We haven't talked about SpaceX lately

West Coast Stat Views (on Observational Epidemiology and more) 2025-06-23

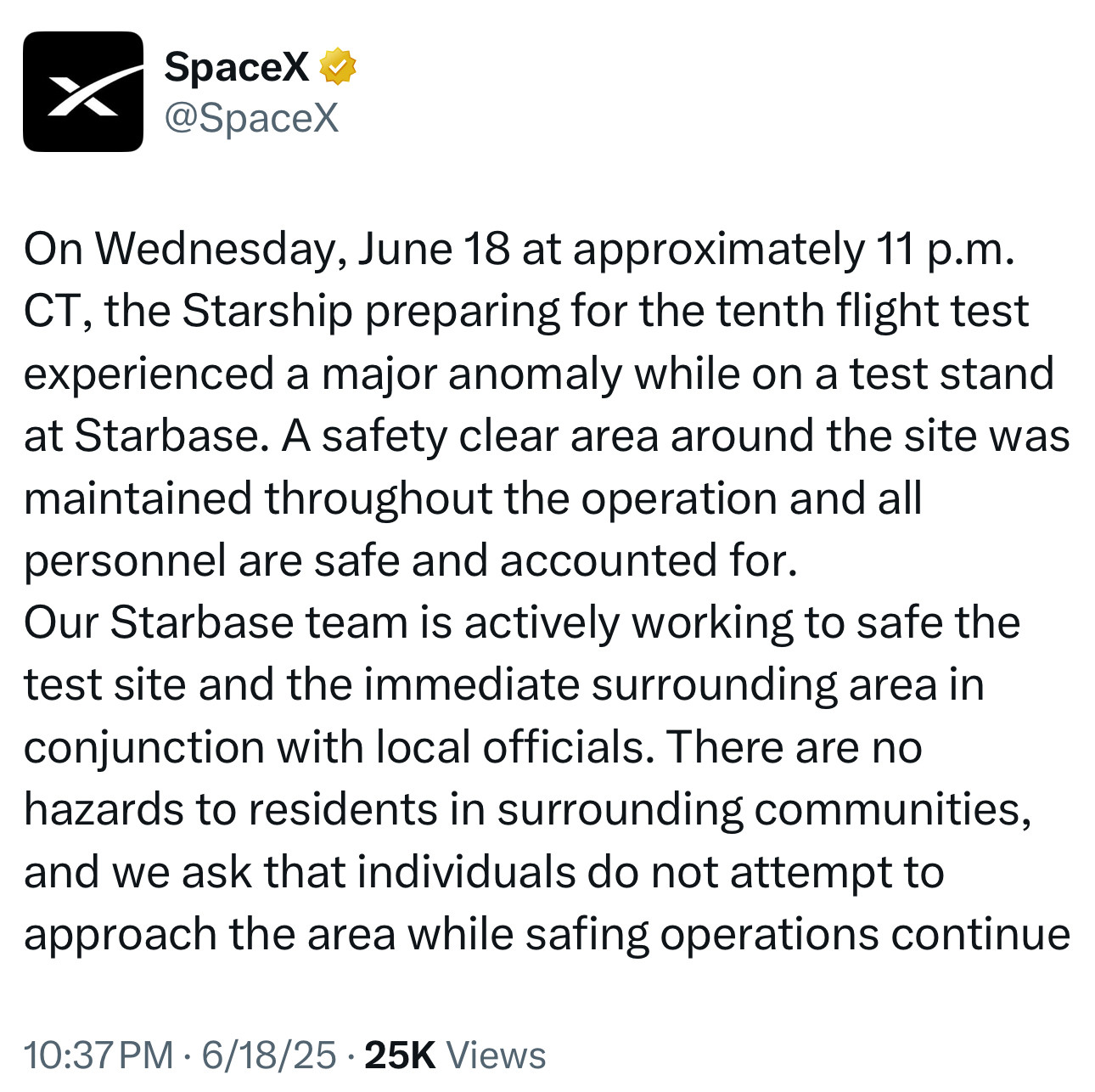

Important note: there would be about 50x as much fuel loaded for a fully stacked launch on the pad, and that SpaceX repeatedly downplayed the chances and size of an on pad failure in order to categorize the project as "insignificant" under NEPA and that @petebuttigieg.bsky.social helped them do this [image or embed]

