The confidence tricksters in the economics profession

Bill Mitchell - billy blog » Eurozone 2013-12-20

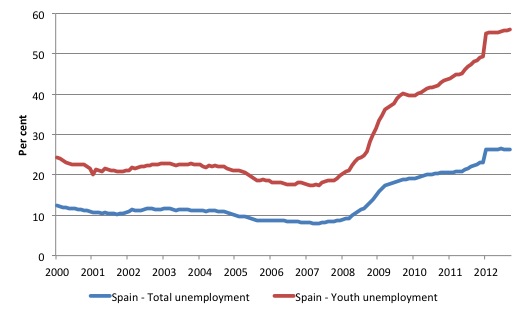

There was an extraordinary report in the Wall Street Journal last week (September 19, 2013) – Austerity Seen Easing With Change to EU Budget Policy – which considered the political machinations in Europe that may lead to the EU relaxing some of the harsh austerity measures that have deliberately pushed millions of Europeans onto the jobless queues. I say extraordinary because it shows how flaky the mainstream of my profession is and how they seem to think everyone else is stupid and as long as they dress up their so-called “analysis” in the opaque language of the cogniscenti, the general public will believe anything. This includes the proposition that underpins the on-going and harsh austerity programs in Europe that a reasonable definition of full employment in Spain, for example, is consistent with an unemployment rate of 23 per cent (and near to 60 per cent youth unemployment). They are trying to keep a straight face when they report that their estimates of full employment have moved from around 8 per cent unemployment to 23 per cent unemployment in a few years. It beggars belief and these confidence tricksters should be called to account. The following blogs are background to today’s blog:

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

A summary of the main points will help:

The federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa.

The budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government. So if the budget is in surplus we conclude that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

However, the complication is that we cannot then conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty is that there are automatic stabilisers operating.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the Budget Balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the Budget Balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the Budget Balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the Budget Balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into or is in deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation. I will come back to this later.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life

Things changed in the 1970s and beyond. At the time that governments abandoned their commitment to full employment (as unemployment rise), the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

NAIRU theorists then invented a number of spurious reasons (all empirically unsound) to justify steadily ratcheting the estimate of this (unobservable) inflation-stable unemployment rate upwards.

The NAIRU has been severely discredited as an operational concept but it still exerts a very powerful influence on the policy debate.

Further, governments have become captive to the idea that if they try to get the unemployment rate below the “estimated” NAIRU using expansionary policy then they would just cause inflation. I won’t go into all the errors that occurred in this reasoning. Our 2008 book – Full Employment Abandoned with Joan Muysken is all about this period.

Now I mentioned the NAIRU because it has been widely used to define full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then the mainstream concluded that the economy is at full capacity.

Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

But they still persist in using it because it carries the ideological weight – the neo-liberal attack on government intervention.

So they changed the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance to avoid the connotations of the past that full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels. Now you will only read about structural balances.

And to make matters worse, they now estimate the structural balance by basing it on the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending and thus concludes the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is.

They thus systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So they are trying to tell us that the business cycle moves around a fixed point – currently around 5 per cent unemployment – and above that the economy is operating with spare capacity and below it the economy is operating over full capacity.

The NAIRU is tied in with estimates of the Output Gap.

As I note in this blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – the problem is that the estimates of output gaps are extremely sensitive to the methodology employed.

They rely on an estimate of potential GDP, which is non-observable. It is clear that the typical methods used to estimate potential GDP reflect ideological conceptions of the macroeconomy, which are problematic when confronted with the empirical reality.

For example, on Page 3 of the CBO document – Measuring the Effects of the Business Cycle on the Federal Budget – we read:

… different estimates of potential GDP will produce different estimates of the size of the cyclically adjusted deficit or surplus …

CBO define Potential GDP as “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use.

So how do they estimate potential GDP? They explain their methodology in this document.

CBO say that they:

They start with “a Solow growth model, with a neoclassical production function at its core, and estimates trends in the components of GDP using a variant of a tried-and-tested relationship known as Okun’s law. According to that relationship, actual output exceeds its potential level when the rate of unemployment is below the “natural” rate of unemployment) Conversely, when the unemployment rate exceeds its natural rate, output falls short of potential. In models based on Okun’s law, the difference between the natural and actual rates of unemployment is the pivotal indicator of what phase of a business cycle the economy is in.

