72% youth unemployment – the crowning glory of the neo-liberal infestation

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2013-08-11

It seems like everything is getting smaller in Germany. I read today that Germany’s longest word (63 letters) has been abandoned. It also seems that their jobs are getting smaller and more people are being forced into them. The so-called “mini-jobs”. Meanwhile Europe’s crowning glory and austerity’s greatest achievement lies a little south of the mini-job kingdom. Eurostat’s latest – Regional labour force data – tells us that in some regions in Spain and Greece, the unemployment rates of the 15-24 year olds have topped 70 per cent and will continue to rise. There are now an increasing chorus in the media from politicians and financial market types who are trying to dress all this up as good news. Apparently, the Greek share market is booming. The agenda is clear – if they can somehow convince the world that the devastation of Greece is “good news” then it will reduce the growing resistance to austerity that is starting to broaden the debate. The elites don’t want any moderation. So they have to re-construct devastation to appear to be bringing good outcomes. The madness continues. Tell the 15-24 year olds in Dytiki Makedonia that things are going along swimmingly! First, that 63-letter word. The Age reports (June 4, 2013) – Sixty-three-character word is now verboten that:

Germany’s longest word – Rindfleischetikettierungsuberwachungsaufgabenubertragungsgesetz, the 63-letter title of a law about beef – has ceased to exist.

That is a long word. Apparently, it was not in the dictionary but was in official usage.

What about this German word?

Austeritydoesnotgenerategrowthdespitewhattheneoliberalssaybutrathercausespovertyanddepression

That seems to be around 93 characters.

But other things are getting smaller in Germany as well.

The Wall Street Journal article (May 29, 2013) – ‘Minijobs’ Lift Employment But Mask German Weakness – tells us that the upbeat talk about Germany as a success surrounded by failure is somewhat mistaken.

It does have a relatively low unemployment rate (6.9 per cent in May 2013). But:

… nearly one in five working Germans, or about 7.4 million people, hold a so-called “minijob,” a form of marginal employment that allows someone to earn up to €450($580) a month free of tax.

Minijobs pay low wages and do not provide the standard statutory benefits (holiday pay etc).

The neo-liberal apologists claim the minijobs satisfy the preferences of workers for flexible casual work. But the reality is different.

They become just another rationing device when aggregate demand is too low and lead to rising inequality and diminished investment in human capital.

The official data shows that:

While Germany’s top earners among full-time workers who contribute to the social security system saw pay rise 25% between 1999 and 2010, salaries in the lowest quintile increased roughly 7.5% … After inflation of about 18% during that period, Germany’s lowest wages dropped significantly.

The minijobs were part of the Hartz reforms, which I briefly discuss below.

The neo-liberals also claimed they formed part of the “stepping stone” upgrading where a young person could first take a casual job and then progress up to more regular, high paid positions.

The evidence in Germany (and everywhere for that matter) disputes this claim.

The point is that part of the Euro crisis that is least reported is the way that Germany responded to the loss of its exchange rate. Previously, the Bundesbank had manipulated the Deutsch mark parity to ensure the German export sector remained very competitive. That is one of the reasons they became an export powerhouse. It is the same strategy that the Chinese are now following and being criticised for by the Europeans and others.

Once the Germans lost control of the exchange rate by signing up to the EMU they had to manipulate other “cost” variables to remain competitive.

So the Germans were aggressive in implementing their so-called “Hartz package of welfare reforms”. A few years ago we did a detailed study of the so-called Hartz reforms in the German labour market. One publicly available Working Paper is available describing some of that research.

The Hartz reforms were the exemplar of the neo-liberal approach to labour market deregulation. They were an integral part of the German government’s “Agenda 2010″. They are a set of recommendations into the German labour market resulting from a 2002 commission, presided by and named after Peter Hartz, a key executive from German car manufacturer Volkswagen.

The recommendations were fully endorsed by the Schroeder government and introduced in four trenches: Hartz I to IV. The reforms of Hartz I to Hartz III, took place in January 2003-2004, while Hartz IV began in January 2005. The reforms represent extremely far reaching in terms of the labour market policy that had been stable for several decades.

