“I think there’s an argument to be made that much meta-scientific work is a kind of mirror image of the empirical work it critiques”

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2025-12-21

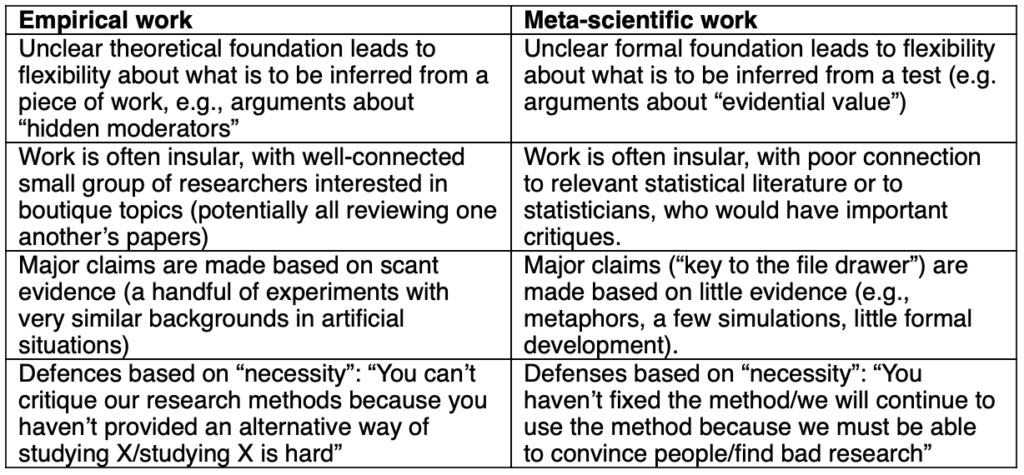

In the context of our recent discussion of the p-curve paper, Richard Morey wrote, “I think there’s an argument to be made that much meta-scientific work is a kind of mirror image of the empirical work it critiques,” and he shared this chart:

I think Morey is on to something here, but, as someone who does a lot of empirical science and a lot of meta-science, I think there’s one big thing he’s missing, one major asymmetry between empirical science and meta-science, and that is that bad empirical science makes strong claims, and the role of meta-science is to question the evidential support behind these claims, not usually to make a positive claim in itself.

The usual pattern goes like this: empirical scientists collect data D, perform analysis A, and use these to make strong general claim X about the world. The meta-scientist then comes along to assess the evidence. A negative meta-science analysis comes to the conclusion that D + A do not provide good evidence for X. The meta-science analysis does not make the strong claim that X is false, let alone the even stronger claim that some preferred alternative Y is true.

This comes up all the time. Some Cornell psychology professor claims to have strong evidence for extra-sensory perception or influence of food labeling on eating or whatever. The meta-scientist comes along and notes irregularities with the data or analysis and provides an alternative story of how these apparently convincing patterns in data could have come to be. The conclusion of the meta-scientific report is not that ESP or large effects of food labels don’t exist but rather that the published record does not provide good evidence of these extraordinary claims. (And indeed the claims are extraordinary, which is how they got so much publicity in the first place.)

It’s the all-important distinction between truth and evidence. I know that Morey understands this distinction and I’m not saying that anything in his above chart is wrong; I’m just trying to put it in the larger perspective of scientific inquiry.

In discussing the above asymmetry between empirical science and meta-science, I’m not saying that meta-science is better. Meta-science is fundamentally parasitic on empirical science, and, sure, empirical science is associated with bold claims, but it’s through making bold leaps–and being willing to retract those leaps as needed–that we make progress. The problem with bad science is not so much the overconfident conjectures–such steps may be psychologically necessary–so much as the unwillingness to reflect on contrary evidence, the unwillingness to admit error, and the practice of not confronting past mistakes.

And also the really stupid things that people say and never apologize for.