The massive Eurozone real income losses continue to mount

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2015-12-22

Eurostat released the third quarter National Accounts data for Europe on Friday (November 13, 2015) – GDP up by 0.3% in the euro area and by 0.4% in the EU28 – which showed real GDP growth slowing in the Eurozone (down from the slug-like 0.4 per cent) and nations such as Finland and Estonia (one of the previous ‘poster children’ for austerity) heading into basket-case territory. Finland contracted by a sharp -0.6 per cent in the Third-quarter 2015 and has been in recession since the Estonia contracted by 0.5 per cent as did the beleaguered Greece. Portugal stagnated at zero growth. The so-called European recovery is looking distinctly wan! As at the third-quarter 2015, the Eurozone as a whole as still not reached real GDP levels equal to the peak in the March-quarter 2008. The overall 19 economy monetary union is still smaller than it was before the crisis began some 7.5 years ago. But to envisage how large the losses are of the failure of the policy makers to quickly restore growth, we have to also estimate where the Eurozone economy would have been had the GFC not occurred and pre-GFC growth rates were maintained. Then we have staggering losses of national income to consider across the failed monetary union. A very damaging folly has been inflicted on the people of Europe as a result of the neo-liberal Groupthink that dominates policy making.

A major reason for the overall slowdown was the decline in exports growth to the so-called emerging economies such as Brazil – with Germany and Italy bearing the brunt of that slowdown

You have to go to the respective national statistical agencies to get more detailed national accounts data so as to understand what was driving the poor result.

The Press Release (November 13, 2015) from the German Statistisches Bundesamt (DeStatis) – Gross domestic product up 0.3% in 3rd quarter of 2015 – tells us that in the third-quarter 2015:

… positive contributions were made mainly by domestic final consumption expenditure. The final consumption expenditure of both households and government was up again. By contrast, gross fixed capital formation decreased slightly. According to provisional calculations, the development of foreign trade also had a downward effect on growth because the increase in imports was markedly larger than that of exports.

The Italian Istat agency wrote on November 13, 2015 that real GDP rose by 0.2 per cent in the third-quarter 2015 down from 0.3 per cent in June and 0.4 per cent in March and that ()

Dal lato della domanda, vi è un contributo positivo della componente nazionale (al lordo delle scorte) e uno negativo della componente estera netta.

That is, unsold inventories had risen and there was a negative contribution from net exports.

The policy response – as far as any has been articulated by Eurozone leaders – is that the ECB will expand its quantitative easing program. On November 9, 2015, ECB boss Mario Draghi told the European Parliament in his – Introductory statement – that the central bank was not achieving its inflation target as “inflation dynamics … and … Signs of a sustained turnaround in core inflation have somewhat weakened.”

He said that the ECB would consider expanding the “asset purchase programme” which he thought was “a particularly powerful and flexible instrument” if they concluded the “medium-term price stability objective is at risk”, which is code for if the national accounts data continued to worsen.

In May 2014, American economist Laurence Ball produced a paper (NBER Working Paper No. 20185) – Long-Term Damage from the Great Recession in OECD Countries – which “estimates the long-term effects of the global recession of 2008-2009 on output in 23 countries”.

I will leave it to you to investigate his methodology if you are interested. It is fairly standard and should not be the issue.

Ball argued that:

… recession reduces an economy’s potential output. Potential output falls because a recession reduces capital accumulation, leaves scars on workers who lose their jobs, and disrupts the economic activities that produce technological progress.

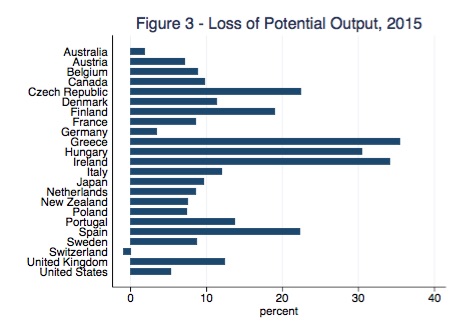

His Figure 3 (reproduced below) is interesting. It shows the “losses of potential output” as at 2015 as a result of the downturn in capital formation as a result of the GFC.

The calculations are slightly more optimistic than my own estimates but still in the ballpark.

This loss of potential output has two impacts: First, it means that domestic demand has been very weak or contracting in the years of the crisis. Second, it means that once growth is consolidated then the inflation ceiling is that much lower than it was previously and because growth will become capital constrained, the unemployment rates will remain high even though the economies might hit the ‘new’ peak.

One of my early academic articles (1985 with M.E. Burns) – Real Wages, Unemployment and Economic Policy in Australia (access PDF version HERE) – considered the arguments of the orthodox economists who urge governments to restrain their expenditure and to wait for a prophesied supply-side recovery and stimulate that recovery by cutting real wages.

