people how many children they would like to have. Again, this can easily be seen by looking at how few 0’s and 1’s there are on the above graph. There are people out there who don’t want any kids themselves, but they could still think that 2 is “the ideal number of children for a family to have?”

But back to the “As many as you want” option. Here’s Cohen’s explanation:

The major difference is the survey is increasingly done online. From 2004 to 2018, the vast majority — roughly 80-90% — of interviews were done in person. In 2021, because of the pandemic, none were in person, 12% were by phone and 88% were online. In 2022, 46% were online (this is the MODE variable). How does this affect ideal family size? In the 2022 codebook, GSS calls this variable a “classic example of differences in stimulus between interviewer-administered and self-administered modes.” In person, they don’t give people the choice of “as many as you want,” they just record it if people spontaneously offer that opinion. But in the web version, that option is now on the list presented to them. As a result, the number of people choosing this answer has shot up.

In retrospect, it seems a mistake to have included “As many as you want” explicitly on the web version. Instead, maybe they could have allowed a free response for anyone who did not give a numerical answer to the question. It’s too late now for the 2022 GSS, but if you’re asked, “What do you think is the ideal number?”, then, yeah, “As many as you want” seems like a very natural answer to the question–if it is given as an option. If it’s not an option, then it should be clear that the respondent is supposed to supply a number.

There’s more in Cohen’s post–he also looks at time trends broken down by political ideology. Here I just wanted to focus on the measurement issues. It’s an interesting statistical example because measurement problems arise in two separate places: first there’s the interpretation of “ideal number of children for a family to have,” which is not the same as “how many children you would ideally like to have”; second there’s the “As many as you want” response, which got out of control because of carelessness when adapting a face-to-face survey to an online format.