Making Time for Project-Based Learning

Education Rethink 2021-03-22

I’ve been at the college level for nearly six years and every time I visit one of my college students in the midst of their practicum, I am struck by how fast time moves in a classroom. It’s easy as a professor to forget the frantic pace, with the bells and the announcements and the interruptions that occur on a regular basis. I can sometimes forget what it’s like to have to scarf down a meal and run an errand in a twenty-two minute lunch period. Most teachers I know have crowded curriculum maps punctuated by fire drills, assemblies, field trips, and testing days. So, every time I visit a classroom, I’m struck by the breakneck pace of teaching. You’re always in a time crunch.

This is especially true this year during this period of pandemic pedagogy. Some teachers are still teaching virtually with huge challenges related to attendance and engagement. Others are in various hybrid models. So how do you make time for projects? How do we make time for project-based learning when your schedule is already packed? This is one of the most common questions I get when I lead PBL workshops and engage in coaching.

It can feel like you’re simply adding another item onto an already crowded plate. However, PBL isn’t about adding things to your plate. It’s about re-arranging your plate so that students can work at a deeper level. But how does this actually work? I’d like to explore how we can craft PBL units in a way that maximizes our time.

Listen to the Podcast

Listen to the Podcast

If you enjoy this blog but you’d like to listen to it on the go, just click on the audio below or subscribe via Apple Podcasts (ideal for iOS users) or Google Play and Stitcher (ideal for Android users).

https://spencerauthor.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Making-Time-for-PBL.mp3

Seven Strategies for Maximizing Time for Project-Based Learning

The following are specific strategies you can use to maximize time for PBL. Before getting into this, I want to share a quick caveat: it’s all about context. There are so many human dynamics at work and ultimately, you know your students the best. You are the expert. Often, we learn through trial and error. I had projects that tanked or went a full week off course. I still don’t have it figured out perfectly. However, I have learned a few strategies along the way, through my own experiences and through observing some amazing PBL teachers.

#1: Less Teacher Talk

This was the hardest one for me as a middle school teacher. Direct instruction can feel so efficient as a way to convey information. And it is. You talk, they listen and take notes, and that’s it. However, with PBL, students spend more time doing the work themselves. They ask more questions and find more of the answers on their own. Sometimes I am a guide, helping them out one-on-one. Other times, I am a curator, sharing specific resources they will need. But the goal is for me to talk less and for students to work more.

While this can feel less efficient, students often learn at a deeper level and retain the information for a longer period of time when they wrestle with it. It might not look as efficient but we actually save time by having students maximize their work time within a class period.

Note that isn’t just spending less time on direct instruction. It’s also the idea of spending less time explaining directions as students work on the project. I remember having an intern observing me and asking him to do a time audit of how I spent my class time in a PBL unit. To my surprise, I spent way too much time giving directions and clarifying directions for the whole class. So, I tried something. I would write the directions on the board and then answer clarifying questions as I walked around the room. It worked.

#2: Shorten the Timeline (But Build in Wiggle Room)

Ever noticed that students tend to waste time at the beginning or middle of a project and then rush toward the end to get it done? It turns out, we tend to work harder on a task when we are close to finishing it. By contrast, there’s an idea called Parkinson’s Law, that explains how “work expands to the time allotted” (as described by this great Planet Money episode). In other words, if you give yourself three weeks to do a project and it should only take two weeks, you will find a way to use all three weeks rather than finish early.