The research was in the context of the recession in the early 1980s and built on work I had been doing in my PhD.

I discuss the article in more detail and articulate the concept of ‘capacity-constrained’ unemployment in this blog – A Job Guarantee job creates the required extra productive capacity.

Among other things, that paper demonstrated that actual and expected aggregate spending is the strongest influence on the level of activity and employment rather than real wage movements.

As a consequence, and running against the mainstream at the time, we made the case for public sector demand expansion rather than trying to engineer real wage cuts as a solution to the growing unemployment. We showed that “whatever the level of wages relative to the general price level, providing spare capacity exists a ceteris paribus increase in expected demand would lead to a similar percentage increase in output and permanent employment”.

Among other problems that might arise to hinder such an expansion we noted that:

… it may be that capacity constraints will create bottlenecks in production before unemployment has been significant reduced (this would be exacerbated if there are significant procyclical labour supply responses). In this case any expansion in government demand may have insignificant real effects and the crowding out argument has some validity.

Note, we were referring to ‘physical’ rather than financial crowding out here. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) clearly acknowledges that an economy could be pushed to the point that all real resources are in use and so if one sector (say the government) wants to increase its share of total resource use then it must come at the expense of another sector.

We argued that to avoid a chronic decline in capital formation, policy makers needed to intervene and stimulate growth and that would require “a significant government budget deficit”.

Ball used the term ‘hysteresis’ to describe the way potential output tracks the real output level down in a recession as capital formation slumps and workers’ skills atrophy.

The hysteresis literature provides a compelling testimony as to why there is a need for immediate policy interventions when the risk of recession increases. The government must move quickly to restore high levels of employment and mop up the output gap as soon as possible.

If governments do not set about using their fiscal capacities to restore growth as soon as they can then not only does the economy become stuck at below-full employment equilibrium states but the longer that state prevails the greater is the likelihood of long-run damage to the economy being caused.

One of the main focii of my Phd thesis was the presence of hysteresis, which I traced to labour market changes that occurred during a downturn – as skill losses rose.

Hysteresis means ‘path dependence’ – or where the economy is at today is a product of where it has been previously.

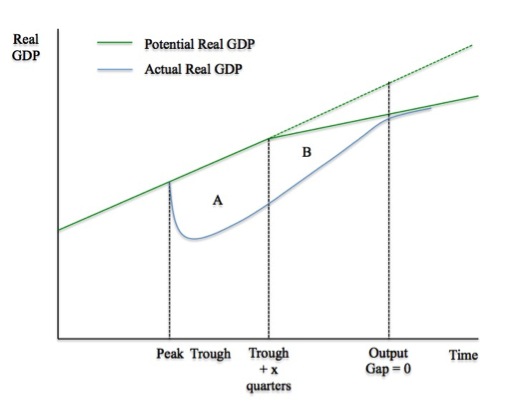

I produced the following diagram in this blog – The myopia of neo-liberalism and the IMF is now evident to all

It shows how the demand-side (actual real GDP) and supply-sides (potential real GDP) interact following a recession. Unlike the mainstream macroeconomics approach, which assumes that the ‘long-run’ is supply-determined and invariant to the demand conditions in the economy at any point in time, the diagram shows that the supply-side of the economy responds to particular demand conditions.

The potential output path is denoted by the green solid line noting the dotted green segment for later discussion. This is the level of real output it would be forthcoming if available collective capacity (including labour and equipment) was being fully utilised. The potential real GDP assumes some constant growth in productive capacity driven by a smooth investment trajectory up until the point where it flattens.

If we assume that at the peak the economy was working at full capacity – that is, there was no output gap – then we can tell a story of what happens following an aggregate spending failure after the peak. The solid blue line is the actual path of real GDP or output that the economy takes.

You can see that the output gap opens up quickly as real GDP departs from the potential real GDP line. The area A measures the real output gap for the period from the Peak to the Trough plus x-quarters (that is, including the early stages of the recovery).

As the economy starts growing again as aggregate spending recovers (perhaps on the back of a fiscal stimulus, perhaps as consumption or net exports improve) the real output gap start to close.

However, the persistence of the output gap over this period starts to undermine investment plans as firms become pessimistic about the future state of aggregate spending.

At some point, two things are observed: (a) the recovery in real output does not accelerate due to the constrained private demand; and (b) the supply-side of the economy (potential) starts to shrink as a result of the path that aggregate spending takes over time.

The pessimism by firms begins to reduce the potential real output of the economy (denoted by the divergence between the solid green line and the dotted green line).

The area B denotes a declining output gap arising from both these demand-side and supply-side effects. At some point, actual real output reaches potential real output – meaning the output gap is closed – but the overall growth rate is much lower than would have been the case if the economy has continued on its previous real output potential trajectory.

