Finland should exit the euro

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2015-12-23

I think the progressive side of politics has a real problem when it is increasingly gazumped in policy insights by politicians and/or commentators from the populist, xenophobic, racist, homophobic, far right-wing. Whether Finland’s Foreign Minister Timo Soini is all of those things or just nationalistic and far right (one of the members of his Finns party wants homosexuals and some foreigners rounded up and sent to some remote Baltic Sea island), he is certainly correct when he told the press yesterday that “Finland should never have signed up to the single currency union” and “could have resorted to devaluations had it not been for its Euro membership” (Source). Earlier this month (December 4, 2015), Statistics Finland published the latest National Accounts data for the third-quarter 2015, which showed that real GDP declined by 0.5 per cent in that quarter and by 0.2 per cent over the previous 12 months. In the past 12 months, both exports and imports declined by 3.4 per cent, the former signalling declining markets and the latter declining domestic income – both bad. Investment spending fell by 3.9 per cent in the year to September, which will further undermine the nation’s potential growth. It is now becoming the basket case of advanced Europe.

After that rather sobering introduction to the basket case of advanced Europe, consider the following third-quarter real GDP results (Source):

In real terms, non-seasonally adjusted Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the first three quarters of 2015 increased by 4.5% compared with the same period of 2014. Total domestic final expenditure increased by 6.2%. Private final consumption increased by 4.4%, government final consumption by 0.9% and gross fixed capital formation by 15.8%. While the balance of trade in goods and services improved in nominal terms, the contribution to growth of foreign trade was negative as exports grew by 7.4% and imports grew by 10.9%.

That doesn’t sound as though it is describing a basket case economy.

What country do you think this data belongs to (and don’t check the Source link before you have a guess)?

I will come back to discussing this data soon.

Since my visit to Finland in October of this year I have been increasingly studying various reports and thinking about what an exit from the euro would mean for the nation. My conclusion is that it would be unambiguously better for Finland to immediately exit the Eurozone, restore its own currency and floated on international markets.

Over the next several months, I will write more about that thinking.

For reference and background, my most recent blogs on Finland are:

1. Finland – more austerity is not the answer

2. The Unit Labour Costs obsession in Finland

3. Full video – University of Helsinki lecture, October 9, 2015

I don’t intend traversing again the issues relating to the demise of Nokia and the loss of export capacity in its forest products sector as a result of structural shift in the media (newspaper) industry.

I mentioned recently that the Finnish parliament will soon debate whether the nation should exit the euro and restore its own currency.

A petition has gathered at least 50,000 votes, which means the parliament is required to formally debate the issue.

So will follow that parliamentary debate (when it happens) with some interest, although the latest euro barometer poll suggests that around 60 per cent of Finns still wish to remain in the common currency. However, that proportion has fallen from around 70 per cent in the last 12 months and continues to point south.

As the economic situation declines further on the back of the austerity intent of the current coalition government, one would expect the degree of dissatisfaction with the nation’s membership of the EMU to increase further.

There are also conservative forces (for example, the EuroThinkTank), which are providing analysis to show that Finland would be better off if it abandoned the common currency and floated its own currency, like Sweden.

For example, earlier this month (December 7, 2015), an economist from the EuroThinkTank, argued – Why Finland would be better off without the euro.

Given the conservative background of this economist, it is no surprise that his argument is based upon the rigidity of elevated labour costs in the face of declining industrial prosperity and the inability of Finland to alter its exchange rate to restore international competitiveness.

But, one thing that the article does get right is that when Finland last encountered a major economic downturn – the Great Depression between 1990 and 1994 – which was driven by the massive over expansion of a deregulated banking system (which it shared with Sweden) and the impacts of the collapse of the Soviet Union (given Finland’s particular exposure to the old Soviet system) – it adjusted through a large exchange rate depreciation.

I don’t intend to add to the voluminous literature on the 1990s collapse in this blog. But while real GDP growth in Finland fell by 10.4 per cent between March 1990 and December 1993 (the trough), something else of significance happened.

The following graph shows the evolution of the Finnish Markka, the currency in use before they abandon their currency sovereignty to enter the Eurozone, from January 1971 to December 2001.The parity is expressed in terms of the amount of Markka per US dollar.