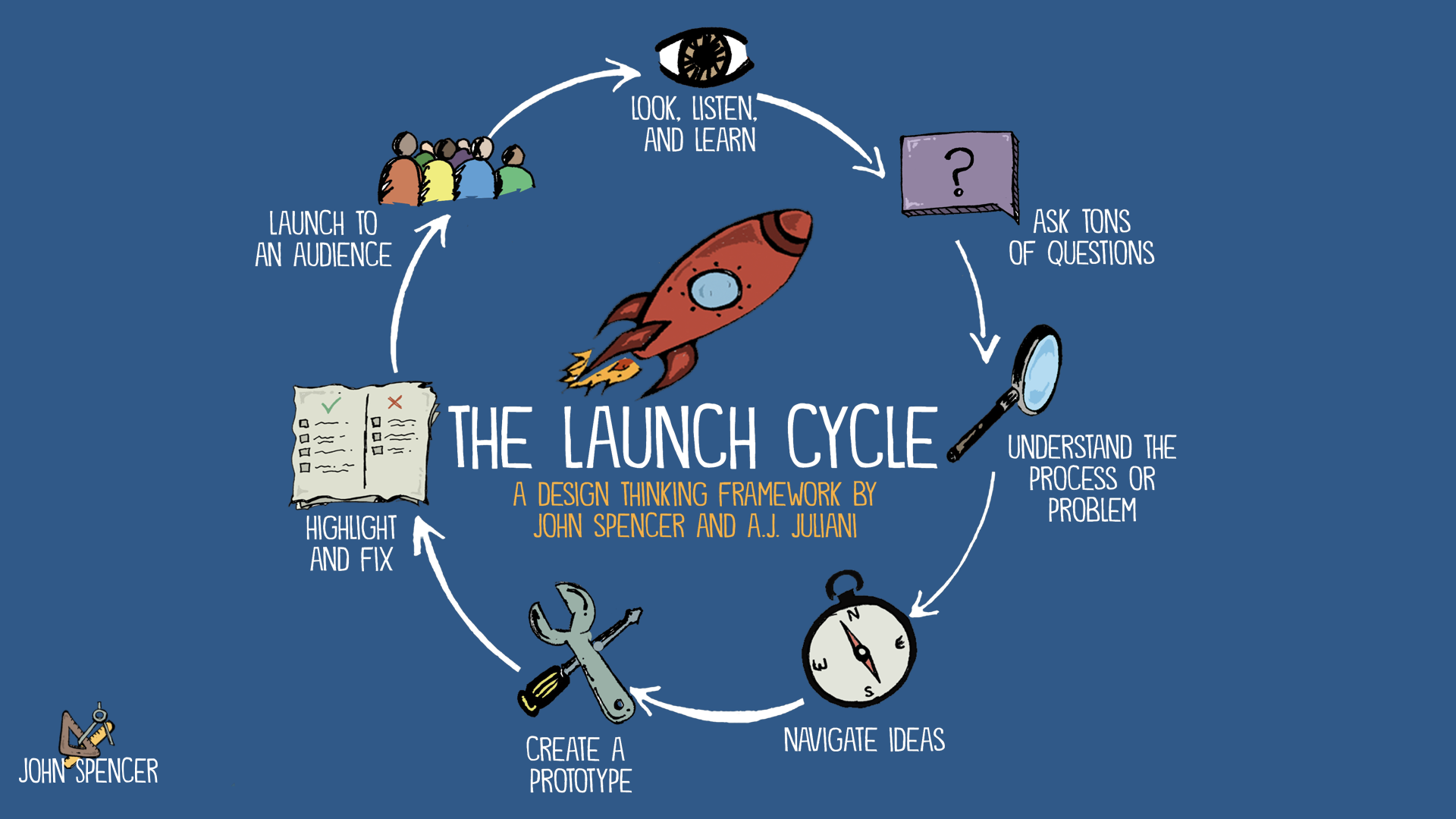

Now, there are definitely times when students rush through projects and finish early. However, often students will spend longer than normal on a project because the timelines are too loose. I’ve found that it’s easier to set tighter deadlines and then give students some additional days rather than creating really loose time deadlines. It helps to break projects into phases, which is why I love design thinking. With the LAUNCH Cycle, we have specific phases that students walk through as they engage in creative work:

