The Scottish referendum is still a victory for Scotland

Euro Crisis in the Press 2014-09-29

By Matthew Whiting

The Scottish referendum result strengthened Scottish nationalism and weakened Scotland’s position within the Union. That feels more like a victory than a defeat for Scottish independence.

Although David Cameron, and an apparently purring Queen, felt intense relief at the comfortable margin by which Scottish voters rejected independence, in reality the referendum looks more like a temporary delay in an ever closer journey to Scottish independence. Scottish nationalism, the driving force behind demands for independence, has come out even stronger from this process.

Winning majority support for a radical break with the Union was always going to be a tough task. The British constitutional tradition of preferring gradual reform and muddling through to all-out revolution meant that going straight to outright independence only 15  years after devolution was first introduced was not very likely. However, no-one could realistically consider the current outcome to be the final resting place of the constitutional changes that began in 1999.

years after devolution was first introduced was not very likely. However, no-one could realistically consider the current outcome to be the final resting place of the constitutional changes that began in 1999.

The recent referendum confirms the fact that it can no longer be assumed uncritically that Scotland’s rightful place is within the Union. This is highly significant because secession becomes much more feasible when there is no ideological hegemony amongst the political elite and the population as a whole that sees a territory as a natural or given part of a sovereign state. Take, for example, the position of Cornwall today – while there may be a dedicated few that are firmly committed to Cornish independence, the reality is that this is seen as somewhat laughable given that Cornwall is just ‘naturally’ a part of England and the United Kingdom. Scotland, in contrast, has lost the perception that its rightful place is sitting within the Union. This has been the case since the 1970s and even Margaret Thatcher acknowledged that Westminster would not stand in the way of Scottish demands for independence if that was the popular will of the people. The initial referendum on Scottish devolution in 1979 (which was passed but not implemented due to low turnout), the subsequent 1999 referendum on devolution, and the steadily increasing autonomy of Scotland since then, have all been a political recognition of the changing view that Scotland is, and ought to be, naturally a part of the United Kingdom. The results of last week’s referendum reinforced this even more starkly – they clearly showed that Scotland’s position in the Union is not naturally given, but is entirely contingent. Although the final result of 55% to 45% was more resounding than the polls predicted, a swing of just 200,000 votes would most likely have led to the resignation of David Cameron rather than Alex Salmond.

The ‘No’ vote was a reflection of the fear of the risks of independence – and these were very real risks that the SNP government grossly downplayed. But the ‘No’ vote was certainly not the defeat of Scottish nationalism. The desire for the referendum was never driven by lower Scottish economic outcomes than the rest of the UK or by Scotland having more left-leaning political preferences. In fact, per capita, Scotland is the third richest region in the UK (excluding revenue from North Sea oil) and its political preferences when it comes to taxing and spending are practically identical with those of every other region in the UK bar London and the Southeast, which skew the median voter to the right. If we just looked at economics and political preferences, Newcastle would have just as strong a case for a referendum as Scotland. Economic arguments ultimately defeated the case for Scottish independence, but economic arguments were not the driving force behind the desire for independence.

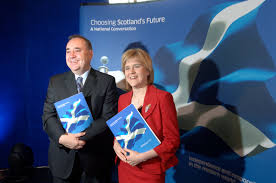

Rather what drove the rise in support for Scottish independence is nationalism, cleverly exploited by Salmond as leader of the SNP and linked to a populist anti-Westminster left-leaning platform. Of course, national identities are fluid, multiple and overlapping, but the Scots are more likely to identify with being ‘Scottish’ or ‘Scottish and British’ than ‘British’. Although it is not a given that voting for the SNP means that a person supports Scottish independence, just as people who do not vote for the SNP may still support independence as the Scottish Greens pointed out, nonetheless a strong sense of Scottish nationalism and supporting the SNP were the best predictors of being a ‘Yes’ voter.

The nature of the original Act of Union of 1707 maintained a separate Scottish identity (contrast this with the annexation and assimilation of Wales) and entering the Union from the Scottish perspective was based on the functional gains it offered (at the time, economic). The trouble with such motivation is that if these functional gains are no longer seen as sufficient, then the motivation to remain in a Union is undone. This, indeed, was the crux of the referendum contest where Salmond pitched the notion of self-determining Scots who could be more prosperous and democratic outside the Union against Alistair Darling’s warnings over currency, national defence and international affairs. At no point was an overriding Scottish nationalism challenged as being less preferable than an overarching British nationalism. Instead, Scottish consent to remain was secured by further recognising their distinct identity and granting them even more autonomy on this basis. This inevitably will lead to a radical restructuring of the rest of the United Kingdom and potentially extensive constitutional reform, further eroding the sense of a common British identity and an overarching Union.

The SNP and Salmond may have lost the election, but it bolstered the sense of Scottish nationalism; it gained more concessions from Westminster for a distinct Scottish identity; and within one week of losing the referendum the party gained 20,000 new members making it the third biggest party in the UK. That looks a lot more like a victory than a defeat.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Euro Crisis in the Press blog, nor of the London School of Economics

__________________________________________________________________

Matthew Whiting is Lecturer in British and Comparative Politics at the University of Kent.

Related articles on LSE Euro Crisis in the Press:

A Cosmopolitan Take on the Referendum

Foreign Reactions to the referendum in Scotland

Is an independence referendum the appropriate political tool to address the Catalan problem?