A few years ago Morgan Stanley released an analysis promising that the metaverse would soon be worth more than $5 trillion dollars. Their latest one on humanoid robots may not rise to that level of prescience.

West Coast Stat Views (on Observational Epidemiology and more) 2025-05-06

Guys, we've been pointing out bubbles here at the blog for well over a decade now and, trust me, this is a bubble Just as it did in response to the metaverse hype of a few years ago, Morgan Stanley has jumped on the humanoid robot bandwagon with a report predicting:

Based on our analysis, we believe ~75% of occupations and ~40% of employees in the US have some degree of "humanoidability." This amounts to an estimated addressable market of ~$3 trillion, or ~63 million humanoid units in the US alone. While this estimate considers only the US, we note that a TAM based on the global labor market could be greater by multitudes of magnitude.

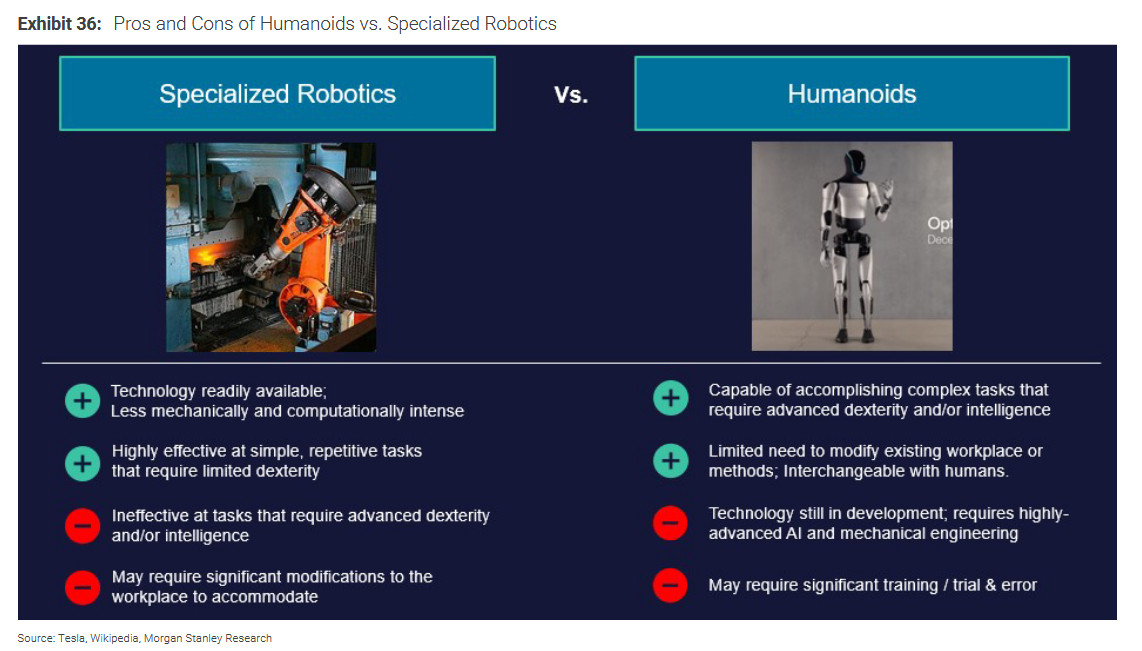

The analysis rests almost entirely on conflation, omission, and insane amounts of techno-optimism. The current capabilities of these machines are grossly exaggerated. Their likely costs are absurdly lowballed. The potential market size is substantially overstated. Alternative robotic approaches that would be undeniably more efficient, productive, and cheaper are virtually ignored altogether.

The eighty-six report has one paragraph on why multi-purpose robots should characters from I, Robot which mainly boils down to the Cylon Design Fallacy.

Why humanoids? Many investors reading this report will ask the question “why do we need robots shaped like humans?” There are indeed strong arguments for robotics to take many highly specialized forms (robot arms, snake-shaped robots, robot dogs, robotic dust and as many form factors as you can imagine). However, many robot and AI experts say the strongest argument for robots in a human form factor is that in a world already created for humans, the environment is already "brownfielded" for humanoids. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang recently stated “The easiest robot to adapt into the world are humanoid robots because we built the world for us. We also have the most amount of data to train these robots than other types of robots because we have the same physique." Additionally, think of the great variety of tasks that humans are able to perform with our bare hands or using tools and the multitude of machines designed for human hands and fingers.

Notice the -- if you'll pardon the phrase -- sleight of hand here. There's no reason a robot with 5-fingered hands with opposable thumbs needs to be otherwise humanoid. Being bipedal is arguably the main driver of cost and complexity but it barely figures it all in the only reasons they give for going with the humanoid design.

As we've discussed before, the bipedal humanoid design has lots of problems. It is needlessly complex and expensive, bringing virtually no added functionality in most situations. It's unstable—even those impressive Boston Dynamics demonstrations have to edit out the scenes where the robot falls over. In addition to the daunting engineering challenges of building a robot that walks on two legs, there's also the issue of a top-heavy design, since the battery is generally stored in the torso. This places the center of gravity three to four times higher than what you get with more traditional wheeled-base designs. Worse still, having the batteries relatively inaccessible means these robots must be taken offline for substantial periods just to recharge—compared to more traditional designs, which often allow for fast and easy battery swaps. It's remarkably difficult to make a compelling case for bipedal locomotion in robots, and the arguments presented barely address the elephant in the room. In particular, the "training" argument applies mostly to arms and hands. Outside of a few isolated applications, if you replace the legs with wheels, you get a cheaper, more efficient, more stable, and more reliable machine—one that also has the added benefit of being able to operate virtually 24/7.