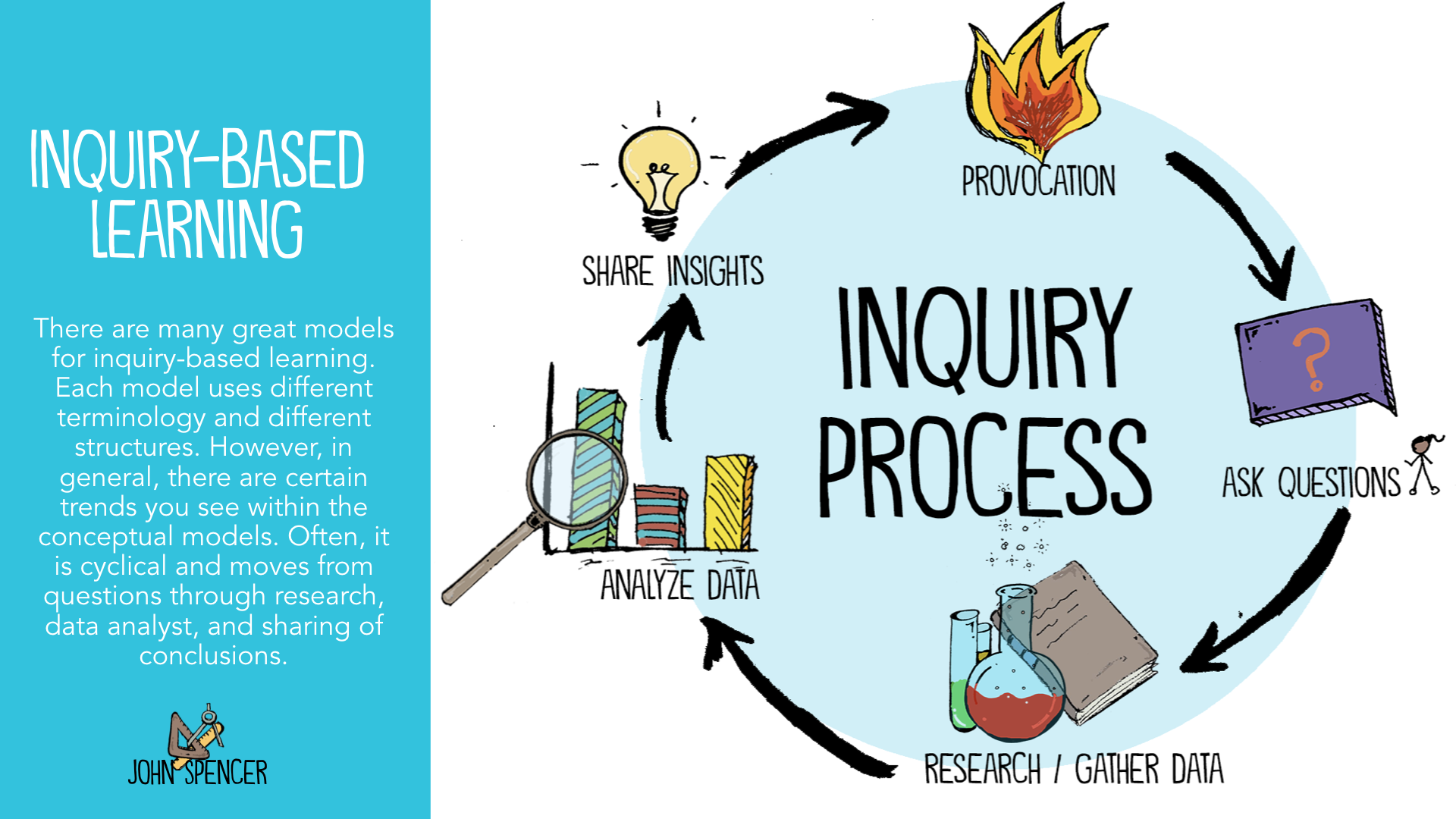

So, students move through inquiry, research, ideation, prototyping, and revision in distinct phases. Another option would be to structure it through the inquiry process:

So, students move through inquiry, research, ideation, prototyping, and revision in distinct phases. Another option would be to structure it through the inquiry process:

It also helps to have students keep track of their own progress by teaching them to engage in project management:

It also helps to have students keep track of their own progress by teaching them to engage in project management:

However, sometimes students struggle to meet deadlines, which leads to my next point.

#3: Focus on Quality Over Quantity

When I first began teaching, I would wait for the slowest student to finish an assignment before moving on as a class. So, when it took a student thirty-five minutes to write a paragraph, we would all wait thirty-five minutes. I then stuck with that same timeframe for the entire year. A few months into the school year, I had students fill out a survey on my teaching and, to my surprise, the biggest complaint was that we were moving too slowly. Finally, I realized that we could move faster and I could excuse students from a second assignment to finish the paragraph on their own.

Eventually, this led to a breakthrough for me. What if I got rid of the requirements around quantity and instead focused on quality. So, during a warm-up, I said, “Try and write at least a paragraph. Many of you will do two or three but the goal should be to get your thoughts across clearly.” When I switched to flexible assignments, students began to thrive. I no longer had students getting bored and off-task because they had finished early but I also didn’t have the students who were scared of being behind all the time.

As I moved to project-based learning, I realized that I needed to embrace flexible assignment design and allow students to focus on quality over quantity.

