Eurozone – what do they propose as an encore?

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2013-12-20

During the late 1980s and into the 90s when the Monetarists (mostly holed up in Britain) were boasting that the widespread privatisation and labour market deregulation strategies they had instigated were containing inflation and setting up their economies for sustained growth with reductions in unemployment my response was “what do they do they do for an encore”. It was obvious that if you scorched domestic demand and pushed up unemployment that the inflation rate would drop and the reduced imports would flatter the external balance. The question then was – what do you do next? Once growth returns in domestic demand rises on the back of increased income growth, imports start catching up and workers start demanding wage rises to make up for lost real income during the deflation and you end up with nothing much being achieved except for a extended period of lost real income, and rising inequality given the lower income groups carry the burden of the recession. The conservatives became slightly more astute in more recent years arguing that the recession provided the opportunity for nations to undergo radical restructuring so that growth could be driven by exports as a result of increased competitiveness. That’s the European model at the moment. Is it working? The IMF doesn’t think so. The IMF released its latest – World Economic Outlook (October 2013) – earlier this month and there was an interesting section – Box 1.3 External Rebalancing in the Euro Area – from pages 44-48. It didn’t get much attention and certainly very few commentators have picked up on it.

One who did was the ever-watchful Wolfgang Münchau who in his Financial Times article (October 27, 2013) – Optimism about an end to the euro crisis is wrong – referred to the IMF analysis.

I often disagree with what Wolfgang Münchau writes and his opening line is no exception:

Adjustment is the key to ending the eurozone crisis.

While it is peripheral to today’s blog, the Eurozone crisis goes well beyond adjusting external balances. The “adjustment” thesis is pure IMF rhetoric. Even if all the nations within the Eurozone achieve external balance the crisis will remain because massive increases in domestic demand are required in many countries to create employment and wipe out the devastating increase in unemployment.

While the source of the crisis was the financial instability wrought by the massive buildup in private debt and the failure of governments to regulate the financial sector appropriately, the reason the damage has been amplified in the Eurozone relates to the intrinsic flawed design of the monetary union.

The key to ending their Eurozone crisis is resolving those endemic flaws, which, as I’ve noted in the past, either require the creation of a truly federal fiscal capacity or a breakup of the monetary union. A related requirement is that the un-workable fiscal rules embodied in the Stability and Growth Pact be abandoned and member states be permitted to run appropriately scaled deficits to maintain domestic demand when a negative aggregate demand shock hits the European economy.

It is a combination of the Eurozone nations using a foreign currency (the Euro) and the issuers of that currency (the ECB) not permitting the nations to run appropriate deficits that is at the core of the Eurozone problem.

Making the nation’s more competitive will not overcome that endemic flaw.

It is possible (and we’re seeing it) that some growth will return to this beleaguered part of the World. It is also possible that exports could drive this growth as long as China, Japan and the US maintain sufficient deficit-supported growth in their own economies (which at present is the case). But unless the design flaws are addressed, the Eurozone nations are just a quarter away from the next major meltdown.

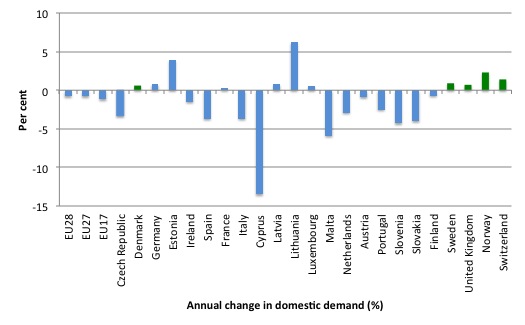

The following graph is taken from the latest – National Accounts – data provided by Eurostat and shows the annual growth in domestic demand (up to June-quarter 2013), which is the total amount of money that is spent on goods and services by the residents of the nation including imports. It excludes exports.

So it gives an indication of what conditions are like in the nation for the people and the companies.

The Eurostat data excludes some nations (such as Greece). The green bars are non-Eurozone nations. I have included the Latvia and Lithuania among the blue bars given that the koruna, lats, and the litas are all pegged to the Euro.

The picture is quite dire.

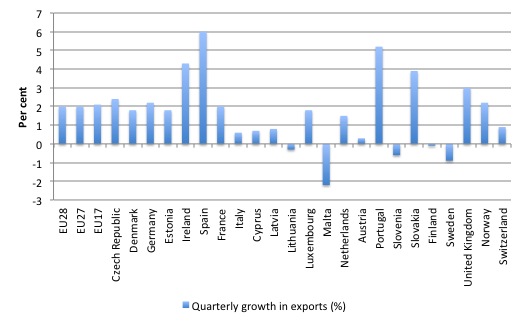

The next graph is what all of the European optimists are crowing about. It shows the quarterly growth in exports for the June-quarter 2013 for the same group of countries that were assembled in the last graph.

It is quite clear that in most nations shown exports are growing and for Spain and Ireland and Portugal one would conclude there has been significant growth.

But caution is required. Re-read this blog – Fiscal deficits in Europe help to support growth – which shows that recent measures of international competitiveness available from the Bank of International Settlements monthly Effective exchange rate indices – show that the Euro nations have not succeeded in significantly increasing their competitiveness despite massive cuts. Internal devaluation is not an effective way to increase international competitiveness. The costs of such a strategy are too high and society breaks down before you get close to the goal.

The following graph also tells you why the current growth in exports is unlikely to continue. It shows the Euro exchange rate (monthly) against the British Pound and the US dollar from January 2012 to September 2013. The base period is the first quarter of 1999 (100). The data is from the – ECB Data Warehouse.

It shows that the Euro has been strengthening significantly since the middle of 2012 (which some dips along the way). So any gains in the external balance coming from the recent growth in exports will be wiped out fairly quickly by these exchange rate movements.

