It’s all been for nothing – that is, if we ignore the millions of jobs lost etc

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2013-08-11

The fiscal austerity imposed on the southern European nations such as Greece and Spain has been imposed by the Troika with two justifications. First, that the private sectors in these nations would increase spending as the public sector cut spending because they would no longer fear the future tax hikes associates with rising deficits (the Ricardian argument). The evidence is clear – they haven’t. The second argument was that massive cost cutting (the so-called internal devaluation) would improve the competitiveness of the peripheral nations, close the gap with Germany and instigate an export bonanza. It was all about re-balancing we were told. The evidence for that argument is clear – it was a lie. The massive impoverishment of these nations and the millions of jobs that have been lost and the destruction of a future for around 60 per cent of their youth (who want to work) has all been for nothing much. As was obvious when they started. At the onset of the crisis, many graphs appeared in official publications from various organisations including the OECD, the IMF, the World Bank, the European commission, and the list goes on, which showed movements in the real effective exchange rate for the peripheral Euro nations compared to Germany.

The graphs were typically indexed by the year 2000 and by 2008 or 2009 they showed that the gap between the PIIGS and Germany had opened widely with the real effective exchange rates for the PIIGS rising and for Germany falling.

The conclusion was that there was a major gap in trade competitiveness between Germany and its Euro-area partners due to excessive wages, poor productivity, and excessive regulation in the peripheral nations.

There was barely a whisper about the fact that Germany was suppressing domestic real wages growth and therefore stifling domestic demand. There was barely a whisper that the only way Germany was growing was to export to the rest of Europe. The emphasis was all on the over-spending nature of the peripheral nations even though that so-called “over-spending” allowed Germany to grow while reducing the real standards of living for its own workforce.

It beggared belief how people have tolerated this one-sided construction in Europe. The blame was always sheeted home to the weaker nations.

Given this construction, it became very easy for the Troika to argue that a major internal devaluation was required in the peripheral nations to redress the competitiveness gap.

It wasn’t surprising that this argument also was used to justify attacks on the key targets of the free market lobby: public sector employment, welfare payments, trade unions, and wages generally.

It also wasn’t surprising that the attacks on the peripheral nations were reinforced by long-held cultural and ethnic stereotypes about the profligacy or laziness of the fat Greeks or unreliable Italians, or warm-blooded Spaniards or the dim-witted Irish.

After all if you want to mount a massive attack on the living standards of a nation without the democratic consent of its people then it is essential to demonise those same people.

Blame the victims has been a hallmark of the neo-liberal era. Think about how the unemployed are reconstructed by the vile nomenclature that government agencies use to be dole bludgers, cruisers, job snobs, lazy, inveterate beach bums, etc

Divide and conquer has been one crude strategy the neo-liberals have used to break up worker solidarity.

And so fiscal austerity was imposed. Harsh cutbacks. Jobs destroyed in their millions. Pension entitlements hacked. Poverty rates rose. In some nations, 55-60 per cent of the youth are unemployed, most of whom will face a bleak future – without education, without skill development and without workforce experience. Many will become junkies, thieves and dissidents – and who could blame them.

The two promises outlined in the introduction were clear.

First, the private sector would spend as the public sector cut spending because they would no longer fear the future tax hikes associates with rising deficits (the Ricardian argument)

Second, that the cost cutting (the so-called internal devaluation) would improve the competitiveness of the peripheral nations, close the gap with Germany and instigate an export bonanza.

On March 20, 2008, the IMF released its – Staff Report for the 2007 Article IV Consultation Greece – where after a so-called extensive consultation that:

The Greek economy has been buoyant for several years and growth is expected to remain robust for some time. The risks to the outlook are tilted to the downside. In the near term, risks stem from a weaker external environment and a potential liquidity squeeze of banks. Over the longer-term, a persistent loss of competitiveness raises the prospect of a prolonged period of slow growth. Averting this risk requires improving cost competitiveness through wage moderation, an environment that encourages product upgrading, and a broadened effort to reform product and labor markets.

On May 25, 2009, the IMF released the next – Staff Report for the 2007 Article IV Consultation Greece – and claimed that “fiscal consolidation cannot be postponed” – that “There is no room for fiscal stimulus” – and that tax hikes, public service cuts, privatisation, wage cuts and social security reform were necessary to “restore competitiveness”.

A year later, on May 2, 2010 the IMF continued claiming more cuts were required because the “economy needs to be more competitive” (Source).

As each year passed, the flawed growth forecasts were just adjusted to be positive in the next year. Then the next. And so it went.

As I have noted in the past, a surgeon who delivered such damaging outcomes would be jailed for malpractice. The IMF has a criminal record by any measure of standards.

Neither of the promises have been delivered. It is clear there has been no major private sector spending burst. As unemployment has risen and aggregate demand falling further consumers and firms are bunkering down. There will be no widespread consumer revival while the threat of unemployment remains. Firms will not enter a new investment phase while the sales prospects are so bleak.

The austerity economists should have run up a psychologist or consulted some sociologist or two to learn about human behaviour.

But what about the export led bonanza? I have noted some comments occasionally here that the rebalancing of competitiveness is finally starting to work in the Eurozone.

My reply is – the evidence doesn’t tell me that.

Before I consider that though a point needs to be clear. Eventually, these scorched earth nations will grow again. At some point someone will see an investment opportunity and the multipliers will take care of the rest. No-one doubts that. But the damage that will have been caused in the meantime will resonate for decades. And when you realise these nations could have avoided the recession altogether with some nimble fiscal initiatives then it beggars belief that they would have chosen the route they have taken.

But what about competitiveness?

