Father Time: Chronos and Kronos

Waggish 2013-04-16

It is easy to confuse the Greek god of time, Chronos (Χρόνος), with Zeus’ Titan father, Kronos (Κρόνος). So easy, in fact, that the conflation has been made for over two thousand years. The Greeks conflated them regularly, at least according to Plutarch. The Romans then coopted Kronos into the form of Saturn, who later became known as Father Time and the god of time.

To make things even more confusing, sometime in the late Roman Empire, Saturn was then conflated with the Greek concept of kairos, which designates a pregnant or opportune “special” time. Kairos is somewhat opposed to chronos, which signifies day-to-day time in general. Chronos is the quotidian, the recurrent, the passing of the years, while kairos is the moment, the event, the suspension of the normal. But both were piled onto Saturn over the centuries.

Time is always a messy concept, in mythology and otherwise. I haven’t found a good overview of the nooks and crannies of these nominal twins; this is my attempt.

The Greek origins are frustratingly fuzzy, as usual. Chronos doesn’t appear in Hesiod’s Theogony, which tells the usual story of Kronos eating his children and then being tricked by his wife Rheia into regurgitating them, then being defeated by them (as well as Zeus, who Rheia hid).

But Chronos does appear in the cosmogony of the sixth century BCE writer Pherekydes of Syros. Pherekydes posits three primordial deities: Chronos, proto-Zeus figure Zas, and proto-Gaia figure Chthonie. Zas marries Chtonie and gives her the earth and sea as a wedding present, turning Chthonie into her present Ge, the earth. The gifts are partly created, however, by Chronos himself:

Zas always existed, and Chronos and Chthonie, as the three first principles.. .and Chronos made out of his own seed fire and wind [or breath] and water… from which, when they were disposed in five recesses, were composed numerous other offspring of gods, what is called ‘of the five recesses’, which is perhaps the same as saying ‘of five worlds’.

Fragment 52, Kirk, Raven, Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers

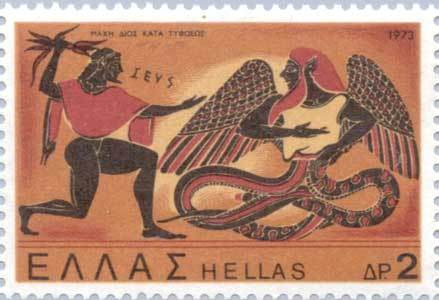

Then there is a big gap in our knowledge, and the next thing we have from Pherekydes is Kronos (not Chronos) fighting with Ophioneus over who should hold the heavens. Kronos wins. Apart from the oddness of Kronos allying with Zas, there are all sorts of other questions:

Scholars have generally assumed that at some point Chronos becomes Kronos, and Zas Zeus, and perhaps Ge Rheia. Such an assumption seems likely to be right, but poses some problems for our understanding of the relationship between Zeus and Kronos: do they clash as in Hesiod after the fall of Ophioeus, or are they allies in that battle and subsequently, with Zeus simply assuming a more prominent role toward the end of the poem? … There still remains the fact that Zeus (as Zas) and Kronos (as Chronos) have both existed forever, in contrast to Ophioneus, and there seems no good reason why either of them should suddenly engage in conflict with the other….

On the whole, then, I think it best to assume that Zas and Chronos work together in harmony from beginning (of which there is none) to end, and that the battle with Ophioneus (from his name clearly a Typhoeus counterpart) and his brood is the only conflict which Pherekydes envisioned.

Timothy Gantz, Early Greek Myth

Kirk and Raven say that Pherekydes was clearly “addicted to etymologies,” and so perhaps did the joining of similarly named gods, turning Time into a creator and Zeus and Kronos into allies.

Onto the post-classical Hellenistic world. In his book on the Orphic poems, M.L. West tells of Clement quoting from a hymn to a god that is both father and son to Zeus: “The god is probably Kronos (Chronos), called Zeus’ son because of the story in the Rhapsodic Theogony that Zeus swallowed the older gods and brought them forth again. Cf. Hymn 8.13″ This leaves us with the perplexing loop of Kronos killing both his father and children, only to have his surviving son become his father.

And the ourobourus is doubly appropriate because one of Chronos’ early forms was a winged serpent, which developed into a three-headed serpent in Orphic cosmogony:

The serpent form of Chronos may have its origins in Egyptian fantasy, but in Orphic poetry it took on a symbolic significance which justified its retention and elaboration. Chronos was represented, we are told, as a winged serpent with additional heads of a bull and a lion, and between them the face of a god. How is this to be imagined? The detail that the wings were `on his shoulders’ suggests that the whole upper part of his body was of human shape apart from the wings and extra heads. This is also indicated by the fact that his consort, who was `of the same nature’, had arms. If the couple are mainly anthropomorphic above the waist and snakelike below, they are reminiscent of Echidna (Hes. Th. 298-9, Hdt. 4.9.1), and even more of her consort Typhoeus as he is represented on a well-known Chalcidian hydria in Munich.