The resulting estimate of Potential GDP is “an estimate of the level of GDP attainable when the economy is operating at a high rate of resource use” and that if “actual output rises above its potential level, then constraints on capacity begin to bind and inflationary pressures build” (and vice versa).

So despite saying that their estimate of Potential GDP is “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use” what you really need to understand is that it is the level of GDP where the unemployment rate equals some estimated NAIRU.

Intrinsic to the computation is an estimate of the so-called “natural rate of unemployment” or the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment.

Given the history of estimates of the NAIRU, the “steady-state” unemployment across different nations has varied dramatically from time to time – with sudden rises projected for no apparent reason other than the actual unemployment has just risen. These estimates would hardly be considered “”high rate of resource use”. Similarly, underemployment is not factored into these estimates

The concept of a potential GDP in the CBO parlance is thus not to be taken as a fully employed economy. Rather they use the standard dodge employed by mainstream economists where the the concept of full employment is not constructed as the number of jobs (and working hours) which satisfy the preferences of the available labour force but rather in terms of the unobservable NAIRU.

The problem is that policy makers then constrain their economies to achieve this (assumed) cyclically invariant benchmark. Yet, despite its centrality to policy, the NAIRU evades accurate estimation and the case for its uniqueness and cyclical invariance is weak. Given these vagaries, its use as a policy tool is highly contentious.

The OECD’s method is outlined in – Long-term growth scenarios – which is Working Paper No. 1000 by Johansson et. al. (2013) published by the OECD Economics Department Working Papers series.

The IMF follow a similar method although the way they project the estimates can vary.

There is a Working Group within the European Commission’s Economic Policy Committee (EPC) called the – Output Gaps Working Group.

It say that the:

The Group is mandated to ensure technically robust and transparent potential output and output gap indicators and cyclically adjusted budget balances in the context of the Stability and Growth Pact. The group should as appropriate develop progressively the commonly agreed method for calculating output gaps. This is particularly important in view of the 2005 agreements on the Stability and Growth Pact.

I was amused at the “transparent” bit – which in any reasonable language tells us that there should be a raft of published material including time series data, technical manuals etc – to let us all know about the work of this important group.

I have sought such information with no success.

The Publication Page for the EPC lists its “10 latest publications” – the last being a 2011 Report on Aeging. The other reports go back to 2008 and are dominated by ageing and pension analysis. Standard scaremongering.

The latest report on estimating potential output and output gaps is 2004. Very transparent!

The problem is that this Group seems to be at the centre of why millions of Spaniards have been deliberately pushed out of work by the Troika (IMF, ECB and EC) in tandem with an obsequiously compliant Spanish polity.

Consider the following graph which shows the total and youth (15-24) unemployment rate in Spain from 2000 to 2013 (September). The data is from Eurostat.

Any reasonable interpretation of this graph and a knowledge that as the unemployment rates spiralled, real output growth collapsed, would lead to the conclusion that the post-2007 period is a cyclical event.

Structural events are typically slow moving. A nation doesn’t suddenly lose its productive capacity (unless there is an extraordinary event like a tsunami or earthquake or war). Labour forces do not suddenly alter their preferences between their desire to work and their desire to retire early, or work less, or “enjoy leisure”.

Labour forces do not suddenly become indolent. Inasmuch as these attitudinal changes ever occur, they occur over time and are not discernable on a month to month basis.

So it would be hard to consider the rise in unemployment in Spain from its average between 2000 and 2007 of around 10 per cent or 8.7 per cent between 2005 and 2007, to 16 per cent in early 2009 and 26 per cent or so in early 2012 could be explained in structural terms.

In other words, it would be extraordinary to assert that the NAIRU had risen in 3 short years from 8 per cent to 26 per cent. It might be that productive capacity has been wiped out and the inflation barrier is now hit at a real GDP level some 20 or more percent below the level of early 2008, but that doesn’t square with the real output gap estimates of the OECD or even the IMF.

Why does this all matter?

Let’s return to that Wall Street Journal article (September 19, 2013) – Austerity Seen Easing With Change to EU Budget Policy.

In that article by journalist Matthew Dalton we read that:

European finance officials tentatively approved a change to the region’s budget policies that is likely to lighten the austerity required of Spain and other countries hardest hit by the sovereign-debt crisis.

