How To Help Your Students Develop A Growth Mindset

e-Literate 2020-05-27

How To Help Your Students Develop A Growth Mindset

contributed by Jackie Gerstein, usergeneratededucation

For professional development around growth mindset, contact TeachThought Professional Development to bring Jackie Gerstein and other TeachThought professionals to your school today.

I work part-time with elementary learners – with gifted learners during the school year and teaching maker education camps during the summer. The one thing almost all of them have in common is yelling out, “I can’t do this” when the tasks aren’t completed upon first attempts or get a little too difficult for them.

I partially blame this on the way most school curriculum is structured. Too much school curriculum is based on paper for quick and one-shot learning experiences (or the comparable online worksheets). Students are asked to do worksheets on paper, answer end-of-chapter questions on paper, write essays on paper, do math problems on paper, fill in the blanks on paper, and pick the correct answer out of a multiple-choice set of answers on paper. These tasks are then graded as to the percentage correct and then the teacher moves onto the next task.

So it is no wonder that when learners are given hands-on tasks such as those common to maker education, STEM, and STEAM, they sometimes struggle with their completion. Struggling is good. Struggling with authentic tasks mimics real life so much more than completing those types of tasks and assessments done at most schools.

Problems like yelling out, “I can’t do this” arise when the tasks get a little too difficult, but ultimately are manageable. I used to work with delinquent kids within Outward Bound-type programs. Most at-risk kids have some self-defeating behaviors including those that result in personal failure. The model for these types of programs is that helping participants push past their self-perceived limitations results in the beginnings of success rather than a failure orientation. This leads to a success-building through a success behavioral cycle.

How To Respond When Students Say ‘I Can’t Do This’

A similar approach can be used with learners when they take on an ‘I can’t do this’ attitude. Some of the strategies to offset ‘I can’t do this’ include:

Help learners focus on “I can’t do this . . . YET.”

Teach learners strategies for dealing with frustration.

Encourage learners to ask for help from their peers.

Give learners tasks a little above their ability levels.

Emphasize the processes of learning rather than its product.

Reframe mistakes and difficulties as opportunities for learning.

Scaffold learning; provide multiple opportunities to learn and build upon previous learning.

Focus on mastery of learning; mastery of skills.

Avoid the urge to rescue them.

May need to push learners beyond self-perceived limits.

Build reflection into the learning process.

Help learners accept an ‘it’s okay’ when a task really is too hard (only as a last resort).

Focus on “I can’t do this . . . YET.”

The use of “YET” was drawn from Carol Dweck’s work with growth mindsets.

‘Just the words “yet” or “not yet,” we’re finding give kids greater confidence, give them a path into the future that creates greater persistence. And we can actually change students’ mindsets. In one study, we taught them that every time they push out of their comfort zone to learn something new and difficult, the neurons in their brain can form new, stronger connections,and over time, they can get smarter.’ (Carol Dweck TED Talk: The power of believing that you can improve)

By asking learners to add ‘yet’ to the end of their ‘I can’t do this’ comments, possibilities are opened up for success in future attempts and iterations. It changes their fixed or failure mindsets to growth and possibility ones.

Teach learners strategies for dealing with frustration.

What often precedes learners yelling out, ‘I can’t do this’ is that learners’ frustration levels have gotten a bit too high for them. Helping learners deal with their frustrations is a core skill related to their social-emotional development and helps with being successful with the given tasks.

‘The basic approach to helping a [student] deal with frustrating feelings is (a) to help them build the capability to observe themselves while they’re in the midst of experiencing the feeling, (b) to help them form a story or narrative about their experience of the feeling and the situation, and then (c) to help them make conscious choices about their behavior and the ways they express their feelings.’ (Tips for Parents: Managing Frustration and Difficult Feelings in Gifted Children)

‘You can help your [student] recognize that learning involves trial and error. Mastering a new skill takes patience, perseverance, practice, and the confidence that success will come. Instead of recognizing that failure is temporary, a [student] often concludes, “I’ll never succeed.” That is why encouragement is by far the most important gift you can give your frustrated [student]. Take her dejection seriously, but help her look at her challenge differently: “Never,” you might reply, “is an awfully long time.” Eventually, she’ll learn from your encouraging words to talk herself out of giving up.’ (Fight Frustration)

Encourage learners to ask for help from their peers.

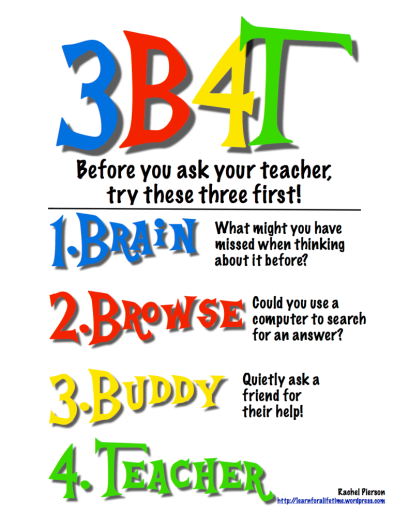

I must tell both my gifted students and my summer campers several times a day to ask one of their classmates for help when they are stuck. I have a three before me policy in my classrooms, but sometimes when I tell them to ask for help, they look at me like I am speaking another language. It makes sense, though, as they often have been socialized via school procedures to ask the teacher when they get stuck.

The following poster is going up in my classroom this coming year to remind them of the different possibilities for getting help if and when they get stuck on a learning task:

The bottom line becomes facilitating learner self-reliance knowing that these are skills learners can transfer to outside of school activities where there often is not a teacher to provide assistance.

Emphasize the processes of learning rather than its product.

