How to Make PBL a Reality in a Distance Learning Environment

Education Rethink 2020-04-15

If you think about your most powerful learning experiences, there’s a good chance at least one of these experiences involved a project. This is where you learned how to research, how to ideate, how to work with others, how to engage in productive struggle, and how to revise your work. These epic projects were what built those life-long soft skills that you use on a regular basis.

And yet, these PBL experiences typically take place in a physical environment, where students can collaborate together and you, as the facilitator, can pull small groups and monitor project progress. But right now, there are many classrooms that aren’t in a classroom at all. Teachers are suddenly shifting toward virtual and online modes. So, how do we do PBL in a distance learning environment?

I want to point out ahead of time that there is no instruction manual for this. We are all learning how to do this emergency distance learning thing together. But there are some big ideas that I would like to share. Hopefully, there’s something helpful for you here.

Listen to the Podcast

If you enjoy this blog but you’d like to listen to it on the go, just click on the audio below or subscribe via iTunes/Apple Podcasts (ideal for iOS users) or Google Play and Stitcher (ideal for Android users).

http://www.spencerauthor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PBL-Social-Distance.mp3

Seven Key Ideas for Making PBL a Reality in Distance Learning

The following are some things you might want to consider as you attempt PBL in a distance learning setting.

1. Make PBL optional

I’ve written before about why every student deserves access to meaningful projects. I love the way PBL empowers students and helps develop critical soft skills that they will use for the rest of their lives. However, authentic PBL requires a significant amount of executive function and metacognition. At times, it can stretch students, in terms of problem-solving productive struggle. During a typical school year, you can provide necessary accommodations for students who struggle with executive function. You can integrate social-emotional learning into your units as they experience the creative struggle. Unfortunately, this is not a typical school year. Right now, amid all the uncertainty, some students might want something more traditional. They might want to do packets and worksheets. They might want to see their progress in a more concrete way. And that’s okay. This is an idea I explored in my latest video:

For this reason, I would provide options for students. If you have access to book work, handouts, or packets, allow students to opt out of the project and choose the more traditional assignment instead. This doesn’t mean that PBL isn’t for them. It simply isn’t for them right now. By giving students the option between a project and a packet, you’re actually honoring their agency as a learner. You’re saying, “these are chaotic and unpredictable times but I’m going to give you some control over what type of learning you need right now.”

2. Take PBL away from the screen.

If you walk into a PBL classroom, there’s a good chance that you’ll see movement and conversations. You might even see hands-on learning, with tools and physical materials. Now shift toward distance learning. Chances are you’ll see students working alone in front of a laptop or a tablet. However, distance learning doesn’t have to mean spending hours in front of a screen. Students can still do hands-on prototyping and engage in movement as they work on projects at home. In many cases, the physical environment might even allow for more movement than a typical classroom, where you have a small space and tons of furniture.

Here are a couple of ideas to make this happen:

- Schedule project time that will be on-screen and off-screen. In other words, you can meet your whole class for a virtual hang out where you do a class meeting and debrief project goals and progress (similar to a standing meeting) but then “send them off” to work on something physical and hands-on.

- Ask students to find supplies and work within the creative constraint to design something new. Sometimes, duct tape and cardboard are the best options for boosting creative thinking. We used to do pinball machine projects where students brought in random items from home, along with cardboard and duct tape. You can take the same approach here.

- Have students do hands-on learning but also use their smart phone for synchronous communication. They can text, Facetime, or make phone calls. If your students are older, they might use WhatsApp or Voxer. If they’re younger, they might stay on a small group video conference. But the idea is that the communication tool is on in the background, giving a sense of proximity while the work is being done in a physical, hands-on way.

- You can create projects that blend together the lo-fi and the high-tech.

This last idea is at the heart of vintage innovation, a theme I explore in my latest book. Here’s an overview of the concept:

Vintage innovation happens when we use old ideas and tools to transform the present. Think of it as a mash-up. It’s not a rejection of new tools or new ideas. Instead, it’s a reminder that sometimes the best way to move forward is to look backward. Like all innovation, vintage innovation is disruptive. But it’s disruptive by pulling us out of present tense and into something more timeless. Vintage Innovation is a both/and mindset. It’s the overlap of the “tried and true” and the “never tried.” It’s a mash-up of cutting edge tech and old school tools. It’s the overlap of timeless skills in new contexts. Vintage innovation is what happens when engineers use origami to design new spacecraft and robotics engineers are studying nature for innovative designs.