M.L. West, The Orphic Poems

West sees a common Indo-European origin to these myths shared by Indian, Egyptian, and Greek sources. He speculates:

The snake was an ancient and natural symbol of eternity because of its habit of sloughing its skin off and so renewing its youth. It may also be relevant that the serpent with human head and arms is the regular shape of river-gods. The idea of Time as a river is present in at least one passage of tragedy (Critias 43 F 3.1-3 `Tireless Time with his ever-flowing stream runs full, reborn from himself’); and it would be assisted by the fact that Oceanus is usually the father of rivers, if in the Orphic poem Chronos was represented as born to Oceanus. River-gods are not usually fitted with wings, of course, and would have no use for them. But they are a natural adjunct for a cosmic serpent with no earth to glide upon. We may compare the wings of Pherecydes’ world tree, and in art the wings of the sun’s horses. In a wider context, wings are freely bestowed by archaic artists upon all manner of divine beings, and fabulous monsters such as sphinxes and griffins are also winged; the type of the winged Typhoeus has its place with them. That Time should be winged is something in which it is easy to find symbolic meaning.

M.L. West, The Orphic Poems

As an anthropomorphic god, however, Chronos fades out while Kronos retains his standard position as Zeus’ father, parricide, and filicide in classical Greek sources.

Plutarch, though, continues to speak of a more figurative allegory known in the Orphic cults and to the Greeks in general:

And they are those that tell us that, as the Greeks are used to allegorize Kronos (or Saturn) into chronos (time), and Hera (or Juno) into aer (air) and also to resolve the generation of Vulcan into the change of air into fire, so also among the Egyptians, Osiris is the river Nile, who accompanies with Isis, which is the earth; and Typhon is the sea, into which the Nile falling is thereby destroyed and scattered, excepting only that part of it which the earth receives and drinks up, by means whereof she becomes prolific.

Plutarch, “Of Isis and Osiris”

Kronos was not the only one to be allegorized into chronos, however. There are bits of evidence of hero-demigod Herakles/Hercules also being equated with the winged serpent.

Athenagoras and Damascius both record that the winged serpent Chronos was also called Heracles. Why? What was there about Heracles that enabled him to be identified with a creature of such physical monstrosity and such cosmic importance? Only one plausible answer has so far been suggested. In the legendary cycle of twelve labours, in the course of which Heracles overcame a lion, a bull, and various other dangerous fauna, some allegorical interpreters saw the victorious march of the sun through the twelve signs of the zodiac. Time is measured by the sun and the solar year. It is thus that Heracles-Helios can be addressed by the author of the Orphic Hymns as `father of Time’ (12.3), and by Nonnus as `thou who revolvest the son of Time, the twelve-month year’ (D. 40.372). By the same token, it may be argued, the Orphic Chronos, Time himself, might be identified with Heracles, the indomitable animal-tamer of the zodiac.

However, there is another possibility. For Plato, time is defined by the complex movements of the sun, moon, and planets; and when they have played through all their permutations and returned to the same relative positions, the `perfect year’ and the `perfect number of time’ are complete. The early Stoics derived from this their doctrine of the Great Year, at the end of which the cosmos is totally dissolved into fire. They defined time as the dimension of cosmic movement. Time was therefore coextensive with the Great Year, and could be considered to pause in the ecpyrosis. Now we find in Seneca, after a thoroughly Stoic exposition of the identity of God, the author of the world, with Nature and Fate, the argument that he may be equated with (among other divinities) Hercules, `because his force is invincible, and when it is wearied by the promulgation of works, it will retire into fire’. The allusion is on the one hand to the Stoic ecpyrosis, on the other to the pyre on the summit of Mount Oeta in which Heracles was cremated and achieved apotheosis after completing his labours. In this Stoic allegorization of the Heracles myth, then, the cycle of labours corresponds to the totality of divine activity in the course of the Great Year. Since divine activity is coextensive with the cosmos, that means that Heracles’ labours represent everything that happens in cosmic time.

M.L. West, The Orphic Poems

This is admittedly rather speculative. It is noteworthy, however, because it links Chronos to one of two Greek cults that thrived heavily under Rome, those of Herakles and Dionysus.

The movement from the literal to the figurative is not the only direction. The process works in reverse as well. What subsequently happens is a combining and recombining in which incompatible features are freely merged and tossed away. Here the best single guide is Ernst Panofsky’s article “Father Time.”

In none of these ancient representations do we find the hourglass, the scythe or sickle, the crutches, or any signs of a particularly advanced age. In other words, the ancient images of Time are either characterized by symbols of fleeting speed and precarious balance, or by symbols of universal power and infinite fertility, but not by symbols of decay and destruction. How, then, did these most specific attributes of Father Time come to be introduced?

The answer lies in the fact that the Greek expression for time, Chronos, was very similar to the name of Kronos (the Roman Saturn), oldest and most formidable of the gods. A patron of agriculture, he generally carried a sickle. As the senior member of the Greek and Roman Pantheon he was professionally old, and later, when the great classical divinities came to be identified with the planets, Saturn was associated with the highest and slowest of these. When religious worship gradually disintegrated and was finally supplanted by philosophical speculation, the fortuitous similarity between the words Chronos and Kronos was adduced as proof of the actual identity of the two concepts which really had some features in common. According to Plutarch, who happens to be the earliest author to state this identity in writing, Kronos means Time in the same way as Hera means Air and Hephaistos, Fire.

