Uh oh prediction markets

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2026-01-07

Palko points to this post from Molly White, who writes:

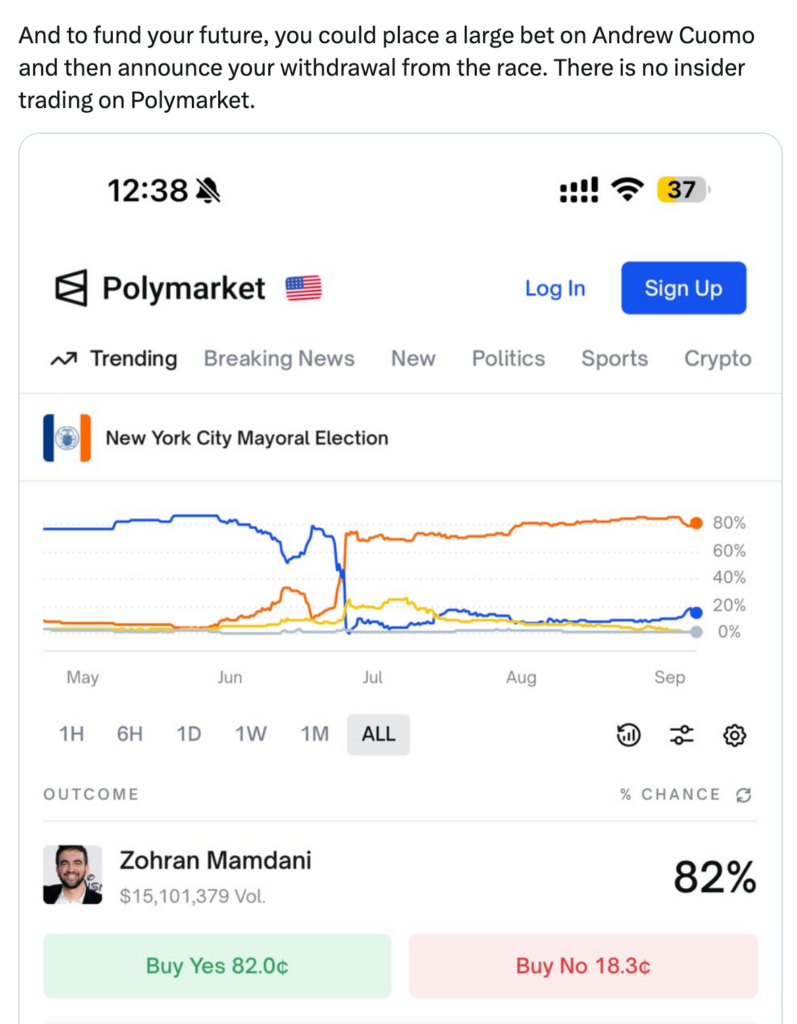

When billionaire Bill Ackman suggested on Twitter that Eric Adams could “place a large [Polymarket] bet on Andrew Cuomo and then announce [his] withdrawal” from the New York City mayoral race, he described something that feels profoundly illegal. A politician profiting from non-public knowledge of their own withdrawal from an election surely crosses some line — insider trading? Market manipulation? Election interference? Illegal gambling? Ackman ended his tweet: “There is no insider trading on Polymarket” — not because it doesn’t happen, but because it won’t be charged. He’s right: the Securities and Exchange Commission’s insider trading rules don’t apply here. But that leaves the question: what rules, if any, do?

As Ackman says, prediction markets fall outside the SEC’s jurisdiction,a living in a different regulatory world than stock markets where executives get prosecuted for trading on non-public earnings or tipping off friends about upcoming mergers. . . .

White continues:

Prediction markets — platforms where people trade contracts that pay out based on whether specific events happen — have enjoyed a surge in popularity over the last few years as they’ve dramatically expanded their operations in the United States. While they have existed for decades, they were long confined to strictly academic exercises — operating as small-scale non-profits that carefully constrained their operations to avoid running afoul of the CFTC. . . .

In 2020, the US-based Polymarket began allowing customers to use cryptocurrency to trade events contracts, though they made no effort to certify their contracts with the CFTC. In 2021, Kalshi emerged as the first fully regulated prediction market in the US, following a hard-won CFTC approval. . . . The CFTC cracked down on prediction markets in 2022. . . . when a district court ruled in Kalshi’s favor in 2024, the company swiftly reinstated the contested markets. The regulatory landscape shifted further after Trump took office. . . .

Finally:

Though prediction markets aren’t a new phenomenon, their growing accessibility to retail traders is. . . . The CFTC has yet to bring any enforcement actions pertaining to market manipulation on events contracts, and it’s not clear they have much appetite to begin doing so.

Other industries that deal with outcome-based bets, like sports wagering, have evolved robust integrity systems both to protect consumers and to preserve trust in the games themselves. . . . Today, sports betting platforms work to screen out athletes, referees, and sports program employees to ensure they’re not betting on games they could potentially influence, and employ monitoring programs to detect suspicious bets. . . .

While Kalshi imposes strict trading restrictions on its presidential election market — barring politicians, campaign staff, pollsters, election officials, and foreign nationals — many of its other markets lack any such prohibitions. This includes election-related markets identical to the type of bet Ackman suggested Adams could place on Polymarket about his own mayoral campaign withdrawal.

Polymarket, which does not yet serve US customers, does no such screening. The platform merely asks users to self-certify they aren’t US-based, with additional basic geofencing that users regularly circumvent. . . .

White summarizes:

Without much oversight, these markets are ripe for manipulation. The gambling-like nature of many markets, combined with limited addiction prevention programs, likely puts vulnerable users at risk. And election markets create concerning new financial incentives that could further corrupt democratic processes.

This does seem like a serious concern.

At one level, this is a problem that should cure itself, in that a few high-profile cases of manipulation should be enough to drive any serious bettors out of the market, so that it just becomes something more like a game of poker than anything else, and the total dollars in the market would not be enough for anyone to make much money by throwing an election, or a sporting event. On the other hand, lots of bad things could happen in sports and politics on the way to this eventual equilibrium. Also, in the absence of serious regulation, we should not underestimate the abilities of cheaters and scammers to come up with new clever means of corruption. So, yeah, I feel like we should be worried.

Another take

Along similar lines, here’s a related post, Prediction markets and the need for “dumb money” as well as “smart money” where I discuss similar ideas that were presented by people who are more politically conservative–they’re less concerned about market manipulation and more concerned that the prediction markets will fall apart on their own.

It’s interesting to juxtapose these two different, but related, lines of criticisms of prediction markets, with one set of criticisms coming from the left and the other coming from the right.

Difference from sports

The post linked just above discusses various differences between news-based prediction markets and sports betting.

Relevant to the NYC mayoral race discussion, one difference is that, in sports, throwing a game to win a bet is one of the main ways that corruption can enter the system. If there is no betting, it’s much harder to have any motivation to throw a game. In contrast, in politics there are lots of ways to benefit from dropping out, especially in today’s political environment where the national government is pretty openly dropping prosecutions of political allies or threatening political opponents. As we discussed in this game-theory-heavy post, there are lots of ways that Adams could corruptly benefit from strategically dropping out, and indeed these are methods that could be both easier and more lucrative than trying to manipulate betting markets. Indeed, if the government doesn’t want to offer Adams some position for which he is unqualified, Bill Ackman himself could just hire Adams for some no-show job in his organization at a salary of a million dollars a year, no?

So, given everything that’s been talked about in the mayoral election so far, it doesn’t seem that prediction markets represent much of a change to the moral, financial, and political calculations of corrupt maneuvering in a political race. It still seems disturbing, though, in the same way that it’s disturbing when politicians decide that various sleazy activities, which in the past they would have tried to hide, are now done in the open. And also disturbing in the potential pollution of the signal offered by prediction markets themselves.