Spanish government discretionary fiscal deficit rises and real GDP growth returns

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2016-05-06

I am off to Spain in a few weeks to undertake a lecture tour associated with the publication of a Spanish translation of my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (see details below if you are interested). I noted by way of passing in a blog last week that a recent article in Spain’s highest-circulation newspaper El País (March 31, 2016) – Public deficit for 2015 comes in at 5.2%, exceeding gloomiest forecasts. The latest data shows that the Spanish government is in breach of Eurozone fiscal rules and is growing strongly as a result. Those who claim that Spain demonstrates how fiscal austerity can promote growth should examine the data more closely. The reality is that as growth has returned (albeit now moderating again), the discretionary fiscal deficit (that component of the final deficit that reflects the policy choices of government) has increased. Government consumption and investment spending has supported the return to growth, which had collapsed under the burdens of fiscal austerity between 2010 and 2013. Spain demonstrates how responsible counter-cyclical fiscal policy works.

On February 18, 2009, the European Commission issued an – Excessive Deficit Report – citing Spain’s fiscal position under Article 104(3) of the Treaty.

The European Commission writes:

Article 104 of the Treaty lays down an excessive deficit procedure (EDP). This procedure is further specified in Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 “on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure”, which is part of the Stability and Growth Pact. According to Article 104(2) of the Treaty, the Commission has to monitor compliance with budgetary discipline on the basis of two criteria, namely: (a) whether the ratio of the planned or actual government deficit to gross domestic product (GDP) exceeds the reference value of 3% (unless either the ratio has declined substantially and continuously and reached a level that comes close to the reference value; or, alternatively, the excess over the reference value is only exceptional and temporary and the ratio remains close to the reference value); and (b) whether the ratio of government debt to GDP exceeds the reference value of 60% (unless the ratio is sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace).

So Spain was brought into the EDP by dint of its fiscal deficit exceeding the 3 per cent rule (its public debt ratio at the time was around 39.8 per cent of GDP – under the threshold).

On April 27, 2009, the – European Council Decision – concluded that despite the “projected GDP contraction” of 2 per cent over 2009, the “the deficit criterion in the Treaty is not fulfilled” and as such “an excessive deficit exists in Spain”.

For the next several years, the technocrats in the European Commission and in the Spanish government toiled away with reports and analysis – see Spain Ongoing procedure – for the enormity of this waste of resources and blind obediance to neo-liberal Groupthink.

The European Council decision in April 2009 gave Spain until 2012 to “correct the excessive deficit”. A bit later (‘can down the road’) the Council revised the recommendation because of the “sharp deterioration in the growth outlook in the wake of the global economic and financial crisis had major negative budgetary implications” and extended the deadline for correction to the end of 2013.

Then on July 10, 2012, the Council extended the deadline out to the end of 2014 given the “unexpected adverse economic events with major unfavourable consequences for government finances had occurred after the adoption of the Council Recommendation … In particular, a worsening in the growth outlook and the shift to a less tax-rich growth composition”.

The “unexpected adverse economic events” were only unexpected by them. The situation in 2009 was fairly clear – it was going to be a very deep recession and the fiscal rules set by the mindless Maastricht Treaty would be blown out of the water by the cyclical impacts on government fiscal parameters alone.

So at the July 10, 2012 meeting, the Council determined that:

In order to bring the headline government deficit below the 3 % of GDP reference value by 2014, Spain was recommended to deliver an improvement of the structural balance of 2,7 % of GDP in 2012, 2,5 % of GDP in 2013 and 1,9 % of GDP in 2014 …

The – European economic forecast – Spring 2012 – that those targets were derived from were uniformly poor and understated the contraction in the Spanish economy.

Things turned sour.

The Spring forecasts had Spain contracting by 1.3 per cent in 2012 and only 0.3 per cent in 2013. The reality was quite different. Spain contracted by 2.6 per cent in 2012 and 1.7 per cent in 2013 – quite some difference!

On June 21, 2013, the European Commission released an updated report – Council recommendation to end the excessive deficit situation – which acknowledged that:

The deterioration in the macroeconomic outlook is partly linked to additional consolidation measures included in the 2013-14 budget plan and the 2013 budget being taken into account.

In other words, they got it wrong, imposed pro-cyclical fiscal cuts and the economy contracted by more than they had expected. Amazing really!

The fiscal deficit increased and all the European Commission was able to say was that:

… the estimated change in the structural balance was severely affected by unexpected revenue shortfalls …

They must live in a state of continual surprise in the EU towers in Brussels – they area always being confronted with “unexpected” occurrences.

As day follows night, Blind Freddy could have predicted more accurately than the European Commission technocrats.

