The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2016-05-06

Financial Times journalist Wolfgang Münchau’s article (April 24, 2016) – The revenge of globalisation’s losers – rehearses a common theme, and one which those on the Left have become intoxicated with (not implicating the journalist among them). The problem is that the basic tenet is incorrect and by failing to separate the process of globalisation (integrated multinational supply chains and global capital flows) from what we might call economic neo-liberalism, the Left leave themselves exposed and too ready to accept notions that the capacity of the state has become compromised and economic policy is constrained by global capital. This is a further part in my current series that will form the thrust of my next book (coming out later this year). I have broken sequence a bit with today’s blog given I have been tracing the lead up to the British decision to call in the IMF in 1976. More instalments in that sequence will come next week as I do some more thinking and research – I am trawling through hundreds of documents at present (which is fun but time consuming). But today picks up on Wolfgang Münchau’s article from the weekend and fits nicely into the overall theme of the series. It also keeps me from talking about deflation in Australia (yes, announced today by the Australian Bureau of Statistics) as the Federal government keeps raving on about cutting its fiscal deficit (statement next Tuesday). I will write about those dreaded topics in due course.

Wolfgang Münchau’s basic tenet is that:

Globalisation and membership of the eurozone in particular have damaged not only certain groups in society but entire nations

Globalisation is failing in advanced western countries, where a process once hailed for delivering universal benefit now faces a political backlash. Why? The establishment view, in Europe at least, is that states have neglected to forge the economic reforms necessary to make us more competitive globally.

I would like to offer an alternative view. The failure of globalisation in the west is in fact down to democracies failure to cope with the economic shocks that inevitably result from globalisation — such as the stagnation of real average incomes for two decades. Another shock has been the global financial crisis — a consequence of globalisation — and its permanent impact on long-term economic growth.

His thesis and the mainstream counter-thesis that dominates economic policy making at present resonate broadly through the political debate.

He argues that it is the “the combination of globalisation and technical advance” that “destroyed the old working class and is now challenging the skilled jobs of the lower middle class”.

As a result, the voting public are in revolt and are now challenging their governments who offer more ‘structural reforms’ (read: attacks on the conditions and security of employment).

He refers to the recent protests in France where the French government is trying to push through harsh labour market policy changes, which will worsen the plight of the labour force and has he notes “could result in the loss of their jobs, with no hope of a new one”.

True enough.

He also cites the 2003 Hartz policies (I don’t think it is sensible to call them reforms) in Germany which “succeeded in the short term because they raised the country’s cost competitiveness through lower wages relative to other advanced countries. The reforms produced a state of near full employment only because no other country did the same. If others had followed, there would have been no net gain.”

True enough.

Please read my blog – Germany is not a model for Europe – it fails abroad and at home – for more discussion on the so-called German ‘Jobwunder’.

A reasonable argument can be made that Gerhard Schröder helped cause the Eurozone crisis. His government’s response to the restrictions that Germany encountered on entering the EMU are certainly part of the story and one of the least focused upon aspects.

Upon entering the EMU, Schröder was under immense political pressure to do something about the high unemployment in the East after reunification.

Without the capacity to manipulate the exchange rate, the Germans understood that they had to reduce domestic production costs and inflation rates relative to other nations, in order to retain competitiveness.

The Germans thus took the so-called ‘internal devaluation’ route that is all the rage in Europe now, well before the crisis; a move, which ultimately has made the crisis worse.

When Schröder unveiled his Government’s ‘Agenda 2010’ in 2003, it was clear that they were going to cut into the income support systems and ensure that Germany’s export competitiveness endured despite abandoning its exchange rate flexibility.

The Hartz ‘reforms’ led to a major shift in national income shares away from workers towards profits, which has been a characteristic of the neo-liberal era.

The capitalist dilemma was that real wages typically had to grow in line with productivity to ensure that the goods produced were sold. If workers were producing more per hour over time, they had to be paid more per hour in real terms to ensure their purchasing power growth was sufficient to consume the extra production being pushed out into the markets.

How does economic growth sustain itself when labour productivity growth outstrips the growth in the real wage, especially as governments were trying to reduce their deficits and thus their contribution to total spending in their economies? How does the economy recycle the rising profit share to overcome the declining capacity of workers to consume?

While most nearly the rest of the world solved this problem by deregulating financial markets and heralding the rise of the ‘financial engineer’ whose job it was to push ever-increasing debt onto households and firms to ensure spending growth kept pace with the growth in productive capacity, as real wages growth remained suppressed, Germany adopted a particular version of this ‘solution’.

For Germany, the large export surpluses provided the funds to loan out to other nations.