So, when we worked on blogging projects, I had students who wrote ten blog posts and others who wrote three. I had students who wrote 2,000-word posts and others who wrote three hundred words. Initially, there were questions of equity and fairness but because we framed it through the lens of personal goals, students realized that equity isn’t about sameness. It’s about helping each student reach their full potential. When we discussed it as a class, I would compare it to silent reading time, when each student read a different number of pages. Although it feels counterintuitive, this flexible approach actually saves time, because each student is more likely to work toward their maximum potential.

So, when we worked on blogging projects, I had students who wrote ten blog posts and others who wrote three. I had students who wrote 2,000-word posts and others who wrote three hundred words. Initially, there were questions of equity and fairness but because we framed it through the lens of personal goals, students realized that equity isn’t about sameness. It’s about helping each student reach their full potential. When we discussed it as a class, I would compare it to silent reading time, when each student read a different number of pages. Although it feels counterintuitive, this flexible approach actually saves time, because each student is more likely to work toward their maximum potential.

#4: Use Structures to Save Time

Early on in my PBL journey, I told students, “I want you to create a documentary. You need to develop a plan and then make it happen.” It didn’t happen. Students stood around talking without getting started. The larger project was too daunting, so I began to incorporate structures that would build interdependence and collaboration. For a deeper dive into this topic, check out my recent article and podcast episode on building structure and interdependence into group projects.

Structures are actually vital for creative productivity. It turns out people who are inexperienced at a task often fail to plan and have more false starts and mistakes while those who are experts tend to plan ahead. Structures provide the necessary creative constraint to push divergent thinking and they help facilitate the actual work of creative work. One of the fascinating things I’ve learned in researching collaboration and innovation is how often organizations, teams, and companies use structures to facilitate creative work.

Nearly every discipline uses a framework or blueprint for their creative work; whether it’s a writer’s workshop structure, an engineering process, the scientific method, or a design thinking framework. When we incorporate these frameworks into our PBL units, we not only save time, but we also teach students how to do creative work in various disciplines.

#5: Chunk Your Standards

The traditional approach to teaching focuses on isolating specific skills and teaching them systematically to students. However, with PBL, we can have students learn a concept while also practicing a skill. They can work on multiple, interconnected standards at the same time instead of going sequentially through each standard. When this happens, students move more slowly through the standards rather than going through the stop-and-go traditional methods.

In some cases, you might go fully competency-based and allow students to skip standards that they have already mastered. For example, in the research phase of a project, students can work on specific reading skills they need to master and skip the skills they have already mastered. For a mini-project, you might even have students use this choice grid, where they self-select skills and standards.

#6: Teach New Content Through the Project

According to PBL Works, one of the key differences between a culminating project and a PBL unit is that students should be learning through a project rather than learning first and then doing completing the project afterward.

Note that you will still need to do direct instruction and you might even begin your project with a quick concept attainment lesson. In fact, John Hattie recommends focusing on concept attainment before ever moving into student inquiry. Moreover, there are times when you might need to review a concept or a skill together with students before they move into a new phase of their projects. However, these more traditional approaches should occur throughout the project. The goal is to integrate direct instruction in a way that feels authentic.

#7: Assess As You Go

With project-based learning, you can incorporate frequent formative assessments into each phase of the project. Here you treat assessment more like a verb than a noun. It’s something you do rather than something you take. You can observe students as they work by keeping a checklist of mastery or pulling them aside for one-on-one conversations. You can also embed self-assessments, peer feedback, and shorter five-minute student-teacher conferences so that they can set goals and clarify their mastery of the content.

In the process, you save time, because you are not having students completing tests or weekly quizzes. This can feel risky. I remember wondering whether or not my observations were accurate and feeling afraid that my students would tank when it came time to take an actual test. For what it’s worth, I would always take thirty minutes to go over test-taking strategies at the end of each quarter when we took a benchmark test. However, because our projects were so challenging, students tended to excel on the tests. There was never a guarantee and the research on PBL and student achievement levels is mixed. However, when you teach above the test, students tend to view the test as easier.

Making Time for What Matters

Ultimately, project-based learning involves a different way of thinking. It’s about choosing quality over quantity and shifting toward student ownership. While it can feel like things are moving more slowly, you can actually accomplish more and learn at a deeper level.

If you’re interested in getting started with PBL, you might want to download this toolkit. You might also want to check out this free webinar I’m doing next week.

Get Your Free PBL Toolbox

Get this free toolbox along with, members-only access to my latest blog posts and resources.

Success! Now check your email to get the toolbox!

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

The post Making Time for Project-Based Learning appeared first on John Spencer.