For the many overseas readers, Blind Freddy is an Australian character (fictional) who is “supposed to have little or no perception”.

As the Wiktionary tells us “what blind Freddy can see (understand) must be very obvious”.

On October 1, 2013, the European Commission entered what it called the – Economic Partnership Programme – with Spain.

It was more fluff from an organisation that excels in writing long reports (this one was 58 pages) that are based on some previous reports with dates and parameters altered a bit and lots of technical talk that amounts to nothing added.

It continued to claim that “it was still necessary to maintain fiscal consolidation in order to continue on the path to reducing the public deficit” even thouse there remained an “adverse economic situation and uncertainty about the recovery of the European economy, which impacted the growth of the Spanish economy”.

The new date for Spain to meet the fiscal rules was extended to 2016 and the ‘smoke and mirrors’ told us that pushing out the deadline from 2013 (in the first instance) to 2016 (the latest deadline) should not be seen as “a relaxation of consolidation efforts, given that the structural effort to be done is not less than that presented in the previous Stability Programme, and is even more for 2013”.

Now the fiscal deficit targets were -5.8 per cent of GDP for 2014, -4.2 per cent by 2015, and -2.8 per cent of GDP by 2016 – thus complying with the fiscal rules under the stability and growth pact. At the time these targets were formulated the deficit was around 6.5 per cent of GDP.

So a heap of austerity measures were outlined for Spain to follow, irrespective of the continuation of elevated levels of unemployment, particularly among Spain’s youth.

At that time, Spain’s unemployment rate was 26.1 per cent and the youth (under 25 years) unemployment rate was 55.5 per cent.

The European Commission was for the time happy that the austerity was sufficient. They said on November 15, 2013 that Spain had “taken effective action and that … no further steps in the excessive deficit procedure are needed at present”.

We would wait until this year (2016) for the next assessment.

2016 was to be the new ‘witching hour’ for Spain – the year that they have to comply with the EDP or else. It will, of course, be or else, given that there wasn’t a ‘snowball’s chance in hell’ that Spain would comply with the rules.

And on March 9, 2016, the European Commission spat the dummy again and in the report – Commission Recommendation regarding measures taken by Spain in order to ensure a timely correction of its excessive deficit – we learn that after considering “Spain’s 2016 draft budgetary plan”, the Commission concluded that Spain “was at risk of non-compliance with the provisions of the Stability and Growth Pact”.

After further toing-and-froing between Madrid and Brussels with revised plans submitted and more time and energy wasted the Commission concluded that the fiscal deficit in Spain would “narrow to 3.6% of GDP in 2016, above the 3% of GDP reference value of the Treaty and the recommended deficit target of 2.8% of GDP. There are thus risks to the timely correction of the excessive deficit”.

The Commission thus told Spain that it “should take measures to ensure a timely and durable correction of the excessive deficit, including by making full use as appropriate of the preventive and corrective tools set out in Spain’s Stability law to control for slippages at the sub- central government level from the respective deficit, debt and expenditure rule targets”.

But the reality seems to be different and once again the Commission’s forecasts were again way off the mark and thank goodness for that.

On March 31, 2016, the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain’s National Statistics Institute) published the latest quarterly non-financial accounts for the institutional sectors and the data for the – General Government Sector – revealed a 56,608 million euro deficit for Spain’s government sector.

That is equivalent to 5.2 per cent of GDP, much larger than the 4.2 per cent that the last deal with the European Commission stipulated (as above).

As El País reported:

Spain’s 2015 public deficit came in at 5.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) … The €56.6 billion shortfall means that Spain has exceeded its target of 4.2% of GDP agreed with the European Commission by around €10 billion …

Still, 2015 was also a year in which economic growth surpassed all forecasts and tax revenues jumped significantly.

The article doesn’t draw out the obvious causality – higher fiscal deficits courtesy of higher social spending in the regions, higher expenditure on health services, and some large scale public infrastructure projects have driven the higher growth.

Win-Win.

Why call the rise in the deficit above the fiscal rules as “exceeding gloomiest forecasts” just goes to show the bias in the reporting.

Q: When is a good thing gloomy?

A: When you are a neo-liberal sociopath in the Brussels political elite who looks out only for the top-end-of-town.

Spain’s return to growth has been touted as a big success story for austerity. But if you examine the data in detail something different emerges.

Clearly the final fiscal outcome is the difference between Receipts and Spending. We can write the final outcome as:

Actual Fiscal Balance = (Tax Receipts + Other Receipts) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Receipts and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the fiscal balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the final fiscal balance in any period will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the fiscal balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the fiscal balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the economic cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the fiscal balance goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the government in question has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. The presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

Please read – Structural deficits – the great con job! – for more discussion about these decompositions.