A reasonable person would consider that a policy change – a relaxation of austerity, which has crippled the Spanish economy and caused the unemployment crisis that is depicted in the graph above.

But that is not the way the European Commission officials are presenting it.

These zealots are trying to convince us that their policy structures are completely consistent and all that might have changed is that their estimates of the “structural deficit” could be revised.

The Stability and Growth Pact appended with the so-called Fiscal Compact in Europe now requires that EU governments maintain structural deficits “under 0.5% of a country’s gross domestic product” (more or less).

The actual deficit can be at 2 per cent (as in the SGP) but the structural component should be under 0.5 per cent.

Cue – the Output Gaps Working Group introduced above.

They have informed officials that deficits in the Eurozone are mostly structural in nature rather than cyclical, which defies other official data (say from the OECD and the IMF) and basic common understanding that it is the other way around.

The WSJ article says:

In a weak economy, with mass unemployment and many factories running at only a fraction of full capacity, government revenue is depressed and social spending is elevated.

The structural deficit in these circumstances will be lower than the actual deficit, representing the assumption that once the economy strengthens, the real deficit will naturally narrow, without cuts to government spending or tax increases that have proved politically toxic.

But Europe’s current method for calculating the structural deficit has determined that much of the budget deficits seen in the bloc’s weakest economies are structural, or built-in, not cyclical. That means they will persist even after the economy has returned to full strength. So austerity measures—spending cuts or higher taxes—are required.

So the first two paragraphs of the quote would be the reasonable interpretation of the European situation at present. But the ideologues of the EU defy that logic.

How can they do that?

Simple, they have determined that:

… some of the bloc’s weakest economies are operating relatively close to full capacity … For example, the latest commission estimate is that the Spanish gap is just 4.6% of gross domestic product, despite nearly 27% of Spain’s labor force being officially unemployed … The commission believes that the “natural” rate of unemployment — if the Spanish economy were operating at full potential — is 23%.

That is the NAIRU has spiralled and full employment for Spain is consistent with an unemployment rate of 23 per cent.

If you believe that then please E-mail me and I will arrange transfer of ownership to you of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, with the Sydney Opera House thrown in for good measure, all for the small fee of $A1000. What a deal! Get in fast!

The EC is now considering the veracity of their estimates and Spain is leading a group of nations to force a change in the estimates of the output gap and a reduction in the estimated NAIRU.

The WSJ say:

The new methodology proposed by Spain could halve its estimated structural deficit this year and cut it by two-thirds next year, according to the Spanish finance ministry. That could mean a significant reduction in the amount of austerity that the beleaguered Spanish public would have to endure.

The witchdoctors and shamans are alive in Brussels and we will follow this story.

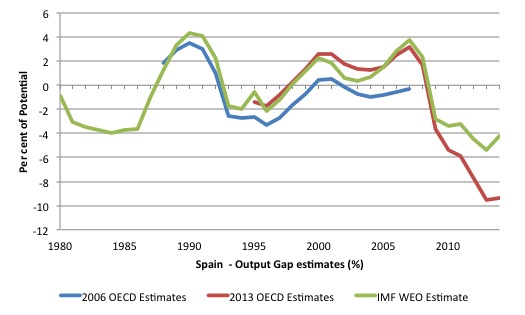

To demonstrate that point, the following graph compares the OECD output gap estimates for Spain published in their 2006 Economic Outlook to the most recent OECD estimates available (from HERE and the IMF World Economic Outlook estimates (as at April 2013).

The estimates for 2006 AND 2007 in blue are projections (data was published in 2006) while the 2013 and 2014 estinates in green and red are projections.

You can see that while the IMF and more recent OECD estimates coincide up to the crisis, they deviate quite sharply after 2009, reflecting the IMFs determination to under-estimate the extent of the crisis (as a means of selling its austerity policy line).

Comparing the two OECD series is interesting. The most recent estimates suggest that between 1998 and 2008 the OECD estimated that Spain was operating above is potential capacity whereas the earlier estimates suggested this occurred in only two of the years (2000 and 2001).

If the Spanish economy was really operating at such high-pressure we would expect an acceleration in the inflation rate. The next graph adds the annual inflation rate for Spain to the output gap series from 1995 and you can see that the inflation was low and stable throughout this supposed period of overheating.

That should provide a cautionary note when one is assessing the veracity of these output gap estimates.