Germany didn’t experience the same credit explosion as other nations. The suppression of real wages growth in Germany and the growth in the (very) low-wage ‘mini-jobs’ meant that Germany severely stifled domestic spending up to 2005

Schröder’s austerity policies forced harsh domestic restraint onto German workers, which meant that Germany could only grow through widening external surpluses.

So the external strategy, which has caused irreparable harm to its Eurozone partners, has also impoverished its own population. The German approach, which is echoed in the basic design of the common currency and the fiscal and monetary rules that reinforce it, could never be a viable model for prosperity throughout Europe.

Wolfgang Münchau concurs:

The reforms had a big downside. They reduced relative prices in Germany and pushed up net exports in turn generating massive savings outflows, the deep cause of the imbalances that led to the eurozone crisis. Reforms such as these can hardly be the recipe for how advanced nations should address the problem of globalisation.

He also points to discontent in Britain (Brexit issues), the US (about to nominate Trump as GOP candidate), Finland (“a non-recovering basket case — and it has a strong populist party”) as examples of growing discontent with the mainstream political processes that have delivered these ‘reforms’.

Take careful note of the way I phrased that last sentence. I will come back to it.

His explanation for the political discontent is as follows:

My diagnosis is that globalisation has overwhelmed western societies politically and technically. There is no way we can, or should, hide from it.

And his solution:

… we have to manage the change. This means accepting that the optimal moment for the next trade agreement, or market liberalisation, may not be right now.

He questions why the “leader of Germany’s Social Democrats and economics minister, is such an ardent advocate of TTIP” and notes that a “large number of supporters of the anti-immigrant Alternative für Deutschland party are former SPD voters.”

He advocates saying “no to TTIP”.

And indicates that the costs of not saying ‘no’ in the past has brought the world “close to the point where globalisation and membership of the eurozone in particular have damaged not only certain groups in society but entire nations. If the policymakers do not react to this, the voters surely will.”

And I agree with all of that.

So what is the disagreement?

Quite simply that globalisation is not the problem. The problem is neo-liberalism. Note that Wolfgang Münchau’s discussion is mostly about policy reform and the reaction of people to the consequence of those reforms.

That should tell you something.

He doesn’t talk about the way in which global supply chains have emerged and become highly sophisticated. He doesn’t talk about the diversity of products now available at relatively low prices (if you have an income).

His discussion centres on poorly conceived economic policy changes and the aftermath of them. About compliant electorates who went along with these neo-liberal politicians and who are now finally waking up to the nightmare.

In other words, what he is really railing against is not globalisation but neo-liberalism, which are quite separate developments.

Globalisation is a multi-faceted development that spatially reorganises economic activity (if allowed) and has, to some extent been part of social developments for as long as we have records.

Göran Therborn wrote (2000: 153) that:

Like so many concepts in social science and historiography, ‘globalization’ is a word of lay language and everyday usage with variable shades of meaning and many connotations.

He tries to tie down a definition to give the concept meaning and concludes that globalization refers:

… to tendencies to a world-wide reach, impact, or connectedness of social phenomenon or to a world-encompassing awareness among social actors.

So in that context, you and I are participating in a globalised social process – me writing to an international audience and connecting ideas with people all around the globe.

Another question that has to be considered is whether globalisation is “a system or a stage” (Therborn, 2000: 155). It is clear from a systems perspective that the world economy is not “fully systemized” (p.155). The example Therborn uses is the on-going process of development the European Single Market.

The Europeans are still a long way from completing that project and the global events are continually being “shaped by sub-global forces, be they cultural areas, nations, states or sub-state regions, and so on” (p.155).

What appears to have developed is an international arena for economic activity that is shaped by these sub-global forces. This is why Wolfgang Münchau talks about so-called ‘reform’ processes at the nation level.

These processes shape the way the activity within the international economic arena occurs and the impacts it delivers.

Interestingly, in the – Communist Manifesto (1848) – Marx and Engels discuss the way that discoveries of new lands (America, Rounding the Cape, etc) “opened up fresh ground for the rising bourgeoisie”. They wrote:

The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. To the great chagrin of Reactionists, it has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilised nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. And as in material, so also in intellectual production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature.

So the search for new markets and new ways of organising production is not new and has been going on for centuries.

The important point is that the way that these global developments manifest is, in now small part, influenced by the political developments that accompany them in time.

Therborn delineates six stages of globalisation starting back with the spread of religious ideas in the C4th AD.

He considers that we are now in the 6th stage “in which the politico-military dynamic of the Cold War has been overtaken by a mainly financial-cum-cultural one. This took off in the second half of the 1980s with the enormous expansion of foreign currency trading after the breakdown … of the international Bretton Woods currency system, followed by the trading of derivatives and other new instruments of high-level gambling” (p.163).