The Bank of International Settlements publish monthly Effective exchange rate indices – for 61 countries from January 1994.

You can learn about this data from their publication – The new BIS effective exchange rate indices – which appeared in the BIS Quarterly Review, March 2006.

There was an earlier publication – Measuring international price and cost competitiveness – which appeared in the BIS Economic Papers, No 39, November 1993.

Real effective exchange rates provide a measure on international competitiveness and are based on information pertaining movements in relative prices and costs, expressed in a common currency. Economists started computing effective exchange rates after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s because that ended the “simple bilateral dollar rate” (Source).

The BIS say that:

An effective exchange rate (EER) provides a better indicator of the macroeconomic effects of exchange rates than any single bilateral rate. A nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is an index of some weighted average of bilateral exchange rates. A real effective exchange rate (REER) is the NEER adjusted by some measure of relative prices or costs; changes in the REER thus take into account both nominal exchange rate developments and the inflation differential vis-à-vis trading partners. In both policy and market analysis, EERs serve various purposes: as a measure of international competitiveness, as components of monetary/financial conditions indices, as a gauge of the transmission of external shocks, as an intermediate target for monetary policy or as an operational target.2 Therefore, accurate measures of EERs are essential for both policymakers and market participants.

If the REER rises, then we conclude that the nation is less internationally competitive and vice-versa.

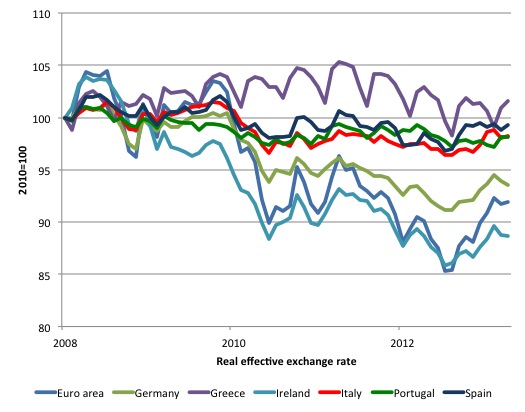

The following graph shows movements in real effective exchange rates since January 2008 until April 2013 for selected Eurozone nations and the Euro area overall.

Following the crisis, the general tendency has been for real effective exchange rates to decline. However, the real effective exchange rate for Greece was higher in April 2013 (Index value = 101.6) than in January 2008 (Index value = 100) as the crisis was developing.

By comparison, the real effective exchange rate for Germany is now at 93.5. For the euro area overall the index is now at 91.9. Of the peripheral nations, only Ireland has seen a substantial drop in its real effective exchange rate (now at 88.7).

The rest of the so-called PIIGS have seen their real effective exchange rate fall only marginally during the austerity period. the index values as at April 2013 were staying 99.3, Portugal 98.2, and Italy 98.2.

Now consider the next graph, which compares the peripheral nations of the Eurozone with Iceland.

Of-course, the fundamental differences between the Eurozone nations and Iceland is threefold: (a) Iceland issues its own currency while the other nations use a foreign currency; (b) Iceland enjoys a floating exchange rate; (c) Iceland sets its own interest rate.

These are the differences which define whether a nation is sovereign in its own currency or not.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) indicates that nations that the sovereign in their own currencies will enjoy better prospects, if the government deploys the characteristics of that currency monopoly to advance public purpose in an appropriate way.

Consider the scale of the real effective exchange rate drop for Iceland compared to even Ireland. And while you’re doing that think about Greece.

The Euro nations have not succeeded in significantly increasing their competitiveness despite massive cuts. Internal devaluation is not an effective way to increase international competitiveness. The costs of such a strategy are too high and society breaks down before you get close to the goal.

For Iceland, the work has been done by the exchange rate moving. Less painful and more effective.

The depreciation in Iceland created a major change in the trade sector. Their exports became much cheaper and demand grew rapidly at the same time as import demand fell because of the rise in prices in the newly restored local currency.

For analysis of how Argentina allowed its exchange rate to drop significantly in 2002, please read my blog – A Greek exit would not cause havoc – for more discussion on this point.

Note that the real effective exchange rate in Iceland evened out after its initial plunge. That is a common pattern. After an initial plunge, the nominal exchange rate stabilises as growth returns.

While the dogma is that a nation that cuts its wages will improve competitiveness is rife, the reality is clearly different.

The problem is that if a nation attempts to improve its international competitiveness by cutting nominal wages in order to reduce real wages and, in turn, unit labour costs it not only undermines aggregate demand but also may damage its productivity performance.

If, for example, workforce morale falls as a result of cuts to nominal wages, it is likely that industrial sabotage and absenteeism will rise, undermining labour productivity.

Further, overall business investment is likely to fall in response in reaction to the extended period of recession and wage cuts, which erodes future productivity growth. Thus there is no guarantee that this sort of strategy will lead to a significant fall in unit labour costs.

There is robust research evidence to support the notion that by paying high wages and offering workers secure employment, firms reap the benefits of higher productivity and the nation sees improvements in its international competitive as a result.

Conclusion

No-one is denying that economies such as the Greek economy have structural issues which bias them to higher inflation.

The point is clear that these problems are never going to be solved more quickly by impoverishing the nation. A freely floating exchange rate (which means exit from the Euro) will be a more effective way of attenuating the imbalances that have emerged between northern and southern Europe with respect to trade.

However, the real bonus that an exit would bring is that nations such as Greece can then unambiguously concentrate on a domestic growth strategy and put an end to its recession.

But in terms of the two promises – Ricardian growth responses and net export bonanza via increased competitiveness – neither have been delivered and we have enough data to conclude that categorically.

I have a long flight to catch – so ….

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.