IMF attacks the Stability and Growth Pact

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2014-06-26

The IMF recently called on the euro-zone leaders to In its 2014 Consultation – 2014 Article IV Consultation with the Euro Area Concluding Statement of the IMF Mission – (an annual event the IMF does with each contributing member) the IMF said that the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) in the euro-zone “has become excessively complicated with multiple objectives and targets. Compliance with fiscal targets has been poor, reflecting in part weak enforcement mechanisms. And there is a worry that the framework discourages public investment.” The IMF might have mentioned that it also discourages private investment. The failure to include that in their warning is a reflection of their continued belief that fiscal austerity is good for the private sector. The evidence is very clear – it is bad for every sector. But at least the IMF is joining the chorus in opposition to the manic rule-driven approach the euro bureaucrats have put in place. The IMF indicated that the euro-zone growth was still weak and that:

The recovery of private investment has been weaker than in most previous recessions and financial crises. In the first quarter of 2014, growth was weaker than expected and unevenly distributed across countries.

This is an important phase for the euro-zone because the medium- to long-term damage of the policy failures are starting to reveal themselves.

A recession goes through several stages and this one will be no different despite the fact that private balance sheets are a complicating factor in this episode (the so-called ‘balance sheet recession’). Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

The first phase is the build up of inventories as consumers start cutting their expenditure growth and business firms stop investing in new productive capital.

Businesses start to go bust and unemployment starts to rise sharply. There is a surge in short-term unemployment.

This reinforces the decision by households and firms to constrain spending and matters get worse.

Bankruptcies rise and banks stop lending. Old business cannot turnover debt and possible new entrants cannot get working capital to begin.

Asset prices fall and depending on the balance sheet status of firms and households, some or many will find themselves holding more debt than they have asset backing for.

The pool of short-term unemployed moves into the long-term pool (above 52 weeks) and skill loss accelerates, in addition to other pathologies associated with the social dislocation that unemployment brings.

Many of you will have seen a graph similar to the following. It shows real GDP for the Euro 18 countries (in millions of euros) from the first-quarter 1995 to the first-quarter 2014 (blue line). The solid red line is a simple linear extrapolation of the trend growth rate between the March-quarter 2000 and the March-quarter 2008 (which was the peak quarter before the crisis hit. We call this the potential real GDP path.

So you interpret the solid red as saying if real GDP for the euro-zone as a whole had grown uninterrupted on that trend in a linear fashion it would have followed that path.

The difference between the two solid lines is called the output gap because it tells us how far below the potential the economy is operating. Clearly the output gaps have been very large in the euro-zone since mid-2008. The picture clouds the reality that the output gap for the euro-zone as a whole is very unequally shared across the 18 member countries.

In a sensible policy environment, the governments would increase their fiscal deficits to the extent necessary to reverse the output gap. Remember, the graph is in real terms (nominal GDP deflated by a measure of inflation).

But it still represents a ‘real’ spending shortfall on what the economy could potential absorb without creating any inflationary problem.

The problem is that the longer the recession the more damage is caused and at some point, the productive potential of the economy shrinks. The dotted red line is indicative only. The process is neither linear or as switching as depicted.

Further, the output gaps will shrink even though the economy is still in a deep recession because of that shrinking potential. We always have to be on our guard when organisations such as the IMF and the OECD start talking about how the output gaps have declined, as if that is a good thing.

It is one of those concepts in macroeconomics where ambiguity reigns. It is not a simple measure because it can become smaller for good and bad reasons just as it can become larger for good and bad reasons.

A declining output gap that is associated with an acceleration in total spending, which, in turn, creates stronger employment growth is a good thing. The same narrowing associated with a decline in the productive potential of the economy as a result of declining investment is a bad thing.

This relates to the concept of hysteresis in economics, which means the present is a function of the path that the economy has taken to get here. Some people talk about path-dependence to describe this phenomenon.

My PhD was partly about this concept.

Hysteresis is a term drawn from physics and is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as :

… the phenomenon in which the value of a physical property lags behind changes in the effect causing it, as for instance when magnetic induction lags behind the magnetizing force.

My early work in the mid-1980s, which was a critique of the neo-liberal mainstream arguments about ‘natural rates of unemployment’ was based on the strong empirical observation that many perceived ‘structural imbalances’ are, in fact, of a cyclical nature. Accordingly, a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

The mainstream orthodoxy, at the time (and again now – in fact, whenever there is mass unemployment that they seek to deny), claimed that the persistently high unemployment was the result of supply-side shifts in the labour market – for example, changing attitudes of workers to search intensity (that is, workers were lazy and preferred to take subsidised leisure in the form of income support payments from government) – and that aggregate demand policies aiming to stimulate the economy would not reduce this unemployment.