Then you are left with the cyclical suppression (as a result of the domestic austerity) of import spending, which will bounce back as soon as there is any return to domestic growth.

I agree with Wolfgang Münchau’s assessment of the state of play in this regard. He says:

Optimists are saying that this process of regaining competitiveness is now taking place. Look at the success of the Spanish export sector or the fall in Greek wages. And, in any case, the eurozone economy is rebounding, which helps further.

This judgment is profoundly wrong. It is true that the crisis countries have brought down their current account deficits. Italy and Spain are now running surpluses. Since Germany and the Netherlands have not brought down their current account surpluses, the eurozone as a whole has moved from an almost balanced current account in 2009 to a surplus this year of 2.3 per cent of gross domestic product … In other words, the eurozone is adjusting at the expense of the rest of the world.

But while the eurozone is a fixed-currency regime internally, it is nothing of the sort externally. The currency does exactly what textbooks say it should: it keeps on rising, thus offsetting the improvements in the current account. Last week the euro rose to more than $1.38 against the dollar.

The assessment in the IMF World Economic Outlook also would suggest that all we are witnessing within the Eurozone are cyclical adjustment is driven by austerity rather than any substantial restructuring of the European economies.

In Box 1.3 (which starts on page 44 of the October WEO), we read that:

… current account balances in member countries with external deficits have improved significantly amid market pressure, whereas current account surpluses in other member countries have not declined because of sluggish domestic demand.

So nations such as Germany are retaining their mercantilist strategy of suppressing domestic real wages (that is, the living standards of its citizens) and running small fiscal surpluses which is keeping the growth of full-time, quality employment down and refusing to stimulate its trading partners.

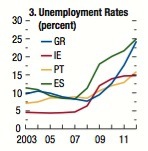

The other nations are reducing their external deficits mostly because imports are collapsing as a result of domestic recession and record unemployment rates.

The following graph comes from the IMF WEO (Figure 1.3.1, panel 3).

Commenting on this data, the IMF also recognise that:

… output remains below potential and unemployment rates are close to record highs in deficit countries, implying that further substantial adjustment is needed for external balance to be maintained when the crisis is over …

That is the meaning of the title of today’s blog.

It is one thing to close an external deficit with a massive increase in unemployment and the lost income that accompanies that level of job loss, but it is another thing to presume that the external position will remain unchanged once the unemployed start earning incomes again and resume their previous consumption habits (including import spending).

The IMF’s conclusion is that “is that continued adjustment by deficit countries (‘internal devaluation’) is needed to bolster their external competitiveness and to prevent a reemergence of large current account deficits as their economies recover”.

In other words, further retrenchments of living standards, security for workers, etc in the countries that have experienced massive jumps in unemployment, rising poverty rates and all the rest of the pathologies that accompany such states.

It is a real race to the bottom strategy and the bottom is looking bottomless the longer the crisis endures and the Euro elites refuse to recognise the design flaws in their monetary union.

But as the real exchange rate data from the BIS and the nominal exchange rate data from the ECB shows the race to the bottom doesn’t exactly lead to the deep structural changes in the trading positions of these recessed nations.

Wolfgang Münchau also notes that:

… the rise in the euro’s external value is that it makes the internal adjustment harder. The crisis countries need to lower their export prices but the higher value of the euro raises the prices of exports to outside the eurozone.

The IMF analysis shows that the internal adjustments across the Euro nations is mixed. For example, Irish unit labour costs had fallen in both the “tradables and nontradables sectors earlier than in the other euro area members” and there is some “recovery of output in the tradables sector, but it has not yet led to improved wages and employment”.

For “Portugal and Spain, output fell in the recent period and employment has continued to decline, with little in the way of wage cuts until recently”.

For “Greece, adjustments are being made through wage cuts and labor shedding in the absence of output recovery”.

Taken together, they conclude:

Overall, there have been no output gains except in Ireland, which reflects in part the general collapse of domestic demand in the euro area, and employment remains below precrisis levels in both the tradables and nontradables sectors.

Once again any of the observed changes in ULCs are being driven by the recessed cycle rather than any substantial rise in productivity.

The IMF ask “how much of the current account adjustments in the euro area will be lasting?” The conclusion is not very hopeful. They suggest that:

… cyclical factors explain a significant share of the current account reversals in these economies (especially in Greece and Ireland), whereas the impact of measured structural factors (potential output, demographics, and the like) has generally been modest except in a few countries, including Germany …

Which is exactly maintaining the status quo – Germany’s competitiveness will increase relative to the rest and growth will re-ignite all the internal trade imbalances. Germany will grow because imports in other nations will drive them (notwithstanding the German’s accusing the lazy southern nations of living beyond their means) and the Eurozone will be sitting in wait for the next world slump in aggregate demand.

Then it will all start again – but next time the residual pool of unemployment and the devastating alienation of Europe’s youth will be much higher than it was in 2007-08 – because the growth that will be necessary to bring the current mass unemployment down to pre-crisis levels is well beyond the Eurozone nations given the fiscal rules it has imposed.

Conclusion

All of this leads Wolfgang Münchau to conclude that:

In a monetary union adjustment is hard without any transfers and without a fiscal union. I know of no plausible plan how the eurozone can manage the dual feat of economic adjustment and debt sustainability within the straitjacket of official policy. And as long as such a plan does not exist, the crisis is not over.

Back to a focus on the design flaws in the monetary union – which is where the focus should be.

The deterioration in university standards around the world

Fellow MMT colleague Stephanie Kelton tweeted the following overnight about academic standards at UMKC:

Our History of Thought prof just told me that a student wrote that capitalism began with people buying sheep and selling deer.

Oh dear! Don’t shed too many tears.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.