The myopia of neo-liberalism and the IMF is now evident to all

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2014-10-08

The IMF published its October – World Economic Outlook – yesterday (October 7, 2014) and the news isn’t good. And remember this is the IMF, which is prone to overestimating growth, especially in times of fiscal austerity. What we are now seeing in these publications is recognition that economies around the world have entered the next phase of the crisis, which undermines the capacity to grow as much as the actual current growth rate. The concept of ‘secular stagnation’ is now more frequently referred to in the context of the crisis. However, the neo-liberal bias towards the primacy of monetary policy over fiscal policy as the means to overcome massive spending shortages remains. Further, it is clear that nations are now reaping the longer-term damages of failing to restore high employment levels as the GFC ensued. The unwillingness to immediately redress the private spending collapse not only has caused massive income and job losses but is now working to ensure that the growth rates possible in the past are going to be more difficult to achieve in the future unless there is a major rethink of the way fiscal policy is used. The myopia of neo-liberalism is now being exposed for all its destructive qualities. The IMF say that:

In addition to the implications of weaker potential growth, the major advanced economies, especially the euro area and Japan, could face an extended period of low growth reflecting persistently weak private demand that could turn into stagnation. In such a situation, some affected economies would not be able to generate the demand needed to restore full employment through regular self-correcting forces. The equilibrium real interest rate on safe assets consistent with full employment might be too low to be achieved with the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates.

Be warned – this is more neo-liberal nonsense in the sense that it leaves out obvious solutions to any secular stagnation.

Here is the context. An economic cycle turns south when total spending falls below that expected by the producers of goods and services and they realise their production levels are too high relative to demand.

Inventory levels rise, sales orders fall and the spending weakness starts to multiply throughout the economy as laid-off workers adopt conservative positions with respect to the spending plans.

As the output gap (the difference between the what the economy can produce given its stock of capital equipment etc and the fully employed labour force and actual output) increases, unemployment rises and capacity utilisation rates fall.

A general malaise sets in with confidence among spenders (households who consume and firms who invest in new capital) falling. These positions are difficult to alter unless there is some external shock (for example, a government stimulus).

Income losses can be severe during this downturn and the malaise might extend for several periods (even years) if the governments do not use their fiscal capacity to fill the spending gap and provide a filip to private sector confidence.

Monetary policy (that is, the setting of interest rates or other measures such as quantitative easing) is unlikely to provide the demand boost and that incapacity has nothing really to do with the zero bound issue that the IMF mentions above.

A lot of nonsense has been written about so-called liquidity traps being the reason for the failure of monetary policy to stimulate aggregate spending.

Please read my blogs – The on-going crisis has nothing to do with a supposed liquidity trap and Whether there is a liquidity trap or not is irrelevant- for more discussion on this point.

Whether the interest rate is zero or something different there is no constraint on using fiscal policy to stimulate aggregate spending in a direct, targetted and immediate fashion.

The continual focus on monetary policy and the failure to mention fiscal policy options reflects the neo-liberal dominance and its ideological disdain for active fiscal policy intervention.

So the narratives try to eliminate any focus on the fiscal options by introducing claims that governments must maintain sustainable fiscal positions, which are usually defined in terms of deeply flawed concepts of fiscal space.

Please read my blog – Fiscal space is a real, not a financial concept – for more discussion on this point.

Most of the public angst during an economic downturn is thus focused on the immediate consequences of rising unemployment, lack of jobs, lost income and the distributional problems that emerge from these pathologies.

They can be severe and warrant immediate policy attention.

While not wanting to reduce the significance of the short-term costs of recession and the need for immediate policy interventions to restore high levels of employment, there are other reasons why policy intervention should be swift and scaled to mop up the output gap as soon as possible.

This is where the secular stagnation hypothesis enters the pictures. If governments do not set about using their fiscal capacities to restore growth as soon as they can then not only does the economy become stuck at below-full employment equilibrium states but the longer that state prevails the greater is the likelihood of long-run damage to the economy being caused.

The mainstream economics literature (text books, most of the New Keynesian models etc), which dominates the academy and the policy makers, considers the supply-side of the economy to be independent of the demand-side. The main models used in textbooks and policy advice continue to cast the supply-side of the economy as following a long-run trajectory which is independent of where the economy is at any point in time in terms of actual demand and activity.

What does that mean in English? Simply, that the path the economy takes is ultimately dependent on the growth in capital stock and population and the spending side of the economy will typically adjust through price flexibility. In other words, it doesn’t really matter if spending falls below the level required to fully engage the productive capacity of the economy at some point in time.

There will be temporary deviations from the potential growth path but soon enough, market adjustments (price and income shifts) will restore the level of spending (for example, prices fall and consumers spend more, which, in turn, stimulates more private investment spending etc). But the supply-side momemtum continues – and that defines the growth path of the economy.

A classic application of the separation of the supply and demand sides in mainstream economics is the claim that a wage cut will increase employment. They only consider wages to be a cost and so claim that if workers in a firm offer themselves at lower wages, unit costs will fall and firms can expand their sales by lowering prices accordingly.