The entrenched recession is thus not only caused major national income losses while the output gap was open but is also made that the growth in national income possible in this economy is much lower and the nation, in material terms, is poorer as a consequence.

Moreover, the inflation barrier (that is, the point at which nominal aggregate demand is greater than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it) occurs at lower actual real output levels.

The estimated costs of the recession and fiscal austerity are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit. The point of the diagram is that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken.

Those who advocate austerity and the massive short-term costs that accompany it fail to acknowledge these on-going and permanent losses.

It is clear that growth builds on itself. But when private spending is stagnant and expectations are very pessimistic what external force will change that? Why will investors once again assume the risk and start building new capacity?

In more recent work (about a decade ago), Joan Muysken and I developed a framework for understanding investment cycles. Here is a working paper you can get for free (subsequently published in the literature) that summarises the work.

We considered the idea that investors who face endemic uncertainty about the future state of aggregate spending in the economy and who make large irreversible capital outlays, become cautious in times of pessimism and introduce broader safety margins in their risk analysis.

Accordingly, firms form expectations of future profitability by considering the current capacity utilisation rate against their normal usage. They will only invest when capacity utilisation, exceeds its normal level. Thus, investment varies with capacity utilisation within bounds and therefore productive capacity grows at rate which is bounded from below and above. The asymmetric investment behaviour thus generates asymmetries in capacity growth because productive capacity only grows when there is a shortage of capacity.

This sort of model stands up very well to empirical scrutiny.

Please read my blogs – How do labour markets react to capacity utilisation changes? and Deficits should be cut in a recession. Not! – for more discussion on this point.

Astute readers will note that this shrinking of the productive potential obviously has implications for the unemployment rate and what we might consider to be full employment.

This observation relates to the concept of ‘capacity-constrained’ unemployment. This concept says that capacity constraints may create bottlenecks in production before unemployment has been significant reduced (this would be exacerbated if there are significant procyclical labour supply responses).

In this case any expansion in government spending may have insignificant real effects – that is, the real output gap is not large enough to allow all the unemployed to gain productive jobs.

In the blog – A Job Guarantee job creates the required extra productive capacity – I argued that while private sector investment, which is governed by profitability considerations, can be insufficient (during and after a recession) to expand potential output fast enough to re-absorb the unemployed who lost their jobs in the downturn, such a situation does not apply to a currency-issuing government intent on introducing a Job Guarantee.

The point is that the introduction of a Job Guarantee job simultaneously creates the extra productive capacity required for program viability.

The spending capacity of currency-issuing governments is not constrained by expectations of future aggregate demand in the same way that pessimism erodes the spending decisions of private firms who are guided by profitability considerations.

From the research I have been involved with for many years, the majority of jobs identified as being suitable for low skill workers would be in the low capital intensity areas of work, although this would vary across the specific need areas (transport amenity; community welfare services; public health and safety; and recreation and culture etc).

The upshot is that the government has both the financial and real capacity to invest in and procure the required capital in a timely manner. Pessimism, which constrains private sector investment in productive capacity in the early days of recovery, doesn’t enter the picture.

All this bears on a recent article by Financial Times economist Martin Wolf (November 10, 2015) – In the long shadow of the Great Recession.

Martin Wolf wrote that:

The US and Europe still live with the legacies of the financial crisis of 2007-09 and the subsequent eurozone crisis. Could better policies have prevented that outcome; and, if so, what might they have been?

This question, of course, bears on the continued obsession with monetary policy in the Eurozone as a saviour for the stagnation.

Martin Wolf asks two questions:

1. “could the adverse impact of the crisis have been smaller?”

2. “can it still be reversed?”

He proceeds to answer YES to both.

On the first, he says that:

… it would have required stronger fiscal and monetary responses, and more aggressive restructuring of damaged financial institutions. The eurozone, in particular, should have done far better. Yet, even today, it lacks the will and the institutions it needs.

By resorting to austerity to force nations to stay within the fiscal rules set out in the Stability and Growth Pact, which were, in fact, hardened, during the crisis, the European Council, ensured that the crisis would be long-lasting and extremely damaging.

I have never seen any cost-benefit analysis (either publicly released official analyses or in documents that are leaked) which show the European Commission had estimated the damage that their strategy was likely to cause and how long the impacts on potential output would last.

The austerity was inflicted as if the fiscal rules had some scientific authority and were appropriately calibrated and that the recovery would be rapid and negate any ‘hysteresis’ effects.

This was just the ideology of the neo-liberal Groupthink talking. It was a sort of ‘close your eyes and hit’ strategy that bottom order batsmen (and women) use in cricket. They always get out and usually fail to make any scores (runs).

The fiscal rules were an ad hoc contrivance – I explain how the 3 per cent rule emerged in my my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015).