The Hartz process was broadly inline with reforms that have been pursued in other industrialised countries, following the OECD’s job study in 1994; a focus on supply side measures and privatisation of public employment agencies to reduce unemployment. The underlying claim was that unemployment was a supply-side problem rather than a systemic failure of the economy to produce enough jobs.

The reforms accelerated the casualisation of the labour market (so-called mini/midi jobs) and there was a sharp fall in regular employment after the introduction of the Hartz reforms.

The rapid increase in the minijobs is a reflection of these deep-seated changes and have created a situation where an increasing (and sizeable) proportion of German workers are now excluded from enjoying the benefits of national income growth in that nation.

The German approach overall had overtones of the old canard of a federal system – “smokestack chasing”. One of the problems that federal systems can encounter is disparate regional development (in states or sub-state regions). A typical issue that arose as countries engaged in the strong growth period after World War 2 was the tax and other concession that states in various countries offered business firms in return for location.

There is a large literature which shows how this practice not only undermines the welfare of other regions in the federal system but also compromise the position of the state doing the “chasing”.

But in the context of the EMU, the way in which the Germans pursued the Hartz reforms not only meant that they were undermining the welfare of the other EMU nations but also droving the living standards of German workers down.

And then the crisis emerged amidst all this.

I am giving a lecture in Darwin tonight on austerity – a triumph of ideology over evidence. I dug out some of the quotes that have been made along the way by big-noting politicians and others which have marked the austerity route over the last 4-5 years. There are, of-course, countless similar quotes that I could have drawn out.

Have a laugh at these prescient individuals.

President Obama was – Interviewed on C-SPAN on May 22, 2009. Part of the conversation went like this:

C-SPAN host Steve Scully: You know the numbers, $1.7 trillion debt, a national deficit of $11 trillion. At what point do we run out of money?

Obama: Well, we are out of money now. We are operating in deep deficits, not caused by any decisions we’ve made on health care so far … We can’t afford it. We’ve got this big deficit

Then there was the George Osborne – Mais Lecture – A New Economic Model – on February 24, 2010 where we learned that:

Perhaps the most significant contribution to our understanding of the origins of the crisis has been made by Professor Ken Rogoff, former Chief Economist at the IMF, and his co-author Carmen Reinhart …

The latest research suggests that once debt reaches more than about 90% of GDP the risks of a large negative impact on long term growth become highly significant.

Right on the mark with our Excel spreadsheet Mavens.

And some more Ricardian wisdom from the same speech:

Those who recommend delay argue that when private demand is weak, cutting government spending too quickly risks undermining the recovery … [But] … why it is that private demand is weak.

Modern economics understands the importance of expectations and confidence. Businesses and individuals look to the future, and while they are not the perfectly rational creatures assumed by the theory of Ricardian equivalence, uncertainty over the future paths of tax rates and government spending does play an important role in their behaviour.

This is particularly true when it comes to consumer spending and business investment … a credible fiscal consolidation plan will have a positive impact through greater certainty and confidence about the future.

His boss, David Cameron must have been taking economics lessons off Osborne, because on January 27, 2011 in his – address – to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, the British Prime Minister said:

Those who argue that dealing with our deficit and promoting growth are somehow alternatives are wrong. You cannot put off the first in order to promote the second.

And we couldn’t leave the insights provided by the President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy in a – Speech to the European Parliament – on March 13, 2012:

One front is fiscal consolidation. Another is the growth and employment agenda. Some claim that these two are contradictory. It is our job to make sure that they are not.

And Angela got in on the act to with her – press agent – reporting on the results of a video conference call ahead of the G8 summit meeting with EU Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso and Herman Van Rompuy, president of the EC Council on May 17, 2012:

There was a high level of agreement that fiscal consolidation and growth are not contradictions, but rather both are necessary

On March 7, 2013, the British Prime Minister perhaps got a bit excited (given Choate’s response) when disclosing what he considered the – views of the Office of Budget Responsibility – in the UK were:

They are absolutely clear that the deficit reduction plan is not responsible; in fact, quite the opposite.

And Olli, never one to take a back seat wrote a – Letter – to the EC Finance Ministers on February 13, 2013 which contained the following:

… recall that public debt in the EU has risen from about 60% of GDP before the crisis to around 90% of GDP. And it is widely acknowledged, based on serious academic research, that when public debt levels rise above 90% they tend to have a negative impact on economic dynamism, which translates into low growth for many years. That is why consistent and carefully calibrated fiscal consolidation remains necessary in Europe.