Now what do you think has been happening to the structural fiscal balance in Spain since 2013? For the austerity merchants to be able to claim that the recent real GDP growth in Spain has been the result of fiscal austerity, the structural balance would have to have fallen over this period.

The data shows otherwise. The following graph taken from the European Commission’s own – Annual macro-economic database – shows the actual fiscal outcome (red) for Spain from 2010 and 2015 (adjusted for the latest data for 2015 and the Commission’s estimate of the structural balance (blue) both as a percent of GDP (potential GDP in the case of the structural balance).

And remember that the European Commission’s estimate of the structural (or cyclically-adjusted) fiscal balance always errs on the side of too low – biased downwards – because it uses a flawed estimate of potential GDP. I explain that in the blog linked above.

The data shows that the structural deficit (that is, the discretionary component of government fiscal policy) increased between 2013 and 2015.

As Peter Bofinger remarked in his Op Ed (April 8, 2016) – Two views of the EZ Crisis: Government failure vs market failure – Spain which is held out:

… as an example of “successful consolidation” even increased its structural deficit from 2013 to 2015 by 0.6 percentage points. As a consequence, in 2015 Spain was the advanced economy with the second largest budget deficit, behind Japan. Thus, the end of the recession in the Eurozone is not the result of “successful consolidation” but of a silent paradigm change which stopped the procyclical austerity policy of the years 2010 to 2013.

Amen to that!

And if you examine the latest National Accounts data from INE, real GDP growth resumed in the September-quarter 2013 and peaked in the June-quarter 2015, and has since then started to decline.

The following graph shows the quarterly percentage real GDP growth (blue columns) for Spain from the June-quarter 2013 to the December-quarter 2015 and the contribution of public consumption expenditure to that growth in percentage points.

While real GDP is still 3.8 per cent below the peak in the June-quarter 2008, public spending has been an important part of the recovery process.

Further, over that time (2013-2015), real public gross fixed capital formation (investment) has risen by 6.9 per cent after falling dramatically in the austerity years of 2010 to 2013.

As El País the greater than expected fiscal deficit:

… is mostly due to the deficit racked up by Spain’s regions, and to Social Security expenses that went over budget …

… part of last year’s gap is due to one-off expenditures in places such as Valencia or Catalonia – where €1.3 billion of previously unreported expenses surfaced in October – and to further undisclosed spending of €200 million by the city of Zaragoza on prison construction and on a tramway project.

There was another unexpected layout of €2.2 billion on health services.

And the result?

El País say:

Still, 2015 was also a year in which economic growth surpassed all forecasts and tax revenues jumped significantly.

That is why the overall fiscal deficit has been falling but the structural deficit has been rising. An excellent example of counter-cyclical fiscal policy – the type that responsible governments pursue, irrespective of what the technocrats at the European Commission think.

Conclusion

Once again the data tells the story. The Spanish authorities might have decided to defy the European Commission because of the pressures of an election year at all levels of government.

That clearly led to some new spending initiatives and a slowdown in the sort of austerity cuts that Brussels desired.

The proof is in the pudding.

If the Spanish government now bows to pressure from Brussels to renew the austerity push, the expected result will be a further slowdown in real GDP growth in Spain.

But then the technocrats in Brussels will put out another big report claiming that there had been an “unexpected” slowdown in growth. The poor souls – continually being caught out by these unexpected events that Blind Freddy could predict in his/her sleep.

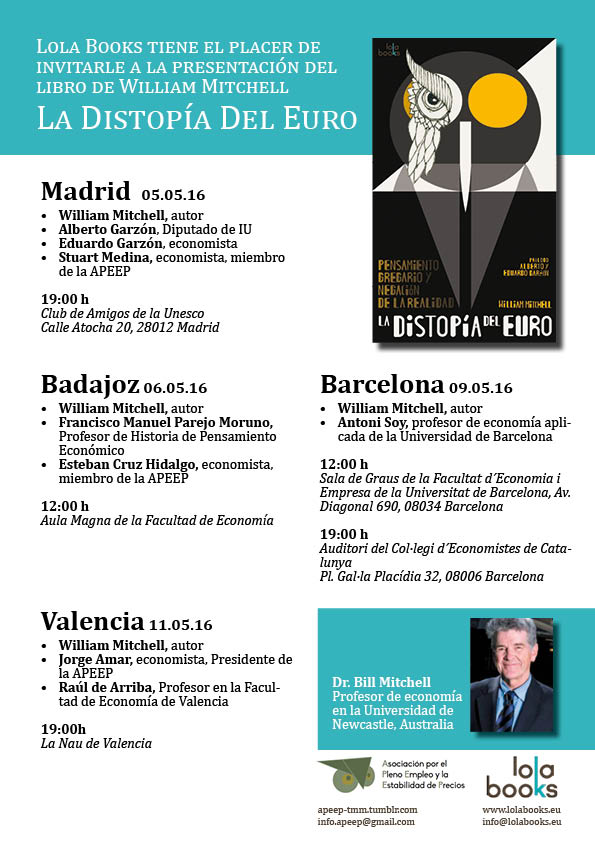

Upcoming Spanish Speaking Tour and Book Presentations – May 5-13, 2016

Here are the details of my upcoming Spanish speaking tour which will coincide with the release of the Spanish translation of my my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published in English May 2015).