Accordingly, micro economic reform was necessary in the form of attacks on welfare payments to the unemployed (for example, increased stringency of activity tests) if governments wished to reduce unemployment.

My conjecture was that any structural constraints that emerge during a large recession (for example, skill mismatched) can be wound back by strong fiscal policy stimulation. For example, recessions cause unemployment to rise and due to their prolonged nature the short-term joblessness becomes entrenched long-term unemployment. The unemployment rate behaves asymmetrically with respect to the business cycle which means that it jumps up quickly but takes a long time to fall again.

There is robust evidence pointing to the conclusion that a worker’s chance of finding a job diminishes with the length of their spell of unemployment. When there is a deficiency of aggregate demand, employers use a range of screening devices when they are hiring. These screening mechanisms effectively “shuffle” the unemployed queue. Among other things, firms increase hiring standards (for example, demand higher qualifications than are necessary) and may engage in petty prejudice.

To understand what happens during a recession we need to consider the cyclical labour market adjustments that occur.

The hysteresis effect describes the interaction between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates. The significance of hysteresis is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

In a recession, many firms disappear all together, particularly those who were using very dated capital equipment that was less productive and hence subject to higher unit costs than the best practice technology.

The skills associated with using that equipment become obsolete as it is scrapped. This phenomenon is referred to as skill atrophy. Skill atrophy relates not only to the specific skills needed to operate a piece of equipment or participate in a firm-specific process.

Long-term unemployment also erodes more general skills as the psychological damage of unemployment impacts on a worker’s confidence and bearing. A lot of information about the labour market is gleaned informally via social networks and there is strong evidence pointing to the fact that as the duration of unemployment becomes longer the breadth and quality of an unemployed worker’s social network falls.

Further, as training opportunities are typically provided with entry-level jobs it follows that the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall.

New entrants to the labour force – into the unemployment pool because of a lack of jobs – are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns).

As a result, both groups of workers – those made redundant and the new entrants – need to find jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

Therefore, workers enduring shorter spells of unemployment, other things equal, will tend to be more to the front of the queue. Firms form the view that those who are enduring long-term unemployed are likely to be less skilled than those who have just lost their jobs and with so many workers to choose from firms are reluctant to offer any training.

However, just as the downturn generate these skill losses, a growing economy will start to provide training opportunities as the unemployment queue diminishes. This is one of the reasons that economists believe it is important for the government to stimulate economic growth when a recession is looming to ensure that the skill transitions can occur more easily.

The long-run is thus never independent of the state of aggregate demand in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined.

By stimulating output growth now, governments also help relieve longer-term constraints on growth – investment is encouraged and workers become more mobile.

The problem compounds though, because the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken and the longer is a recession (that is, the output gap), the broader the negative hysteretic forces become. At some point, the productive capacity of the economy starts to fall towards the sluggish demand-side of the economy and the output gap closes at much lower levels of economic activity.

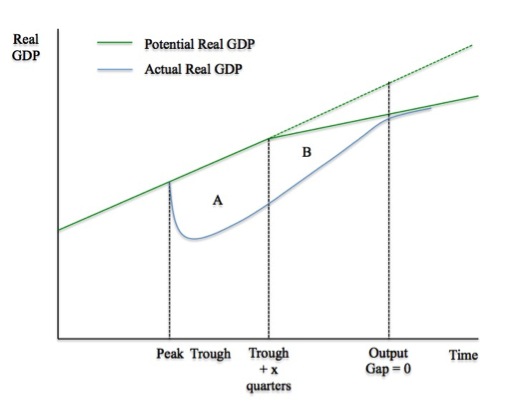

The following diagram shows how the demand-side and supply-sides interact following a recession to and find the long-run losses. Unlike the mainstream macroeconomics approach, which assumes that the “long-run” is supply-determined and invariant to the demand conditions in the economy at any point in time, the diagram shows that the supply-side of the economy responds to particular demand conditions.

There is a whole literature on the measurement of so-called sacrifice ratios, which attempt to measure the real GDP losses arising from deflationary monetary policy. Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point.

In terms of the following diagram, the potential output path is denoted by the green solid line noting the dotted green segment for later discussion. This is the level of real output it would be forthcoming if only available collective capacity (including Labour and equipment) was being fully utilised.

The potential real GDP assumes some constant growth in productive capacity driven by a smooth investment trajectory up until the point where it slow flattens.

If we assume that at the peak the economy was working at full capacity – that is, there was no output gap – then we can tell a story of what happens following an aggregate demand failure. The solid blue line is the actual path of real GDP.

You can see that the output gap opens up quickly as real GDP departs from the potential real GDP line. The area A measures the real output gap for the first x-quarters following the Trough. As the economy starts growing again as aggregate demand starts to recover (perhaps on the back of a fiscal stimulus, perhaps as consumption or net exports improve) after the Trough, the real output gap start to close.