Distance learning is the perfect time for vintage innovation. As a teacher, it’s what happens when you do sketch-note videos mashing up hand-drawn sketches with digital tools. Here’s an example of this mash-up concept:

I mention this because I keep hearing folks ask, “How do I get my class online?” But a different, perhaps more relevant question, might be, “How do we help students learn from home? What should learning look like in these times? And how do we continue to create a culture of creativity despite the physical distance between us?” Often, this involves using physical items and incorporating movement into the process.

3. Be strategic with grouping

We’ve all had times when group work failed. Perhaps you missed deadlines, failed to communicate, and didn’t learn from mistakes. But chances are, you’ve also been part of a team where you accomplished something epic together that you could have never done on your own. In these moments, the group work doesn’t even seem like work.

At the same time, we also know that groups can get dysfunctional. You can have moments when one member does all the work and other members do nothing. Other times, group members get into huge arguments and simply can’t get along. This is why I recommend providing grouping options. Allow students to decide between individual, partner, or small group projects. You can vary the requirements according to the grouping. I’d also allow students to work with friends. True, they might goof off and socialize. Then again, they’re in social isolation. Maybe a little goofing off is what they need right now.

At the same time, we also know that groups can get dysfunctional. You can have moments when one member does all the work and other members do nothing. Other times, group members get into huge arguments and simply can’t get along. This is why I recommend providing grouping options. Allow students to decide between individual, partner, or small group projects. You can vary the requirements according to the grouping. I’d also allow students to work with friends. True, they might goof off and socialize. Then again, they’re in social isolation. Maybe a little goofing off is what they need right now.

If students are working collaboratively, there are a few ways to improve the collaborative process:

It helps to build interdpendency into group structures.

If independent learning is fully autonomous and dependent learning involves students simply depending on another person, interdependence is the overlap, where students have autonomy but they must have mutual dependence on one another.

When students work interdependently, each member is adding value to the group project. Each member has something of value to add to the group. So, what does this look like? One example is the following brainstorming strategy. Notice that students must listen to one another depend on each other for new ideas. Even the “low” student has something valuable to add to the group. This is a core idea of interdependence. Each member has something valuable to add. A distance learning variation is to have students submit their ideas on a shared Google Form and then analyze the spreadsheet afterward:

Similarly, when doing research, every student can add additional information to the group’s shared knowledge. They can read articles online or listen to podcasts that are varying reading levels and interest levels and then share what they learn during an interdependent research debrief. Students can share their debriefs in a group chat or in a video conference.

In some cases, you might assign roles that correspond to skill levels. When students move from inquiry to research, they often need to narrow down their questions to determine which ones will actually guide the research process. Here’s what the process looks like. See if you can spot the interdependency and differentiation.

- Students generate questions independently. They might need sample questions or sentence stems, but they can all create questions.

- Once they have their questions, they can send them to a Google Document or submit them on a Google Form.

- Students meet up via video conference or on the phone to analyze the questions to see if they are actually research questions. Each member has a role. The first member checks to see if the question is fact-based. The second checks if it is on-topic. The third checks to see if it is specific. The fourth person is the quality control leader.

- Members #1-3 can put a star by each question that fits their criteria. So, member #1 looks at each question and puts a star by questions that are fact-based. Meanwhile, member #4 is available to help and observe. Then member #4 double-checks all the questions with three stars and circles or highlights it if it’s an actual research question.

Note that a struggling student might still be able to do the job of member #1 or 2 while a more advanced student can do #3. Meanwhile, the group member who typically dominates and achieves at a higher academic level learns to trust other members and wait and observe. However, they can still provide expertise as the quality control person who has the final say.

4. Use structures to boost creativity.

Projects tend to fall apart when they are too unstructured. I once made the mistake of saying, “Hey everyone, go create a documentary. Start by planning out your project and then do it.” Nobody planned anything. Nobody did anything. Two days later, I realized we needed some structure. The first type of structure is at the larger macro level. You might want to have phases in a project. They might have an inquiry phase, a research phase, a planning phase, and a creating phase. They might follow the publishing process, the engineering process, the scientific method, or the design thinking process.But the idea is that you’re breaking it into phases.