That might happen at a firm-level because the drop in income from the wage cut is unlikely to have much effect on the sales levels of the firm in question. If true, then the supply side (the supply of labour and its cost) will be largely independent of the demand-side (total sales volume).

Even if true at that micro level, the problem is that at the macroeconomic level wages are not only a cost of production but they are also a major component of total income. If all wages are cut, national income will fall because workers will have less purchasing power and the sales of all firms will decline. As a result, the demand and supply sides of the economy are interdependent.

In the context of the secular stagnation this interdependence is a crucial factor. There is a concept in economics that I have written about before called hysteresis (which is a topic my own PhD was initially focused on).

Please read my blog – The intergenerational consequences of austerity will be massive – for more discussion on this point.

In brief, hysteresis is a term drawn from physics and is used in economics to describe where we are today as a reflection of where we have been. That is, the present is path-dependent.

An economy cannot escape its history. Mainstream economics largely ignores history or culture. The textbook models are ahistorical and assume that free market competitive principles apply universally across space and time.

There was an interesting article in today’s Sydney Morning Herald from economics writer Ross Gittins about the flaws in this starting point – see Moral trade-offs are for the common good

How is hysteresis relevant to the secular stagnation hypothesis?

The long-run position of the economy is never independent of the state of aggregate spending in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined.

By stimulating output growth now, governments not only reduce unemployment and income losses immediately but also help relieve longer-term constraints on growth – investment is encouraged and workers become more mobile.

The longer a recession (that is, the output gap) persists the broader the negative hysteretic forces become. At some point, the productive capacity of the economy starts to fall (supply-side) towards the sluggish demand-side of the economy and the output gap closes at much lower levels of economic activity.

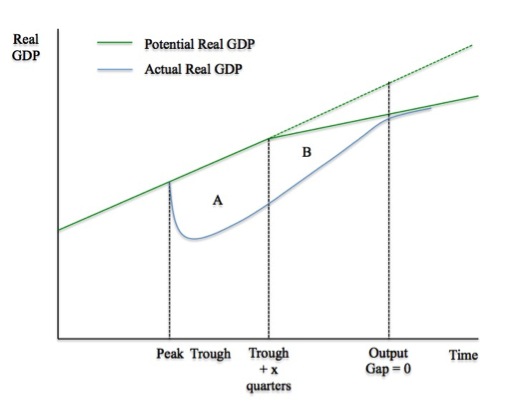

The following diagram shows how the demand-side and supply-sides interact following a recession. Unlike the mainstream macroeconomics approach, which assumes that the “long-run” is supply-determined and invariant to the demand conditions in the economy at any point in time, the diagram shows that the supply-side of the economy responds to particular demand conditions.

The potential output path is denoted by the green solid line noting the dotted green segment for later discussion. This is the level of real output it would be forthcoming if only available collective capacity (including Labour and equipment) was being fully utilised.

The potential real GDP assumes some constant growth in productive capacity driven by a smooth investment trajectory up until the point where it slow flattens.

If we assume that at the peak the economy was working at full capacity – that is, there was no output gap – then we can tell a story of what happens following an aggregate spending failure after the peak. The solid blue line is the actual path of real GDP or output that the economy takes.

You can see that the output gap opens up quickly as real GDP departs from the potential real GDP line. The area A measures the real output gap for the first x-quarters following the Trough. As the economy starts growing again as aggregate demand starts to recover (perhaps on the back of a fiscal stimulus, perhaps as consumption or net exports improve) after the Trough, the real output gap start to close.

However, the persistence of the output gap over this period starts to undermine investment plans as firms become pessimistic about the future state of aggregate spending.

At some point, investment starts to decline and two things are observed: (a) the recovery in real output does not accelerate due to the constrained private demand; and (b) the supply-side of the economy (potential) starts to respond (that is, is influenced) by the path of aggregate spending takes over time.

The pessimism by firms begins to reduce the potential real output of the economy (denoted by the divergence between the solid green line and the dotted green line).

The area B denotes a declining output gap arising from both these demand-side and supply-side effects. At some point, actual real output reaches potential real output – meaning the output gap is closed – but the overall growth rate is much lower than would have been the case if the economy has continued on its previous real output potential trajectory.

The entrenched recession is thus not only caused major national income losses while the output gap was open but is also made that the growth in national income possible in this economy is much lower and the nation, in material terms, is poorer as a consequence.

Moreover, the inflation barrier (that is, the point at which nominal aggregate demand is greater than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it) occurs at lower actual real output levels.

The estimated costs of the recession and fiscal austerity are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit. The point of the diagram is that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken.

Those who advocate austerity and the massive short-term costs that accompany it fail to acknowledge these inter-temporal costs.

Astute readers will note that this shrinking of the productive potential obviously has implications for the unemployment rate and what we might consider to be full employment.

