"Back in my day, the internet was really something."

West Coast Stat Views (on Observational Epidemiology and more) 2025-10-30

The fundamental challenge of the internet has always been a variation on the old Steven Wright line: “You can’t have everything. Where would you put it?” Or, in this case—how would you find it? Given the vast quantity of content, how do you connect users with what they're looking for? Even when things were working as they were supposed to, this was an increasingly daunting problem: ever-growing content, link rot, and even before AI slop, content farms flooding algorithms with SEO-optimized garbage. Add Sora and ChatGPT to the mix, and you have a scenario where the good new content (and yes, it’s still flowing in) is lost in a tidal wave of crap. This might not be so bad if the gatekeepers were stepping up to the moment, but instead we’re seeing the opposite. Alphabet’s Google—and in particular YouTube—turn a blind eye to content farms that violate their standards and even endanger their audience (such as recommending a fun kids' activity involving using plastic straws to blow bubbles in molten sugar). [Even if you have no interest in cooking, you should check out all of food scientist Ann Reardon’s debunking videos.]

5-min crafts DESTROYED my microwave!

They aggressively push AI slop even when no one seems to be clicking. (I have no idea why the algorithm thinks I would be interested in any of these but my feed is full of them.)

Worse yet, search functions on major platforms are declining in both functionality and quality. From Matthew Hughes’ highly recommended What We Lost

Worse yet, search functions on major platforms are declining in both functionality and quality. From Matthew Hughes’ highly recommended What We Lost

Allow me to confess something that will, for many of the readers of this newsletter, make me seem immediately uncool. I like hashtags.

I like hashtags because they act as an informal taxonomy of the Internet, making it easier to aggregate and identify content pertaining to specific moments or themes. In a world where billions of people are posting and uploading, hashtags act as a useful tool for researchers and journalists alike. And that’s without mentioning the other non-media uses of hashtags — like events, activism, or simply as a tool for small businesses to reach out to potential customers.

You see where this is going. A few years ago, Instagram killed the hashtag by preventing users from sorting them by date. In its place, Instagram would show an algorithmically-curated selection of posts that weren’t rooted in any given moment in time. It might put a post from 2017 next to one from the previous day.

What happens if you just scroll through and try to look at every post with the hashtag, hoping to see the most recent posts through sheer brute force? Ha, no.

Instagram will, eventually, stop showing new posts. On any hashtag with tens of thousands of posts, you’ll likely only see a small fraction of them — and that’s by design. Or, said another way, Instagram is directly burying content that users explicitly state that they wish to see. Essentially, your visibility into a particular hashtag is limited to what Instagram will allow.