— Rude Law Dog (@esghound.com) June 18, 2025 at 10:51 PM

The consequences of actions like these are real, environmental groups say. SpaceX’s launch site is surrounded by a state park and federal wildlife refuge home to hundreds of of thousands of shorebirds, sea turtles and other species. Biologists say the company’s Starship launches are having a measurable impact. A recent report documented how SpaceX’s last launch destroyed nests of a vulnerable population of shorebirdsThat's a high price to pay for a type of launch vehicle that's looking more and more like a dead end. More than two weeks before the latest explosion, engineer turned journalist Will Lockett wrote a withering post on the state of the program.

Okay, but I can already hear the Musk fans pearl-clutching and screaming, “We learn from failure!” Fair enough. Let’s look at the lessons we can glean from these results.

Firstly, why did SpaceX try a new landing path for Super Heavy, even though they have successfully landed it multiple times? Well, weight. Starship weighs far too much, meaning its possible payload is vanishingly small, and its engines are being overstressed (hence the constant engine failures). SpaceX must make Starship lighter for it to even have a chance of being functional. The heaviest component of a rocket, particularly a self-landing one, is fuel. In fact, there is a double weight-saving opportunity there, but we don’t have time to go into that today. Super Heavy Booster’s previous landing relied almost entirely on retrorockets, making it predictable but incredibly fuel-hungry. This new path attempted to replace the bulk of that fuel requirement with atmospheric drag by allowing the rocket to fall to Earth in a belly flop position, which is far less predictable but much more fuel-efficient. This reduced the fuel requirement and caused the rocket to be significantly lighter.

That was, until the rocket broke up, meaning that it could not handle the stress of this belly flop manoeuvre. Furthermore, it broke apart after its retrorockets reignited, which also suggests that they may have failed, implying that these engines might be pushed too hard to be reliably reused. So the lesson we can take away from this teachable moment is that Super Heavy Booster and its engines need to be heavily reinforced to survive such a landing (especially if it is to be reused, as planned), but doing so would add enough weight to render the entire exercise moot. So, really, the lesson here is that you meet a dead end when you try to make the first stage lighter.

...SpaceX still has a long way to go before Starship becomes a viable launch vehicle. It still has to successfully land the upper stage, reuse an upper stage, reach orbit, deliver a payload to orbit, reach a useable payload capacity, conduct a cryogenic fuel transfer between two starships in space (which has never been done before), perform a successful long-duration flight test, conduct a successful uncrewed lunar landing and conduct a crewed lunar landing. All of which, for context, was meant to be achieved by January 2025! Nearly all of Starship’s paid contracts are for human spaceflight to the Moon, which requires repeated orbital refuelling and human spaceflight certification. Orbit refuelling is incredibly difficult, and in order to become human spaceflight certified, SpaceX needs to prove that they can successfully land the upper stage almost 100% of the time. It has taken them nine failed attempts and almost $10 billion for Starship to not reach orbit with a fraction of its promised payload and to never land an upper stage or successfully reuse a first stage. How many test flights, dollars and years will it take to actually get this hunk of junk working?

I know I always say this, but it is an important comparison. After nine launches, Saturn V only had one partial, non-destructive failure and had taken three crews to the lunar surface. Sure, it was a less complex rocket than Starship, but NASA achieved this using technology from the 1960s that was much less reliable and accurate. However, here’s the thing: Musk is currently claiming that Starship will somehow reach a payload of 45 tonnes (which is three times what Flight 9 failed to deliver to orbit and less than half of what was promised). That means a lunar starship would need refuelling 33 times in orbit before it can go to the Moon. Even if we assume Starship can be fully reused, that would put the price of a Starship lunar launch at $2.38 billion. Yet, the Saturn V launched 50 tonnes to the Moon for only $1.8 billion in today’s dollars, and that includes development costs spread over its 13 launches (read more here).

Recently, Musk has been talking about skipping the moon and focusing on Mars. As far as I can tell, he has not, however, been talking about giving back the money he took for Artemis.