The New Digital Divide

Messy Matters 2013-03-15

In the 15 years since Hoffman and Novak highlighted the digital divide between those with and without internet access, use of the web has risen dramatically in the United States, increasing from roughly 30% to 80% of adults regularly going online.[1]Even with this tremendous growth in access, however, substantial inequalities persist across demographic groups. For example, in contrast to the 80% of adults in the general population who use the internet, only about 70% of Blacks and 40% of people over 65 do so.Assessments and discussions of the digital divide typically focus on these disparities in basic access. In a recent paper with Jake Hofman and Irmak Sirer, we investigate a related but distinct question: Among those individuals who are already online, how do usage patterns vary across the population?

Our analysis of web browsing behavior is based on complete activity logs for approximately 250,000 people in the Nielsen MegaPanel, who in aggregate generated over three billion pageviews over the course of a year.In addition to these web browsing histories, individual and household-level data were collected from each panelist, including age, sex, race, educational attainment, and household income.Leveraging these data, we were thus able to systematically investigate online browsing behavior at scale across a representative sample of the online population.

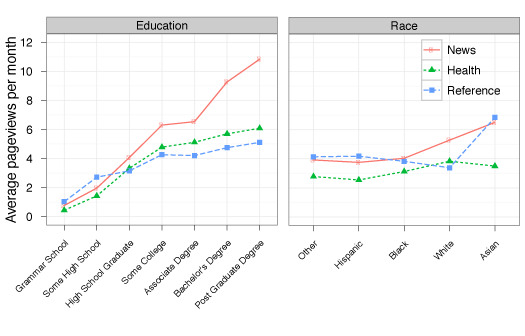

“Adults with a post-graduate degree spend more than three times as much time on health sites than those with only some high school education, and Asians read more than 50% more online news than Blacks and Hispanics.”

Concern over the digital divide typically stems from the belief that internet access improves quality of life along several core dimensions, including health and education, and that lack of access thus leaves certain subpopulations at a disadvantage. We examine usage in three areas that directly relate to these particularly consequential outcomes — news, health (e.g., WebMD), and reference (e.g., Wikipedia) — and find large differences across demographic groups. Adults with a post-graduate degree, for example, spend more than three times as much time on health sites than those with only some high school education, and Asians read more than 50% more online news than Blacks and Hispanics, exacerbating disparities in basic access between these groups.On the other hand, differences between Whites and underrepresented minorities largely vanish among those who are already online.

These results illustrate that the digital divide is more than a simple question of access, and highlight some of the issues that remain even among those with access to the web.In many ways, however, our findings raise as many questions as they answer. Perhaps most importantly, what are the effects of these observed differences in web browsing behavior? While it is certainly reasonable that easier access to information on, for example, nutrition and contraception would lead to better health outcomes, rigorously establishing this relationship is not easy.In this regard, accurately measuring online behavior is an important, but still just a first step in making informed policy decisions.

Footnotes

[1] These and related data are available from the Pew Research Center.

Illustration by Kelly Savage. Big thanks to Mainak Mazumdar and the Nielsen Companyfor providing the web panel data. Large chunks of this post were shamelessly plagiarized from my paper with Jake Hofman and Irmak Sirer, “Who Does What on the Web: A Large-scale Study of Browsing Behavior”.