Worse still, they have proven to be totally inadequate in relation to the sort of fiscal swings that the automatic stabilisers generated much less any changes in discretionary fiscal policies.

The cyclical response alone (the automatic stabilisers with no policy change) as tax revenues collapsed drove the fiscal balances in most Member States above the ‘allowable’ SGP limits. It was madness to tighten fiscal policy to meet the rules while private spending was so weak.

The policy response guaranteed that a long and deep recession would ensue. And it has. And now without adequate fiscal support, Eurozone growth predicated on the export-led mania of the neo-liberals, is once again slowing as China rebalances its own economy and moves down to lower, more sustainable growth rates.

In terms of his second question, Martin Wolf believes that the losses can be reversed. He wrote:

The answer to whether the losses in output levels and growth rates can be reversed must again be yes.

However, his use of the term ‘reverse’ is problematic.

He should have made the point clearer that the losses of prolonged recession as in the Eurozone are permanent and cannot be reversed. The lost income that arises because of recession is gone forever. Each day that real GDP and national income is below the potential level is a day that the lost income disappears forever.

As noted above, the task of policy interventions, early in a downturn, is to minimise those losses.

Martin Wolf illustrates his argument by saying that:

By the early 1960s GDP per head in the US had regained the level indicated by a continuation of pre-1929 trends.

As an aside, I think he must be meaning early 1940s rather than early 1960s. The growth rate in real GDP per head in the US prior to 1929 and after the recession in the early 1920s was about 3.1 per cent.

Extrapolating that trend shows that by 1940 to 1942 (depending on how the trend is extrapolated), real GDP per capita in the US was back to its 1929 level. It then accelerated sharply after World War II (after a slight downturn as the US turned its policy structures to peace).

From the previous quote then, we learn that Martin Wolf considers a “reversal” to be achieved if real GDP per capita passes some pre-recession level.

Satisfying that condition does not restore all the daily real GDP and national income losses that occurred prior to the point where real GDP gets back on the previous growth path. It just means that a previous growth path can be reached again after a prolonged recession.

Martin Wolf notes the US at the time was helped by the “fiscal boost from the second world war … [that] … cannot be repeated in peacetime”.

Well, in fact, the stimulus can be repeated in peacetime and would mean that instead of building weapons and machines to blast the hell out of each other, we build infrastructure that enhances public well-being – better-equipped schools, improved public transport systems, better and more inclusive health care systems, and environmentally-sustainable land and water works, among any number of other productive uses of public spending.

Martin Wolf recognises this and writes “A mix of aggressive support for demand and contributions to long-term supply — notably via far higher levels of public investment — would hit both objectives at once”.

So you have to wonder what the Eurozone leaders think is reality. The ECB policy machinations will not achieve these sort of outcomes. There is no chance in the world of that happening.

Juncker’s grand investment plan is delayed in the bureaucracy and is pitiful in scope anyway.

Meanwhile, growth stumbles overall, while some nations head into deep recession (Finland, Estonia etc).

Conclusion

Just as the Russian Sport’s Minister has promised a root-and-branch clean out of athletics administrators, coaches, doctors and other support staff (we will believe that when we see it) to purge the nation’s sport of endemic corruption and incompetence (as evidenced by them being thrown out of world athletics), the European Commission needs a major purge.

The European Parliament needs to take over the running of things and introduce policies that reflect the will of the people. The European Commission should be largely disbanded and made an administrative support for the Parliament.

Otherwise, even Martin Wolf’s sense of recession reversal is going to take longer and longer. As of the third-quarter 2015, the Eurozone as a whole (19 nations) has not yet caught up to the real GDP level that prevailed at the last peak (March-quarter 2008).

As at the third-quarter 2015, Greece was 26.3 percentage points below the March-quarter 2008 peak and Italy was 9 percentage points below. As at the second-quarter 2015 (latest data), Spain was 5.3 percentage points below the 2008 peak, Finland was 6.6 percentage points below the 2008 peak, and Portugal was 6.5 percentage points below the 2008 peak. A host of other European nations are in similar parlous shape.

And that is only comparing the current level of real GDP with the March 2008 level. It says nothing of where the potential real GDP path would have taken these nations had the recession been avoided.

The losses are thus massive – almost beyond belief.

Politics in the Pub – Hamilton – November 17, 2015

Tomorrow evening (Tuesday, November 17, 2015) I will be the speaker at the Politics in the Pub, which is held at the Hamilton Station Hotel, Beaumont Street, Hamilton (a suburb of Newcastle, NSW).

The title of my talk will be ‘Why budget deficits are good for Australia’ and I will motivate the talk with the quote from US philospher Daniel Dennett who told the New York Times on April 29, 2013 that:

There’s simply no polite way to tell people they’ve dedicated their lives to an illusion …

We will have some fun with that!

The event starts at 18:30.

I hope to see local readers there.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.