So a rise in the graph indicates a depreciation and vice versa.

The first thing to note is the large swings in the currency, which allowed Finland to adjust to its external situation without having to cut domestic wages.

Once the Great Depression ensued after a sustained period of exchange rate appreciation driven by a massive investment boom, the currency depreciated by some 40 per cent between July 1991 and March 1993.

The following graph shows the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) measure of real effective exchange rates for Finland, Germany and Iceland between January 2005 and November 2015.

You can learn about this data from their publication – The new BIS effective exchange rate indices – which appeared in the BIS Quarterly Review, March 2006.

There was an earlier publication – Measuring international price and cost competitiveness – which appeared in the BIS Economic Papers, No 39, November 1993.

Real effective exchange rates provide a measure on international competitiveness and are based on information pertaining movements in relative prices and costs, expressed in a common currency. Economists started computing effective exchange rates after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s because that ended the “simple bilateral dollar rate” (Source).

The BIS ‘real effective exchange rate indices’ (REER) adjust nominal exchange rates with other data on domestic inflation and production costs.

The BIS say that:

An effective exchange rate (EER) provides a better indicator of the macroeconomic effects of exchange rates than any single bilateral rate. A nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is an index of some weighted average of bilateral exchange rates. A real effective exchange rate (REER) is the NEER adjusted by some measure of relative prices or costs; changes in the REER thus take into account both nominal exchange rate developments and the inflation differential vis-à-vis trading partners. In both policy and market analysis, EERs serve various purposes: as a measure of international competitiveness …

If the REER rises (falls) then we conclude that the nation is less (more) internationally competitive.

It is clear that Finland and Germany are moving in lock step and so gains from measures that might be taken internally are lost.

Please read my blog – Eurozone unemployment – little to do with international competitiveness – for more discussion on this point.

But Iceland is the interesting case. It had a huge collapse in 2008-09. But its government did not engage in widespread internal devaluation. Instead, the exchange rate fell sharply which gave the nation instance gains in international competitiveness.

Once the crisis subsided, you can see that the exchange rate increase has seen the REER for Iceland rise again somewhat.

The point is that gains to international competitiveness (if that matters) are much better achieved by allowing the exchange rate to move in response to external imbalances that the markets want to redress than attacking the local wages and conditions.

First, depreciation impacts on all import prices. The nation as a whole has to take a real income loss and then the question is how is that shared.

Notwithstanding the fact that exports then become more attractive to foreigners, the depreciation also gives domestic residents and firms an incentive to substitute away from those goods where possible.

So when the Australian dollar, for example, is weaker, we travel less overseas and take holidays within Australia. This boosts domestic demand and sustains employment.

Firms have an incentive to alter production or engage in new product innovations. I have noted before that Greece, for example, exports its world class olives to Germany and Italy for processing into olive oil. If their exchange rate depreciated somewhat, then it would provide incentives to local processors to start up and investment would be attractive in that sector.

There are many examples such as that.

Second, depreciation does not alter nominal incomes within the domestic economy, whereas internal devaluation does. This is quite a significant difference.

Most liabilities are specified in nominal terms (for example, mortgages). If real income levels are being reduced, people who hold nominal liabilities have to reduce expenditure on some items to ensure their nominal incomes can meet their liabilities.

Depreciation of the currency in international markets provides scope for domestic residents to make those sorts of shifts in spending.

But internal devaluation directly reduces nominal incomes and makes it much harder to rearrange household spending patterns to ensure all nominal liabilities can be serviced.

It is therefore a much more damaging path to improving competitiveness.

Finally, it is clear that increasing productivity will also reduce ULCs. The Finnish government is facing an on-going recession which needs more spending to redress.

Private spending (particularly capital formation) is weak. Internal devaluation will suppress domestic consumption growth even further.