[Reference: Therborn, G. (2000) ‘Globalizations: Dimensions, Historical Waves, Regional Effects, Normative Governance’, International Sociology, 15(2), pp. 151-179

Certainly in the early 1970s, governments became financially unconstrained and floated their exchange rates, which freed their central banks from engaging in official foreign exchange market intervention.

But at the same time a major ideological shift occurred, which I have documented extensively in this series of blogs on the way the Left has been duped into believing that ‘globalisation’ has evaporated the power of the state.

As the organisation of production was shifting globally, the scourge of right-wing ‘free market’ thinking began to win the battle of ideas. I have documented that emergence in quite some detail.

Whatever we want to call the emergence – and I use the term neo-liberal now although in the late 1960s it might have been called Monetarism – the genus that started out with a focus on the money supply as a narrative to oppose discretionary fiscal and monetary interventions by the state – has broaded out over the ensuing period to become a full-scale attack on the capacity of the state to influence economic outcomes, apart from those that benefit the top-end-of-town.

So we first saw the debates about capital controls and the demands by Wall Street to abandon them so that new markets could emerge. Industrial capital demanded the abolition of tariffs unless they were to their advantage.

And then we saw the wave of privatisations to shift wealth and income-generating capacity to the private elites. That was accompanied by the destruction of national state monopolies in the big essential industries and user-pays principles for other state-provision.

And as this process of neo-liberalism has unfolded, more and more demands are made by international capital with the TPPs-type arrangements being the latest wave.

The idea that state intervention into market activity should be reduced to a bare minimum is now the dominant mantra. But that has nothing to do with globalisation per se. It interacts with globalisation but is separate and separable.

To reinforce the ‘free market’ ideology (which is nothing to do with free markets anyway as outlined in the mainstream textbooks that are used as authorities to justify the demands), the elites knew they had to penetrate the state decision-making processes.

As David Harvey (2006: 145) notes:

… the advocates for the neoliberal way now occupy positions of considerable influence in education (the universities and many ‘think tanks’), in the media, in corporate boardrooms and financial institutions, in key state institutions (treasury departments, the central banks) and also in those international institutions such as the IMF and the WTO that regulate global finance and trade. Neo-liberalism has, in short, become hegemonic as a mode of discourse, and has pervasive effects on ways of thought and political-economic practices to the point where it has become incorporated into the common-sense way we interpret, live in and understand the world.

[Reference: Harvey, D. (2005) ‘Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction’, Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 88(2) 145-158.]

So, the neo-liberals knew what the capacity of the state was – well and truly – and have tried to take over the state!

Meanwhile, during the period that nations were becoming free of the restrictions imposed on them by the Bretton Woods system, the Left became besotted with notions that the deep crisis that accompanies the massive OPEC oil price hikes was to be found in the lack of taxing capacity of governments.

They failed to understand that with fiat currencies, sovereign governments were no longer revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. They didn’t have to issue debt any longer and the role of taxation was not to raise revenue but to give the government ‘fiscal space’ in which to spend.

The situation became worse when the ‘Left’ – at both the political and intellectual levels – started incorporating the increasing global nature of finance and production-supply chains into their analysis. They wrongly assumed that these trends further undermined the capacity of states to spend and maintain full employment.

The ‘fiscal crisis of the state’ and ‘globalisation’ were held out as the two major impediments to state sovereignty. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

But this mythology progressive became the perceived ‘wisdom’ of the Left in the 1970s and the neo-liberal resurgence as Monetarism, then privatisation and austerity, became virtually unchallenged as the ‘Left’ became lost in various post-modern debates that amounted to nothing important at all.

As one journalist wrote recently (January 5, 2016) (Source):

The international Left promotes its own image rather than engaging in the bitter reality of resistance against neoliberalism. It does not need to believe in postmodernism because it is postmodernism.

The thesis that follows is that the “Left hasn’t failed to resist neoliberalism. Perhaps it has not even tried.”

Academic journals publishing so-called ‘progressive’ material became overwhelmed with all sorts of post modern deconstructions of this and that, while the main game, the macroeconomics debate was lost – in a no contest.

Despite being eulogised by the Left, the only contribution that key left-wing academics such as James O’Connor made in the 1970s were negative – teaching the Left that the government was financially constrained and could not run continuous deficits because it would run out of money.

As with no resistance at all in the offing, “Neoliberalization has in effect swept across the world like a vast tidal wave of institutional reform and discursive adjustment, and while there is plenty of evidence of its uneven geographical development, no place can claim total immunity (Harvey, 2006: 145).

There is no question that if we hadn’t been so complacent and ready to be bought off by mass consumerism, the neoliberalisation could have been stopped even as the processes of globalisation continued.

There is no doubt that the big international companies prefer a free run across national borders as they do their utmost to coopt governments in their favour.

Conclusion

But last time I looked, the likes of Coca-Cola and Apple did not have assembled armies.