Clearly extolling the Excel spreadsheet skills of Ken and Carmen.

And so it goes.

But what about this quote from a 2011 paper which appeared in the – Regional Economist – which is a journal published by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank:

… it is important to remember that the government differs critically from businesses and individuals …

As the sole manufacturer of dollars, whose debt is denominated in dollars, the U.S. government can never become insolvent, i.e., unable to pay its bills … In this sense, the government is not dependent on credit markets to remain operational.

Moreover, there will always be a market for U.S. government debt at home because the U.S. government has the only means of creating risk-free dollar-denominated assets …

Together with the unusually high, but manageable, level of the current debt, these facts imply that the current U.S. government can wait out any short-term economic developments until long-run growth is restored … Further, without an immediate need to drastically reduce the debt, the mechanism between high debt and slow growth loses most of its credibility.

[Reference: Fawley, B.W. and Juvenal, L. (2011) 'Why Health Care Matters and the Current Debt Does Not’, The Regional Economist, October]

The last quote seems to tell a different story – and it is one that the likes of Cameron, Osborne, the litany of European elites, and the rest of them should take time to learn.

Anyway, put all this together and you can see what these characters have created.

This graph (using the latest Eurostat data) shows the evolution of unemployment rates for youth (15-24 years) from 1983 to April 2013.

The next Table shows the unemployment rates for youth (15-24 years) for NUTS2 Regions for Greece and Spain at 1999 and 2012 (with the Change being the percentage point change between 1999 and 2012). They are ranked from highest to lowest as at 2012. In the first few months of 2013, the levels have deteriorated further.

These are Depression level numbers and will ensure the legacy of the policy failure spans several generations.

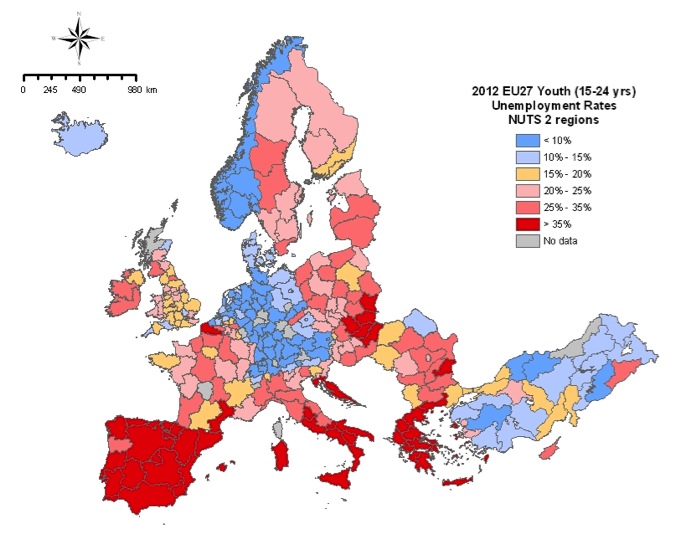

We produced a map (thanks to Michael in CofFEE) of the unemployment rate situation for youth in the EU as at 2012. The red areas are for unemployment rates above 35 per cent. The spatial clustering is highly significant and the spill-overs between the regions strong. That tells me that there is a systematic factor operating on a spatial basis – and I don’t think there has been an outbreak of laziness in any spatially concentrated form.

I was thinking about this data when I read this article in the Financial Times (May 30, 2013) – Greece’s good news goes largely unreported.

The article is part of an emerging chorus coming from the neo-liberals about how good things are becoming in Greece and soon we will hear the same about Spain and the whole monetary union.

The author of this particular gem is a so-called “strategist on the markets insight team” at a large investment fund. I presume they have some trades on that need the markets to think a growth outbreak is about to occur in Greece.

Why else would she write such drivel?

Apparently, the Athens Composite, a share index is “the best performing stock market index in Europe over the past year” which according to the author is a sign that recovery is about to become endemic in Greece.