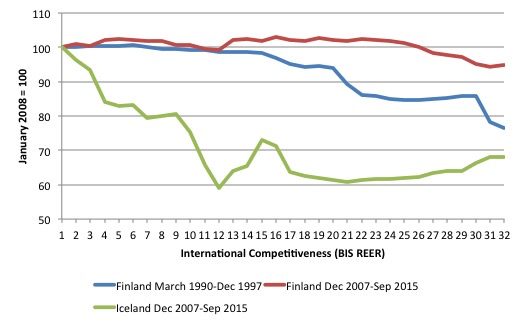

Now consider the following graph, which shows the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) measure of real effective exchange rates for Finland between March 1990 in February 1998 (blue line), Finland between December 2007 and November 2015 (red line), and Iceland between December 2007 and November 2015 (green line).

The numbers on the horizontal axes refer to the months after the peak in real GDP corresponding to each period.

The results are rather stunning. The graph should also be understood in terms of the initial graph I presented showing the post 1970 history of the Finnish markka (see above).

Before Finland entered the Eurozone its exchange rate was clearly able to adjust to provide stimulus to the economy as noted above. The adjustment for Finland in the early 1990s was not as rapid as it was for Iceland in 2008, but the ultimate depreciation (the sustained change) was clearly similar.

Conversely, within the Euro, Finland has had no room to move in this regard, which means that a key adjustment process for a sovereign currency is deliberately excluded.

The article cited above notes that:

The period of the floating markka was described by monetary calm and very fast economic growth. During this period, Finland also made a qualitative leap from resource-based economy to knowledge-based one with the ICT as the leading sector.

That point is obvious and demonstrates this sort of structural shifts that occur when exchange rates are flexible rather than fixed.

In that sense, I agree with the article’s conclusion that:

All historical facts point to the same conclusion: Finland should never have joined the euro. If Finland would have its own (floating) currency, it would depreciate against other currencies when there would be fall in global demand, the exchange rate of her main export partners would depreciate or when there would be an increase in the domestic production costs (e.g., wages). When Finland joined the euro, it gave up this instrument …

In the history, monetary unions have always broken down (either partially or completely) without a functional federal structure.

Even if I have serious misgivings about some of the analysis presented in that article, the statements above are clearly correct.

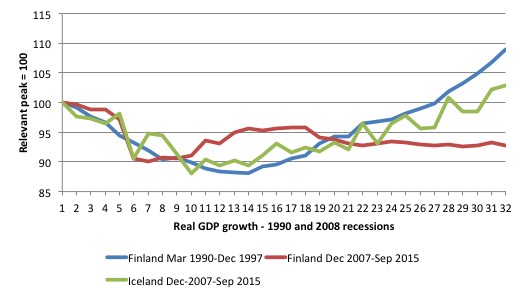

To see why this matters, consider the following graph, which shows indexed real GDP growth (100 = peak) for Finland between the March-quarter 1990 and the December-quarter 1997 (that is, the Great Depression period), and for Finland and Iceland between the December-quarter 2007 and the September-quarter 2015.

The horizontal axis indicates quarters after the peak real GDP was reached.

The results are fairly obvious. Each episode was severe in its magnitude. The adjustments in the aftermath of the crises were drawn out.

You can see how took for real GDP in Finland to cross the 100 line again – December-quarter 1996 – 28 quarters. Iceland took the same number of quarters (28) before its real GDP index once again crossed the hundred mark.

However, in the current crisis, real GDP in Finland is continuing to diverge from its December 2007 peak and is now 7.3 per cent below that Mark and continuing to decline.

Two significant things were different in 1990 in Finland and in 2008 in Iceland relative to 2008-2015 in Finland.

1. Finland has been constrained by the unworkable fiscal austerity imposed by the European Commission in the current episode. While Iceland didn’t embark on a fiscal splurge it did alternate fiscal policy in such a way that household disposable income was increased.

2. The exchange rate can no longer adjust for Finland.

I also remind readers that the official unemployment rate in Finland is currently 3.5 per cent) as at November 2015, where is the unemployment rate in Finland is 8.2 per cent with a sharply declining participation rate holding that rate down somewhat.

Conclusion

I will write more about these matters in further blogs. But it is a shame that it has to be left to the Finns party and some mainstream conservative economists to articulate the case for euro exit in Finland.

The progressive politicians are stuck in there world of glorious Europe and can’t see the reality that that political dream is crumbling around them and major two-party systems are falling apart (checkout the Spanish election results as an example).

The data quiz at the outset – obviously the real GDP data was the latest release for Iceland.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.