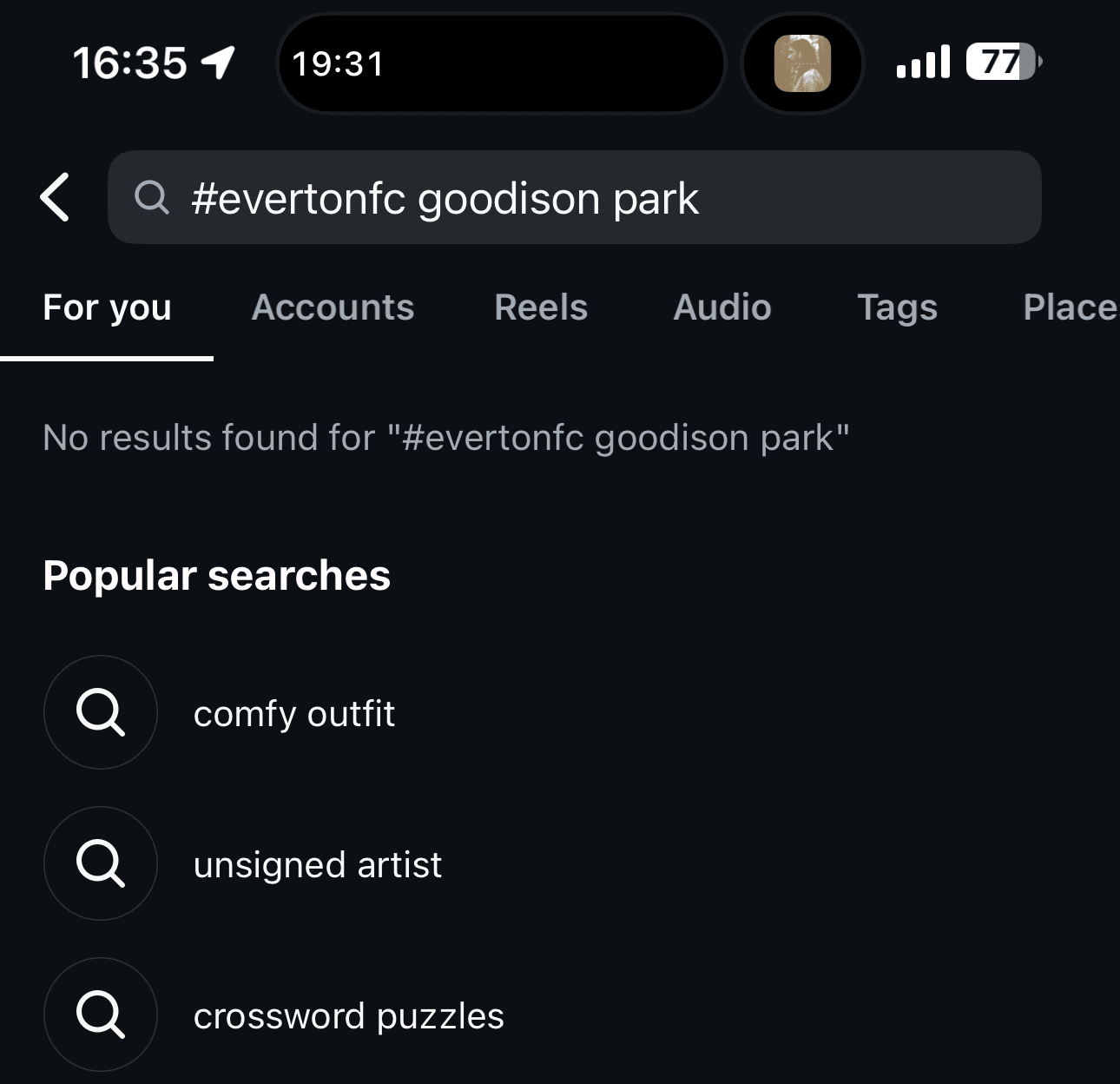

Additionally, users can’t refine their search by adding an additional term to a hashtag. If you type in “#EvertonFC Goodison Park,” it’ll reply with “no results found.”

Premier League, and Goodison Park is the stadium it used until this year. There should be thousands of posts that include these terms. It’s like searching for “#NYYankees Yankee Stadium” — something that you’d assume, with good reason, to have mountains of photos and videos attached to it.

Additionally, when you search for a hashtag on Instagram, the app will show you content that doesn’t include the hashtag as exactly written, but has terms that resemble that hashtag. As a result, hashtags are effectively useless as a tool for creating taxonomies of content, or for discoverability.

Most of the points I’ve raised haven’t been covered anywhere — save for the initial announcement that Instagram would be discontinuing the ability to organize hashtags by date. And even when that point was mentioned, it was reported as straight news, with no questioning as to whether Instagram might have an incentive to destroy hashtags, or whether the points that Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri would later make (that hashtags were a major vector for “problematic” content) were true.

When Moseri would later say that hashtags didn’t actually help drive discoverability or engagement, that too was repeated unquestionably by a media that, when it comes to the tech industry, is all too content to act as stenographers rather than inquisitors. It’s a point that’s easily challenged by looking at the Instagram subreddit, where there are no shortage of people saying that the changes to hashtags had an adverse impact on their businesses, or their ability to find content from smaller creators.

We should probably talk about the decline of Google search at this point but that needs a post of its own.