She thinks this is all about a “global re-risking investment theme” (whatever that is in English) where:

… if Greece can present itself as a recovering economy, having taken the medicine of fiscal austerity and supply-side reform, then the reform agenda of the European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund will be given a further boost. By the same token, if Greece stumbles, other peripheral eurozone nations may be encouraged to delay supply-side changes

The ECB took care of the bond market boycott of Greek debt. That is not a problem. The problem is a chronic lack of aggregate demand and a rapid hollowing out of everything that an advanced economy would consider to be the pre-requisites of development.

The author claims that while the labour market remains weak, the attack on wages and conditions will improve competitiveness.

I showed in this blog – It’s all been for nothing – that is, if we ignore the millions of jobs lost etc – that international competitiveness in Greece is now lower not higher than it was before the crisis.

Following the crisis, the general tendency has been for real effective exchange rates to decline. However, the real effective exchange rate for Greece was higher in April 2013 (Index value = 101.6) than in January 2008 (Index value = 100) as the crisis was developing.

By comparison, the real effective exchange rate for Germany is now at 93.5. For the euro area overall the index is now at 91.9. Of the peripheral nations, only Ireland has seen a substantial drop in its real effective exchange rate (now at 88.7).

The rest of the so-called PIIGS have seen their real effective exchange rate fall only marginally during the austerity period. the index values as at April 2013 were staying 99.3, Portugal 98.2, and Italy 98.2.

So it is hard to square that against the FT article’s rhetoric that:

…. average unit labour costs have declined 14 per cent since the 2009 peak. The effect of this, together with weak domestic demand, has been a steady improvement in the current account deficit, which fell to 5 per cent in September 2012, from 16 per cent in 2009. Tackling the persistent current account deficit is key to long-term growth, and to debt sustainability, so this is welcome news.

The following graph (using IMF WEO data) shows the annual percentage change in real imports (blue) and real exports (red) from 2005 to 2012. This is hardly a sign that there is an explosion of exports going on as implied by the FT article.

The so-called “steady improvement” has largely come from a dramatic decline in imports, which reflects the Depression that the economy has been driven into by the elites.

It represents a dramatic collapse in standards of living in that nation.

She goes on to talk about the “headcount reductions in the civil service and the liberalisation of regulated professions, tourism and much of the retail sector” and the privatisation of state-owned enterprises etc as “good news”.

As an after thought she tells us that the fire sale of state assets is only likely to raise “half of what was initially projected, but at least some progress is being made”. Sure, the public wealth is being taken over by rich elites who get it at bargain prices. And in the meantime the phalanx of lawyers and management consultants employed to broker the sales make a fortune.

That is “good news”.

The clear intent of the conservatives and their media lackeys and the hangers-on in the financial markets is to present the worst as “good news”. It suits them to do that because as the FT author tells us:

That may help convince investors that the eurozone can embrace supply-side reform and need not be hostage to economic elites. None of this is to trivialise the risks, which remain considerable, but it does show that sometimes the reality is better than the dramatic headlines might suggest.

The agenda is clear.

But the reality is that 72 per cent (and rising) of the 15-24 years olds in some Greek regions cannot find work. They are facing a lifetime of disadvantage. They will have unstable work histories if they ever get work.

They will be at high risk of developing physical and mental maladies. They will create unstable families and perpetuate the disadvantage.

This “good news” will reverberate for generations.

Perhaps the financial markets will clean up again in Greece. But the fabric of the society will be damaged forever and the damage is going to mount as the crisis continues.

The weak labour market is where concentration should be focused not what the wealth shufflers are doing on the Athens Composite.

Conclusion

And then in the UK, the Opposition Chancellor demonstrated yesterday that he has well and truly lost it and his leader should sack him immediately.

The UK Guardian article yesterday (June 3, 2013) – As Labour’s iron man, Ed Balls could do the trick – related how Ed Balls would cut spending hard under a Labour government.

The journalist Polly Toynbee assessed his contribution as being an “impressive speech set out a credible economic plan, tough as titanium – too tough for some Labour tweeters”. Which tells me she knows nothing about economics.

The UK needs a substantial increase in the Budget deficit at present and under the current economic trajectory, that will not alter by the time the people vote to elect the next national government.

The problem is that they have no-one credible to vote for in the UK. All sides of politics are now infested with the neo-liberal disease of ignorance and malice.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.