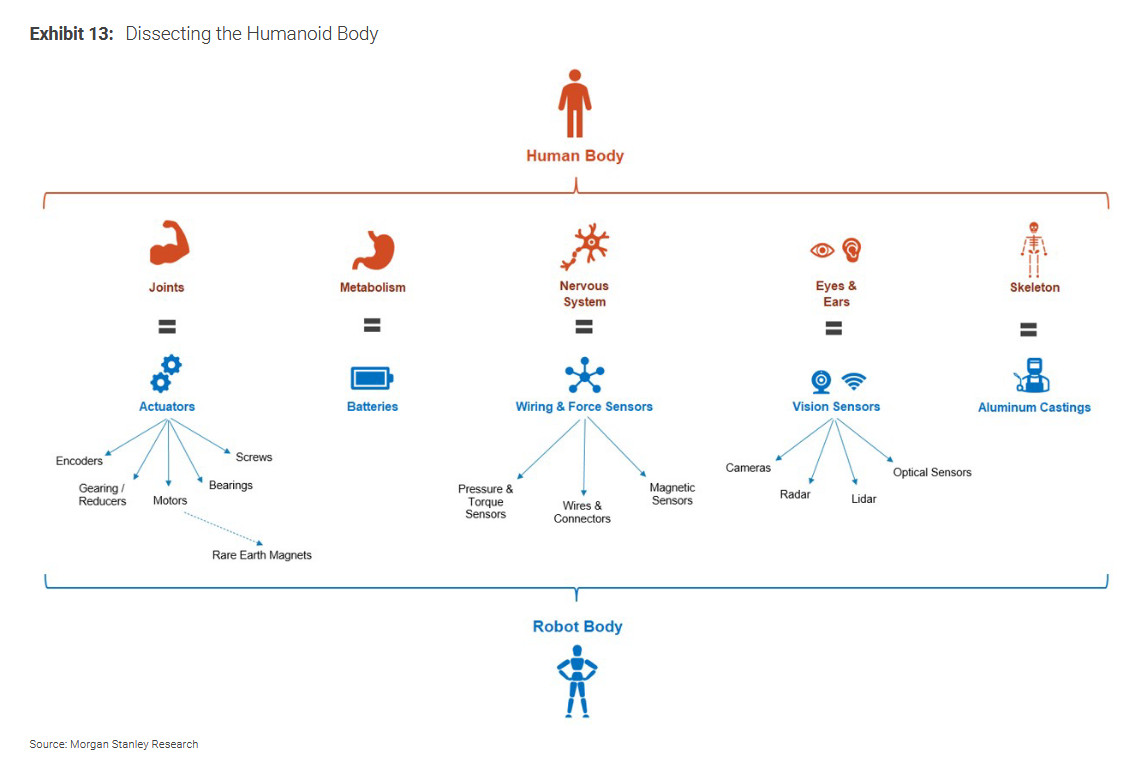

The authors lean heavily on the biomimicry throughout the report.

Along similar lines, note how Morgan Stanley equates "humanoid" with "general purpose."

This is a huge misrepresentation of the state of robotics. There is no reason whatsoever that a general-purpose or multi-purpose robot needs to be humanoid. If anything, it is in many ways a particularly poor design choice due to its instability, its complexity and cost, and the limitations imposed by naive biomimicry. The design has no innate advantages in performing complex tasks or demonstrating dexterity. If anything, the previously mentioned instability puts it at a disadvantage when it comes to delicate work.These are incredibly thin arguments if you're trying to defend design choices determining a multi-trillion-dollar shift in the economy that would replace a large portion of the workforce. I suspect that, on some level, the people making these arguments realize how unconvincing they are—which might be why they're never prominently featured in these analyses and articles. You have to dig quite a ways into this massive document before you reach the one and only paragraph justifying the humanoid design. But of course, that's not the real reason. These robots look the way they do because it seems cool and futuristic—like something out of a science fiction movie. From a serious business standpoint, those reasons are indefensible. But if your primary objective is to build a hype bubble, they make perfect sense.

In case you think I'm being unfair about the sci-fi crack:

And, of course, Elon is cited.

One billion humanoid robots by the 2040s? Tesla CEO Elon Musk has been increasingly focused on Optimus (Palo Alto engineering center) in recent months, per his comments. Tesla first unveiled its humanoid robot, Optimus, on September 30, 2022. The bipedal robot included 28 actuators in two categories: 1) rotary actuators, consisting of harmonic reducers, ball bearings and sensors, for rotating motions such as shoulders and elbows; 2) linear actuators, comprising planetary rollers, ball bearings and sensors for linear motions like human muscles. Twelve actuators for two hands. Many more details have been kept internally at the company. In January of this year, Elon Musk said he expected to see over 1 billion humanoid robots in operation by the 2040s. At Tesla's June 13th 2024 annual shareholder meeting, Mr. Musk stated he expects to have at least 1,000 Optimus robots working at Tesla next year, and that "things are gonna scale up very rapidly from there." In the same meeting, Mr. Musk expressed his confidence that humanoid robots will eventually outnumber human beings and "probably be 20 billion or more" (no timeline shared).

In case you're new here, Musk has predicted a million Tesla robotaxis on the road "next year" every year since 2019 and predicted SpaceX would make its first Mars landing in 2022.