Last time I looked, companies like Microsoft were brought to heel by judicial processes applying national laws.

Last time I looked, companies like BHP Billiton had to pay huge fines after being found guilty of corruption within a national border (Source).

We could list countless examples.

The point that Wolfgang Münchau makes about people becoming polarised because the promises of their politicians are not coming to fruition is valid.

But the problem is not the global trends in supply chains etc. Rather it is that their elected representatives have become co-opted by neo-liberal elites who fully understand that state power can be skewed to work in their favour and deprive a vast majority of citizens of the benefits of such global economic activity.

But until we abandon democracy (voting out governments), we have power if we choose to use it. We can force changes in the political system so that it works more for us and not the top-end-of-town.

Perhaps the anger now being unleashed is a start of that fightback.

The problem is that the Left is not leading the charge. It is leaving that to the crazy popularists while it crafts ever more ridiculous arguments to justify ‘austerity lite’ type policies to make them look responsible.

The reference group they seek to appeal to though is the neo-liberal elites – which means the Left is going nowhere.

We can have our iPhones and full employment!

The series so far

This is a further part of a series I am writing as background to my next book on globalisation and the capacities of the nation-state. More instalments will come as the research process unfolds.

The series so far:

1. Friday lay day – The Stability Pact didn’t mean much anyway, did it?

2. European Left face a Dystopia of their own making

3. The Eurozone Groupthink and Denial continues …

4. Mitterrand’s turn to austerity was an ideological choice not an inevitability

5. The origins of the ‘leftist’ failure to oppose austerity

6. The European Project is dead

7. The Italian left should hang their heads in shame

8. On the trail of inflation and the fears of the same ….

9. Globalisation and currency arrangements

10. The co-option of government by transnational organisations

11. The Modigliani controversy – the break with Keynesian thinking

12. The capacity of the state and the open economy – Part 1

13. Is exchange rate depreciation inflationary?

14. Balance of payments constraints

15. Ultimately, real resource availability constrains prosperity

16. The impossibility theorem that beguiles the Left.

17. The British Monetarist infestation.

18. The Monetarism Trap snares the second Wilson Labour Government.

19. The Heath government was not Monetarist – that was left to the Labour Party.

20. Britain and the 1970s oil shocks – the failure of Monetarism.

21. The right-wing counter attack – 1971.

22. British trade unions in the early 1970s.

23. Distributional conflict and inflation – Britain in the early 1970s.

24. Rising urban inequality and segregation and the role of the state.

25. The British Labour Party path to Monetarism.

26. Britain approaches the 1976 currency crisis.

27. The Left confuses globalisation with neo-liberalism and gets lost as a consequence

The blogs in these series should be considered working notes rather than self-contained topics. Ultimately, they will be edited into the final manuscript of my next book due later in 2016.

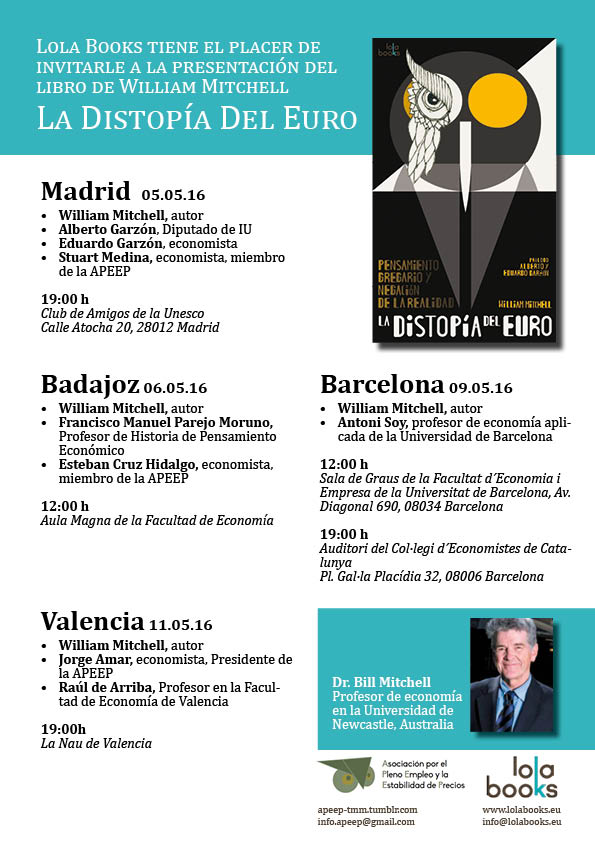

Upcoming Spanish Speaking Tour and Book Presentations – May 5-13, 2016

Here are the details of my upcoming Spanish speaking tour which will coincide with the release of the Spanish translation of my my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published in English May 2015).

You can save the flyer below to keep the details handy if you are interested. All events are open to the public who are encouraged to attend.