However, the persistence of the output gap over this period starts to undermine investment plans as firms become pessimistic about the future state of aggregate demand. At some point, investment starts to decline and two things are observed: (a) the recovery in real output does not accelerate due to the constrained private demand; and (b) the supply-side of the economy (potential) starts to respond (that is, is influenced) by the path of aggregate demand takes over time.

As the recession endures, the capital stock of a nation either remains static or in extreme cases (such as Greece at present) it will contract.

The pessimism by firms begins to reduce the potential real output of the economy (denoted by the divergence between the solid green line and the dotted green line).

The area B denotes a declining output gap arising from both these demand-side and supply-side effects. At some point, actual real output reaches potential real output – meaning the output gap is closed – but the overall growth rate is much lower than would have been the case if the economy has continued on its previous real output potential trajectory.

The entrenched recession is thus not only caused major national income losses while the output gap was open but is also made that the growth in national income possible in this economy is much lower and the nation, in material terms, is poorer as a consequence.

Moreover, the inflation barrier (that is, the point at which nominal aggregate demand is greater than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it) occurs at lower actual real output levels.

The estimated costs of the recession and fiscal austerity are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit. The point of the diagram is that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken.

Those who advocate austerity and the massive short-term costs that accompany it fail to acknowledge these inter-temporal costs.

Declining investment ratios – a major casualty of the SGP

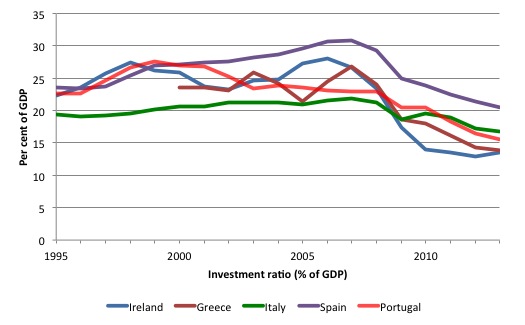

The following graph shows the investment ratio (% of GDP) for Ireland, Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal. The rabid application of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) not only undermined the capacity of most euro-zone nations to grow in the short-term but also undermined the investment environment that determined long-run growth potential.

Investment ratios across the euro-zone have fallen and in most cases continue to decline. The experience of the PIIGS is devastating. The collapse in their ratios has been sensational to say the least.

Investment flows (spending) add to total demand in the current period but also augment the capital stock.

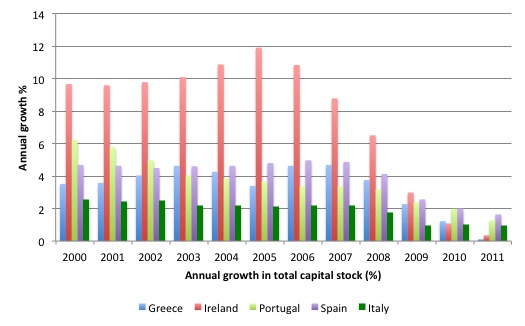

The data on capital stock is only available up until 2011. The following graph shows the annual growth in the gross capital stock for the PIIGS from 2000 to 2011. Note that there are two capital stock concepts: Gross and Net.

Gross capital stock reflects the market value of the stock of fixed productive assets in the economy and is an important determinant of the productive potential of the economy. The more capital per worker that can be employed the more productive, other things equal, the economy will be.

Net capital stock is the Gross stock less the depreciation and the loss through ageing, obsolescence etc. So if the gross capital stock is not growing in a year, then it is certain that the net stock will be shrinking.

Recessions accelerate the rate of capital scrapping.

You can see how rapidly the growth of the gross capital stock has fallen in the first two or three years of the crisis. The situation in 2014 will be much worse given that we have now had an additional three years about of recession and very pessimistic confidence levels.

The continued decline in the investment ratios in most euro-zone nations, including the large economies of France and Germany, make it certain that the capital stock in most nations will have flattened out or contracted.

Conclusion

What this tells us is that governments should do everything within their capacity to avoid recessions.

Not only does a strategy of early policy intervention avoid massive short-run income losses and the sharp rise in unemployment that accompany recession, but the longer term damage to the supply capacity of the economy and the deterioration in the quality of the labour force can also be avoided.

A national, currency-issuing government can always provide sufficient aggregate spending in a relatively short period of time to offset a collapse in non-government spending, which, if otherwise ignored, would lead to these damaging short-run and long-run consequences.

The “waiting for the market to work” approach is vastly inferior and not only ruins the lives of individuals who are forced to disproportionately endure the costs of the economic downturn, but, also undermines future prosperity for their children and later generations.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.