But further, and relevant to the topic of today’s blog, note that, for example, in 2007, just before the crisis began the OECD was estimating that the output gap was 3.5 percent (which means actual output was estimated to be about the potential capacity of the economy), an assessment that the IMF supported.

If we match that to our understanding of the decomposition of the budget balance into cyclical and structural components then this implies that between those years 1998 and 2008, there was a negative cyclical component, given that the cyclical component measures the portion of the budget outcome that is the result of the economy being above or below full employment (that is, in conceptual terms, an output gap = zero).

Examining the OECD’s own estimates of the structural decomposition of the Spanish budget balance shows that Spain ran small deficits (as a % of GDP) from 1998 to 2004 and then small surpluses between 2005 and 2007, before the sudden and significant shift into deficit as the crisis unfolded.

But even in 2008, as the budget balance went from a 1.9 per cent surplus (2007) to a 4.5 per cent deficit (as a % of GDP), the OECD was still claiming the economy was operating above full capacity, given its estimate of the structural deficit was 5.7 per cent (that is, the cyclical component of the -4.5 per cent budget outcome was a positive 1.2 per cent.

Between the end of 2007 and the end of 2008, the Spanish national unemployment rate moved from 8.8 per cent to 14.9 per cent. What possible explanation could emerge to suggest that the economy was still producing above its potential.

The lack of internal consistency with all these estimates beggars belief.

But the problem really isn’t just that different methodologies or changes to samples or whatever else is involved produce different estimates. The problem isn’t just that the actual movements in unemployment and inflation bear no relation with the movememnt in estimated output gaps and that these estimates don’t align with the decompositions of the budget balances into cyclical and structural components.

The problem is that these estimates are used to guide and justify policy positions and when errors are made millions can lose their jobs – and it is never the economists who produce the error-prone estimates that join the jobless queues.

For example, in 2008, the policy implication of the OECD (and IMF) output gap measures was that the Spanish economy was overheating. The OECD’s budget decomposition data suggests that the sharp rise in the deficit in 2008 was all due to discretionary changes in Spanish government fiscal policy – which leads to accusations of laxity and profligacy.

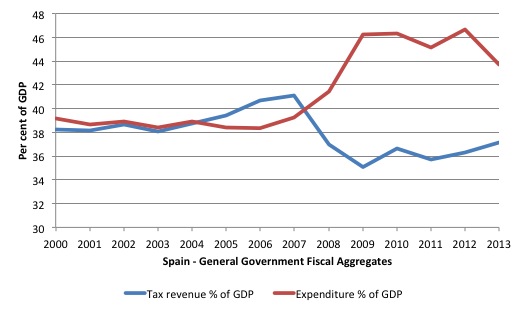

The next graph shows total general government revenue and expenditure for Spain between 2000 and 2012 (from IMF WEO, April 2013) as a per cent of GDP.

It depicts the classic fall into deep recession. Revenue plummets as economic activity declines sharply and income falls and government spending rises as the call on the welfare budget (at existing rates and programs) rises. Some of the increase in spending in the early days of the crisis was related to discretionary stimulus measures but a significant portion was related to the slump in real GDP growth.

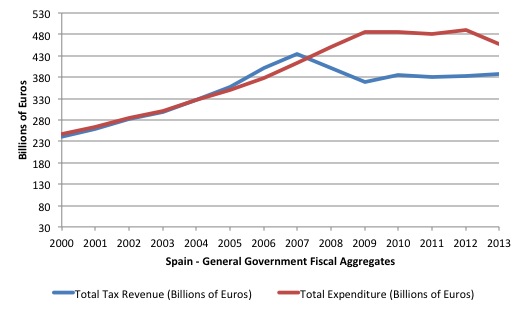

The following graph shows the same data in billions of Euro rather than expressing it as a share of GDP. The austerity set in in 2009 and beyond.

But the point is that if the economy was really operating above full capacity in 2008, then tax revenue would not have collapsed in the way it did.

It is obvious from any reasonable standpoint that the Spanish budget balance had a large cyclical component in 2008 despite the OECD (and IMF) estimates to the contrary.

Conclusion

My profession shines brightly in these sorts of situations – not!

The future generations will not look back on us very kindly. They will categorise my profession as confidence tricksters or worse. I wish I had taken up archeology or anthropology!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.