School curriculum often focuses on the whats of learning – the products – rather than the hows of learning – the processes. When the focus changes to the process of learning, learners are less apt to feel the pressure to create quality products. “Research has demonstrated that engaging students in the learning process increase their attention and focus, motivates them to practice higher-level critical thinking skills and promotes meaningful learning experiences” (Engaging students in learning).

The biggest step an educator can take to implement a process-oriented learning environment is to let go of expectations about what a product should be. Expectations can and should be around learning processes such as: following through to the task completion, finding help when needed, trying new things, taking risks, creating and innovating, tolerating frustration, and attempting alternative routes when one route isn’t working.

Reframe mistakes & difficulties as opportunities for learning.

I’ve blogged about normalizing failure and mistake-making in The Over Promotion of Failure:

“I reframe the idea of failure, that oftentimes occur within open-ended, ill-defined projects, as things didn’t go as originally planned. It is just a part of the learning process. I explain to my learners that they will experience setbacks, mistakes, struggles. It is just a natural part of real-world learning. Struggles, setbacks, and mistakes are not discussed as a failure but as parts of a process that need improving.”

‘Contrary to what many of us might guess, making a mistake with high confidence and then being corrected is one of the most powerful ways to absorb something and retain it. Learning about what is wrong may hasten to understand of why the correct procedures are appropriate but errors may also be interpreted as failure. And Americans … strive to avoid situations where this might happen.’ (To Err Is Human: And A Powerful Prelude To Learning)

Scaffold learning; provide multiple opportunities to learn and build upon previous learning.

Many maker education, STEM, and STEAM activities require a skill set in order to complete them. For example, many of the learning activities I do with my students require the use of scissors, tape, putting together things. Even though some of the learners are as old as 6th grade, many lack these skills. As such, I do multiple activities that require their use. Learners are more likely to enjoy, engage in, and achieve success in these activities if related skills are scaffolded, repeated, and built upon.

‘In the process of scaffolding, the teacher helps the student master a task or concept that the student is initially unable to grasp independently. The teacher offers assistance with only those skills that are beyond the student’s capability. Of great importance is allowing the student to complete as much of the task as possible, unassisted. The teacher only attempts to help the student with tasks that are just beyond his current capability. Student errors are expected, but, with teacher feedback and prompting, the student is able to achieve the task or goal.’ (Scaffolding)

‘By allowing students to learn from their mistakes, or circling back through the curriculum will allow more students to access your instruction and for you to have a better understanding of where they are at with their learning. Let’s face it, learning can be messy and if you try to put it into a simple box or say a single class period and then move on, it isn’t always effective. (Strategies and Practices That Can Help All Students Overcome Barriers)’

Focus on mastery of learning; mastery of skills.

Sal Khan of Khan Academy fame has a philosophy that focuses on mastery of learning and skills that apply to all types of learning:

A problem, Khan says, is the next block of material builds on what the student was supposed to learn in the last lesson, and it’s usually more difficult to pick up. So a student learns only 75% of the material, we can’t expect that student to master the next section.

When students master concepts and learn at their own pace — all sorts of neat things happen. The students can actually master the concepts, but they’re also building their growth mindset, they’re building perseverance, they’re taking agency over their learning. And all sorts of beautiful things can start to happen in the actual classroom. (Sal Khan TED Talk Urges Mastery, Not Test Scores In Classroom)

This approach puts forward the notion that students should not be rushed through to more complex concepts without having the foundational knowledge needed to successfully transition to the next level.

Khan believes we should be teaching students to master the material before moving on, ensuring that students are given as much time and support as they need to tackle each new concept before trying to build upon it. As Khan says, you wouldn’t build the second floor of a house on a shaky foundation. Otherwise, it will collapse.

Mastery learning:

-Reframes a student’s sense of responsibility, where performance is viewed as the product of instruction and practice, rather than a lack of ability.

-Encourages a student to persevere and grasp knowledge they previously didn’t understand.

-Gives students the time and opportunity as they need to master each step, instead of teaching to fixed time constraints.

-Provides feedback and assessment throughout the learning process, not just after a major assessment.’ (Teaching for mastery)

Give learners tasks a little above their ability levels.

Giving learners tasks a little above their ability levels is actually a definition for differentiated instruction. It also helps to ensure that new learning will occur; that learners will be challenged to go beyond their self-perceived limitations. ‘People can’t grow if they are constantly doing what they have always done. Let them develop new skills by giving challenging tasks” (15 effective ways to motivate your team). As learners overcome challenges, they will be more likely to take on new, even more challenging tasks.

Avoid the urge to rescue them.

I’ve had learners cry (even as old as 6th grade), get angry, sit down in frustration.

Educators, by nature, are helpers. The tendency is for them to rescue learners from the stress and frustration of reaching seemingly unsurmountable challenges. But, and this is a big but, if educators do rescue them, then they are taking away learning opportunities, the possibility of the learner achieving success on his or her own.

May need to push learners beyond self-perceived limits.

This is the next step after not rescuing learners. The educator may have to push, encourage, cajole, coax, persuade, wheedle learners to go beyond what they thought possible. It is similar to a coach who really pushes her or his athletes. Sometimes it appears mean or callous.

The big caveat to being successful with this strategy is that the educator must first have a good relationship with the leaners; that learners really understand that the educator has their best interests at heart.

Build reflection into the learning process.

‘Time needs to be built into the day or class period where students reflect on what they’ve learned and make meaning of it. This helps with processing information as they reconcile it with their prior knowledge and work to make the information stick. This is a great opportunity for thinking to be clarified, questions to be sought, or learning to be extended.’ (Strategies and Practices That Can Help All Students Overcome Barriers)

Help learners accept an ‘it’s okay’ when a task really is too hard.

And only as a last resort, because it should be.

The post How To Help Your Students Develop A Growth Mindset appeared first on TeachThought.