If you’re interested in design thinking, here’s the LAUNCH process that AJ Juliani and I designed together.

When students have phases in a project, it naturally breaks down the larger project into segments that they can manage. You might even have students engage in their own project management. It also creates natural deadlines. Research has demonstrated that people tend work harder as they approach the end of a task and phases help break it up with natural endings.

You can also employ structures at the micro level. Here, students might use a protocol for brainstorming. They might use a specific process for research. The following is an example of a process for peer feedback:

5. Keep equity at the forefront.

It’s important that we keep equity at the forefront of distance learning PBL. This begins with doing an audit of access. Do your students have access to the internet? Do they have laptops or tablets? Are you planning projects that can include limited materials? Do students have a space to work? There is a huge difference between a large family in a studio apartment and a family in a 3,000 square foot house. But access also involves time and opportunity.

It’s easy to step into digital spaces and forget that they are not socially neutral. The systems that perpetuate injustice off-line exist online as well. With that in mind, I’d like to remind educators to remember the following:

- Not everyone has the same access to technology. Not every student has the same device or the same internet connection. Not every student has the same access to a quiet workspace at home. Please work with key stakeholders to address the issue of equity of access.

- Power dynamics exist online. Pay close attention to the role of gender and race in your online instruction. There’s a tendency for people to assume a false social neutrality online but you need to address power dynamics. Please consider finding experts in culturally responsive pedagogy and ask them for a critique of your online materials so that you can find areas where you need to improve.

- Be sure to provide linguistic support. Please remember that some of your students might not be native English speakers and they deserve access to sentence stems, visuals, front-loaded vocabulary and other accommodations that you provide in-person.

- Embrace a Universal Access and Universal Design mindset. Re-read the IEPs and 504 plans to provide necessary accommodations. Lean in to the special education teachers and disability support staff to think through how you will make your instruction universally accessible. For example, you will need to check that closed captioning is available on all videos and that transcripts are available for podcasts. You might need to provide additional assistive support technology. Often, librarians and instructional designers will have key information for you in these areas.

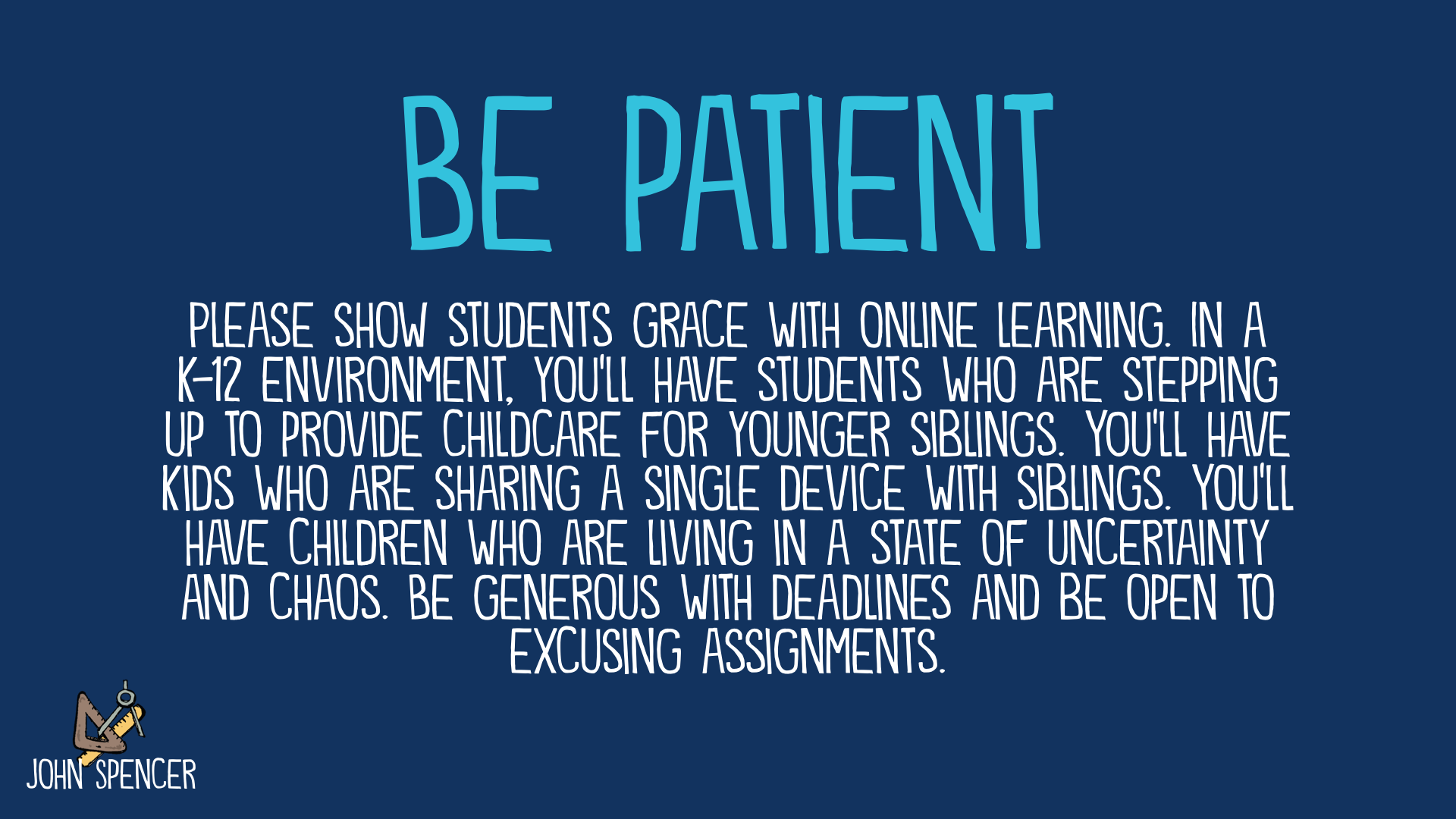

This means we need to provide flexibility with tasks and with grading. We need to allow students to turn things in late. This doesn’t mean we are holding students to a lower standard. It means we modeling empathy.

As a teacher, you might want to create a space for technology tutorials, academic tutorials, and scaffolds like sentence stems. You might also need to send emails or even do one-on-one chats with students who are struggling. Lately, I’ve seen memes mocking students for turning work in late or failing to understand how to upload an assignment on Google Classroom. These snarky memes ask, “you can do SnapChat but can’t do Google Classroom?” but the truth is you never know the whole story. As educators, we need to assume the best and provide students with guidance.

6. Do frequent check-ins.

A check-in can be as simple as an email or as complicated as a video chat. But the idea here is to make your presence known to the group by doing check-ins. One of my favorite options is a Google Form. You can ask students questions about their goals for their project and about their progress. You might ask them to reflect on how their group is working together. You might even ask how they are holding up in this pandemic. I’ve found that it helps to vary the questions with open-ended reflection questions and having Likert scales or checkboxes. Sometimes a “how are you feeling right now?” question feels too overwhelming but a simple checkbox allows students to select their emotions. In other words, “How are you feeling. Check any of the emotions that apply to you right now.”

This can be a challenge given the increased paperwork and communication that teachers are dealing with. It’s important that we don’t beat ourselves up if we aren’t meeting with each group each day. However, a simple email or Google Form can communicate your presence to your students.

7. Start small

You might want to start out small with week-long project. It might be a Geek Out blog, where students choose their own topics, engage in research, and do a blog series.

Or you could do a simple one-day divergent thinking challenge and have students create something entirely new. You could even do a scavenger hunt for random items (something yellow, something flexible, etc.) followed by a divergent thinking challenge:

I created a maker challenge that you can do in a week. A word of caution. Some kids will get really frustrated by this. I had students comment with “I love this!” but also commented with “I hate this! It’s not even possible to do.”

You could also do a Wonder Day project and have students pursue their own questions and find their own answers.

The bottom line is that a smaller, week-long project might just be the best way to kick off PBL in a distance learning environment.

For some students, doing an authentic project will not only build soft skills, it will also be a part of what gets them through this time of isolation and a part of what makes you that teacher they remember forever.

How to Get Started with PBL

We’re all on a PBL journey, whether you’ve been using a PBL approach for decades or you just launched your first project this semester. If you’re interested in getting started, I have a toolkit and an eBook that you can download for free. Check it out below.

Get Your Free PBL Toolbox

Get this free toolbox along with, members-only access to my latest blog posts and resources.

Success! Now check your email to get the toolbox!

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

The post How to Make PBL a Reality in a Distance Learning Environment appeared first on John Spencer.