You can save the flyer below to keep the details handy if you are interested. All events are open to the public who are encouraged to attend.

1. Madrid, May 5, 2016 – 19:00 at the Club de Amigos de la Unesco, Calle Atocha 20, 28012.

Speakers:

- William Mitchell, author

- Alberto Garzón, Diputado de IU

- Eduardo Garzón, economist

- Stuart Medina, economist and member of Asociación por el Pleno Empleo y la Estabilidad de Precios

2. Badajoz, May 6, 2016 at 12:00 at the Aula Magna de la Facultad de Economía.

Speakers:

- William Mitchell, author

- Francisco Manuel Parejo Moruno, Profesor de Historia de Pensamiento Económico

- Esteban Cruz Hidalgo, economist and member of APEEP

3. Barcelona, May 9, 2016 at 12:00 at Sala de Graus de la Facultat d ́Economia i Empresa de la Universitat de Barcelona, Av. Diagonal 690, 08034 Barcelona.

Speakers:

- William Mitchell, author

- Antoni Soy, profesor de economía aplicada de la Universidad de Barcelona

4. Barcelona, May 9, 2016 at 19:00 at Auditori del Collegi d ́Economistes de Catalunya, Pl. Gal·la Placídia 32, 08006 Barcelona

Speakers:

- William Mitchell, author

- Antoni Soy, profesor de economía aplicada de la Universidad de Barcelona

5. Valencia, May 11, 2016 at 19:00 at La Nau de Valencia.

Speakers:

- William Mitchell, author

- Jorge Amar, economist, President of APEEP

- Raúl de Arriba, Profesor en la Facultad de Economía de Valencia

FINALLY – Introductory Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Textbook

We have now published the first version of our MMT textbook – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice: an Introductory Text (March 10, 2016).

The long-awaited book is authored by myself, Randy Wray and Martin Watts.

It is available for purchase at:

1. Amazon.com (60 US dollars)

2. Amazon.co.uk (£42.00)

3. Amazon Europe Portal (€58.85)

4. Create Space Portal (60 US dollars)

By way of explanation, this edition contains 15 Chapters and is designed as an introductory textbook for university-level macroeconomics students.

It is based on the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and includes the following detailed chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: How to Think and Do Macroeconomics Chapter 3: A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism Chapter 4: The System of National Income and Product Accounts Chapter 5: Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds Chapter 6: Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money Chapter 7: The Real Expenditure Model Chapter 8: Introduction to Aggregate Supply Chapter 9: Labour Market Concepts and Measurement Chapter 10: Money and Banking Chapter 11: Unemployment and Inflation Chapter 12: Full Employment Policy Chapter 13: Introduction to Monetary and Fiscal Policy Operations Chapter 14: Fiscal Policy in Sovereign nations Chapter 15: Monetary Policy in Sovereign Nations

It is intended as an introductory course in macroeconomics and the narrative is accessible to students of all backgrounds. All mathematical and advanced material appears in separate Appendices.

A Kindle version will be available soon (stay tuned for the announcement).

Note 1: There is a typographical mistake in the book which although not repeated might throw your understanding.

On Page 138, Equation 7.15a is written as

(7.15) Y = E = A + [c(1-t) – m]Y

and solving for Y is then stated to give

(7.16) Y[1 – c(1-t) – m] = A

however this should instead read Y[1 – c(1-t) + m] = A.

Thanks to Brian S. for picking this up.

Note 2: We are soon to finalise a sister edition, which will cover both the introductory and intermediate years of university-level macroeconomics (first and second years of study).

The sister edition will contain an additional 10 Chapters and include a lot more advanced material as well as the same material presented in this Introductory text.

We expect the expanded version to be available around June or July 2016.

So when considering whether you want to purchase this book you might want to consider how much knowledge you desire. The current book, released today, covers a very detailed introductory macroeconomics course based on MMT.

It will provide a very thorough grounding for anyone who desires a comprehensive introduction to the field of study.

The next expanded edition will introduce advanced topics and more detailed analysis of the topics already presented in the introductory book.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.