The Neoplatonics accepted the identification on metaphysical rather than physical grounds. They interpreted Kronos, the father of gods and men, as nous, the Cosmic Mind (while his son Zeus or Jupiter was likened to its ‘emanation,’ the psyche, or Cosmic Soul) and could easily merge this concept with that of Chronos, the ‘father of all things,’ the ‘wise old builder,’ as he had been called. The learned writers of the fourth and fifth centuries A.D. began to provide Kronos-Saturn with new attributes like the snake or dragon biting its tail, which were meant to emphasize his temporal significance. Also, they re-interpreted the original features of his image as symbols of time, His sickle, traditionally explained eithcr as an agricultural implement or as the instrument of castration, came to be interpreted as a symbol of tempora quae sicut falx in se recurrunt; and the mythical tale that he had devoured his own children was said to signify that Time, who had already been termed ‘sharp-toothed’ by Simonides and edax rerum by Ovid, devours whatever he has created.

Ernst Panofsky, “Father Time”

Note that pace Panofsky, the snake/dragon imagery of time was not new to the 4th/5th centuries CE. Neoplatonics like Proclus were aware of the Orphic cosmogonies and were resuscitating an existing, though latent, symbolism.

Nonetheless, we have some ex post facto justification here. New explanations are created that invoke anachronistic features of the deities. If Kronos devouring his children originally had nothing to do with time, now it does. Time now becomes gloomy because Saturn is gloomy. In place of Orphic “unaging” Time, we now get aged, cranky, hungry Time.

Far from being an abstraction limited to philosophy, Time seems better thought of as one of those absolute metaphors darting between concept, symbol, and personification. Time latches onto Kronos because of a lexical similarity, but it latches onto Herakles through arcane associations mostly lost to us. It infects myths like a virus.

By the age of Petrarch (1304-1374), Renaissance humanism makes for a new recombination. Petrarch’s Triumphs portrays a menacing, conquering time. Saturn was readymade for the job. Saturn’s castrating scythe now signifies the ravages of time. (Destruction is always an easily-reappropriated metaphor.) The scythe also links time easily to his compatriot Death, who is associated with the scythe as early as the 11th century.

Small wonder that the illustrators decided to fuse the harmless personification of ‘Temps’ with the sinister image of Saturn. From the former they took over the wings, from the latter the grim, decrepit appearance, the crutches, and, finally, such strictly Saturnian features as the scythe and the devouring motif. That this new image personified Time was frequently emphasized by an hourglass, which seems to make its first appearance in this new cycle of illustrations, and sometimes by the zodiac, or the dragon biting its tail.

Ernst Panofsky, “Father Time”

And with this new conception of time, the menacing portions stick while the innocuous features–like the wings–do not, even though it was the wings that were associated with time in the first place! The serpent imagery is long-gone, overwritten by Christianity.

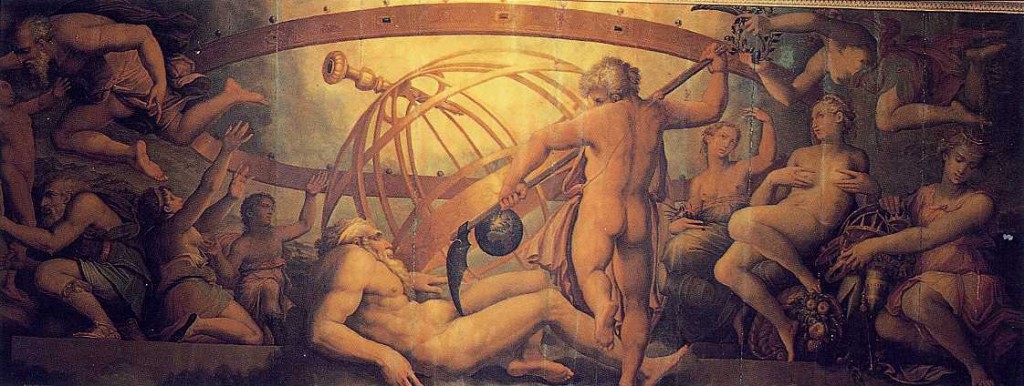

By this point, the idea of time devouring his children (not Zeus, but us) has taken on real metaphysical weight, and time the destroyer proceeds into the present day. It’s not Goya’s Saturn but Rubens’ Saturn that captures this new Saturn-as-Time, white beard, decrepit body, and staff/scythe.

Petrarch, Triumph of Time

Your grandeur passes, and your pageantry, Your lordships pass, your kingdoms pass; and Time Disposes wilfully of mortal things,

And treats all men, worthy or no, alike; And Time dissolves not only visible things, But eloquence, and what the mind hath wrought.

And fleeing thus, it turns the world around. Nor ever rests nor stays nor turns again Till it has made you nought but a little dust.

…

Time in his avarice steals so much away: Men call it Fame; ’tis but a second death, And both alike are strong beyond defense. Thus doth Time triumph over the world and Fame.

Related posts: