What is “workflow” and why is it important?

Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science 2026-01-08

A few years ago we decided to write a book on Bayesian workflow, and we got ready for it by writing this article, which begins as follows:

The idea was the traditional framing of statistical inference was too narrow, in that it treated the statistical model as given, without capturing the real-world practices of building, evaluating, improving, and understanding models. Methods such as predictive checking, exploratory data analysis, and sensitivity analysis, are important steps in data analysis without being part of inference. We use the term “workflow” to represent our larger process of data analysis. An extended workflow would also include pre-data design of data collection and measurement and after-inference decision making, but in our article and book on Bayesian workflow we focus on modeling existing data.

“Workflow” has different meanings in different contexts. We have been influenced by the ideas about workflow in computing that are in the air, including statistical developments such as the tidyverse which are not particularly Bayesian but have a similar feel of experiential learning. Many recent developments in machine learning have a similar plug-and-play feel: they are easy to use, easy to experiment with, and users have the healthy sense that fitting a model is a way of learning something from the data without representing a commitment to some probability model or set of statistical assumptions.

In our paper we supply some background:

We can also connect to general ideas of building, checking, and expanding statistical models, as expressed by Tukey (1977), Box (1980), and Jaynes (1983). Or, from another direction, we can look up “workflow” on wikipedia, which says:

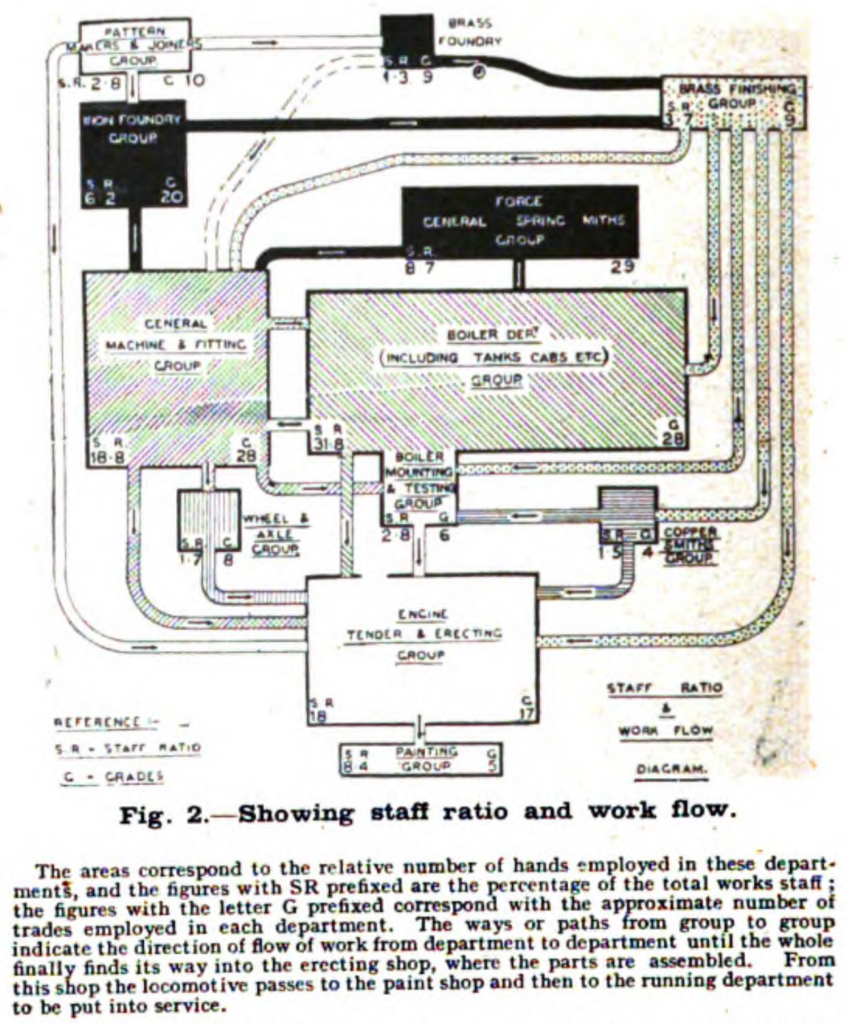

Workflow is a generic term for orchestrated and repeatable patterns of activity, enabled by the systematic organization of resources into processes that transform materials, provide services, or process information. It can be depicted as a sequence of operations, the work of a person or group, the work of an organization of staff, or one or more simple or complex mechanisms. . . . The modern history of workflows can be traced to Frederick Taylor and Henry Gantt, although the term “workflow” was not in use as such during their lifetimes. One of the earliest instances of the term “work flow” was in a railway engineering journal from 1921.

Here’s the relevant bit from the 1921 citation:

We and other statisticians have used the term “workflow” to encompass the various steps of data processing and analysis that we use to make our work scientifically replicable, both in the direct sense of providing all necessary practical details so that the computations can be reproduced, and in the larger sense of fitting models and applying procedures that are appropriate to the data at hand and to the questions being asked.

All of this is important for (at least) three reasons:

1. Practical workflow includes all sorts of things that aren’t written down, or are scattered across various sources. It’s good to document what we are doing.

2. Once these steps are written in some sort of organized way, this can help future researchers be more systematic in their data analysis. We would not expect every workflow tool to be used in every data analysis; the point is to make these tools more available, through explanations, examples, and software.

3. Future research should be benefit from a clearer exposition of present best practices. Theoretical statistics is the theory of applied statistics, and so it’s good to know what is being done, to expand the boundaries of theoretical investigation, which eventually should result in improved methods.

Also, data analysis workflow is closely related to ideas in computing workflow such as version control, testing, readability, and maintainability of code. Software is written collaboratively and to be used in a variety of contexts by a range of users; similarly, statistical methods build upon multiple contributors and, once released, get used in the wild in various unexpected ways. So there’s a connection between the workflow involved in developing a method or writing software, and the workflow of the later users of the method or software.