This observation relates to the concept of “capacity-constrained” unemployment. This concept says that capacity constraints may create bottlenecks in production before unemployment has been significant reduced (this would be exacerbated if there are significant procyclical labour supply responses).

In this case any expansion in government spending may have insignificant real effects – that is, the real output gap is not large enough to allow all the unemployed to gain productive jobs.

However, it can be shown that while private sector investment, which is governed by profitability considerations can be insufficient (during and after a recession) to expand potential output fast enough to re-absorb the unemployed who lost their jobs in the downturn, such a situation does not apply to a currency-issuing government intent on introducing a Job Guarantee.

The point is that the introduction of a Job Guarantee job simultaneously creates the extra productive capacity required for program viability.

The spending capacity of currency-issuing governments is not constrained by expectations of future aggregate demand in the same way that pessimism erodes the spending decisions of private firms who are guided by profitability considerations.

From the research I have been involved with for many years, the majority of jobs identified as being suitable for low skill workers would be in the low capital intensity areas of work, although this would vary across the specific need areas (transport amenity; community welfare services; public health and safety; and recreation and culture etc).

The upshot is that the government has both the financial and real capacity to invest in and procure the required capital in a timely manner. Pessimism, which constrains private sector investment in productive capacity in the early days of recovery, doesn’t enter the picture.

Please read my blog – A Job Guarantee job creates the required extra productive capacity – for more discussion on this point.

The claim in the IMF World Economic Outlook, that “some affected economies would not be able to generate the demand needed to restore full employment through regular self-correcting forces” is true. Without fiscal intervention, the private market can get stuck in equilibrium states (where all decisions are being ratified by actual outcomes) which involve very high levels of unemployment.

So firms come to expect very low growth and reduce the rate of capacity creation while consumers adopt very cautious spending patterns. The resulting output and income generation reinforces these expectations and there is no dynamic to prompt a change. Firms have enough productive capacity and the economy gets stuck in this high unemployment state.

But the IMF’s claim that the “equilibrium real interest rate on safe assets consistent with full employment might be too low to be achieved with the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates” blatantly ignores the fiscal capacity of the currency-issuing governments to break into that cycle of low growth and high unemployment.

In that context, there is no comparison that can be made between the capacity of the Japanese government and those in the Eurozone to promote growth. Ignoring the ridiculous fiscal constraints imposed by the Stability and Growth Pact, the latter governments are financially constrained by the fact they use a foreign currency and the central bank (which issues that currency) is unwilling to underwrite fiscal deficits.

Japan is not constrained in that way at all. Its fiscal constraints are all voluntarily imposed and within the structure of the existing monetary system could be eliminated immediately. The Eurozone constraints are inherent in the structure of their monetary system and would require some changes to the Treaty – a torturous process. A Eurozone nation would be better advised to abandon the Euro and reinstate its own currency – something it could do in a very short time period if it had the political will.

But a currency-issuing nation could immediately create stronger economic growth with a Job Guarantee followed by other spending initiatives.

The IMF remains stuck in its neo-liberal Groupthink and claims for the Eurozone that:

… the pace of fiscal consolidation has slowed and the overall fiscal stance for 2014–15 is only slightly contractionary. This strikes a better balance between demand support and debt reduction.

But if the ECB guaranteed all debt issuance in the Eurozone, there would be no need for such austerity. European governments should in almost all cases have significantly larger deficits (double or larger in some cases) to address the medium- to longer-term effects of the crisis.

Justifying a position where fiscal policy “is only slightly contractionary” is continuing to justify the neo-liberal vandalism.

Conclusion

What all this means is that governments should do everything within their capacity to avoid recessions.

Not only does a strategy of early policy intervention avoid massive short-run income losses and the sharp rise in unemployment that accompany recession, but the longer term damage to the supply capacity of the economy and the deterioration in the quality of the labour force can also be avoided.

A national, currency-issuing government can always provide sufficient aggregate spending in a relatively short period of time to offset a collapse in non-government spending, which, if otherwise ignored, would lead to these damaging short-run and long-run consequences.

The “waiting for the market to work” approach is vastly inferior and not only ruins the lives of individuals who are forced to disproportionately endure the costs of the economic downturn, but, also undermines future prosperity for their children and later generations.

Ireland bullied by the Troika

Meanwhile, we learn from the article in the Irish Independent – Revealed – the Troika threats to bankrupt Ireland – that the Troika bullied Ireland into accepting a bailout plan.

In a new book of edited contributions just released, which considers the life and career of the former Irish Minister of Finance, Brian Lenihan, the Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland – Patrick Honohan – wrote that there was a teleconference in November 2010 between senior European and ECB officials and Irish government ministers, where:

The Troika staff told Brian in categorical terms that burning the bondholders would mean no programme and, accordingly, could not be countenanced,” Dr Honohan writes. “For whatever reason, they waited until after this showdown to inform me of this decision, which had apparently been taken at a very high-level teleconference to which no Irish representative was invited.”

Holohan was not invited nor knew about the teleconference meeting.

None of that is surprising.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.