Issue communitarisation in Belgian politics: explaining the prolonged appeal of New Flemish Alliance’s nationalism

Euro Crisis in the Press 2019-10-30

By Koen Abts, Emmanuel Dalle Mulle and Rudi Laermans.

Since the early 2000s, the stateless nationalist party New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) has experienced a burgeoning growth without major changes in grassroots support for independence and only ambiguous ones for more regional autonomy. Issue communitarisation can help understand why.

When it came into existence in October 2001 nobody could predict that New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie) would become, in less than 10 years, the biggest party in Belgium. Yet, since the 2010 general election N-VA has dominated Flemish politics and scored consistently better than any other party in the country. Strangely enough for a party that declares the independence of Flanders as its ultimate goal, this has happened without major changes in grassroots support for independence and only ambiguous ones with regard to demands for more regional autonomy. A strategy of issue diversification, whereby the party expands its policy portfolio beyond the centre-periphery cleavage, can explain how the party managed to broaden its appeal beyond the limited circle of committed hard-core nationalists. As a matter of fact, apart from stealing votes from the Flemish nationalist and radical right Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang), the party attracted former voters of the Christian-Democratic CD&V and of the liberal Open Vld.

Yet, comparative studies on issue diversification rarely inquire into how such an expansion occurs in practice. When looking at N-VA’s discourse more in detail one quickly realises that the party has not only expanded into other policy areas, but it has also adopted a discursive strategy that consists in casting the centre-periphery frame over other cleavages, using it as a prism to interpret redistribution, power and identity conflicts explicitly in (sub-state) nationalist terms. We call this strategy ‘issue communitarisation’, or the systematic construction within the fields of economy, politics and culture of an unresolvable antagonism between the Flemish and the Walloon/francophone community. As a consequence, in N-VA’s discourse, nationalism acts as an overarching frame that subsumes other ideological frameworks often attributed to the party, notably neoliberalism, populism, conservatism and (we add) welfare producerism.

How has the party done that?

Political Potential: Responsible Governance and the Logic of Two Democracies

In the realm of politics, N-VA portrays Belgium as the sum of two democracies (Flanders and Wallonia) that are constantly at loggerheads on all subject matters. Such flawed political system inevitably ends up in a form of overall ‘blocked democracy’, since majority rule (which would favour the Flemings) has been replaced by a mandatory consensus system favouring the francophone minority. In this way, the Flemings are described as a minoritised majority and Belgium as an inevitably divided country. According to this ‘two democracies’ argument, Belgium is not a democracy because there are two languages, two cultures, two media systems and two public opinions that cannot be reconciled with each other: ‘the separation of the souls has been there for long time, people only do not dare extend it to the facts’.

Economic Potential: Individual Responsibility and Welfare Producerism

In the field of the economy, N-VA has clearly adopted a neoliberal position favouring limited state intervention, austerity, a more flexible labour market and lower taxation. Yet, the party views on the economy are also strongly influenced by its nationalist ideology and can be better defined as a form of culturalised welfare producerism. By welfare producerism we mean a conditional conception of solidarity based on the deservingness criteria of control, attitude and reciprocity. According to such a conception, welfare recipients are seen as less deserving if they are considered as being responsible for their state of need (control) and/or if they are perceived as not making enough of an effort to get out of poverty (attitude). Furthermore, people who have contributed more to the system should receive more once in need (reciprocity). N-VA communitarises welfare producerism because, in the party’s discourse, the hard-working Fleming nation is pitted against the lazy Walloon one, which lives off Flanders’ economic performance. In this connection, several times, N-VA has described Flanders as a milk cow forced to pay opaque subsidies to Wallonia, which the party has also qualified as ‘a permanent blood transfusion to a patient who parasites on his donor while squeezing his arteries’. Belgium therefore becomes a hindrance to the full blossoming of the true potential of Flanders. Furthermore, as the Flemish nation is represented as being made up of hard workers, austerity is described as a tool to revert resources back from the recipients (Wallonia) to the contributors (Flanders). In such a framework, solidarity (for the Flemings) and efficiency are seen as being compatible.

Cultural Potential: Closely-Knit Community and Deserved Citizenship

The party has also expanded in the realm of culture and immigration providing a very clear profile that is sceptical of multiculturalism and requires a strong assimilationist effort from newcomers, while at the same time officially subscribing to civic forms of identity and taking distance from the more ethnic-based project of Flemish Interest. Here again, however, N-VA has played the communitarisation card by arguing that Flanders and Wallonia have totally opposite positions on immigration: the former more grounded in ‘integration’ (inburgering); the latter embracing a laxer approach. As the party has clearly declared in 2008 with regard with the so-called snel-Belg wet (which facilitated the procedure for acquiring Belgian citizenship), ‘also in these matters, the communitarian conflict is deep-seated. (…) Whereas Flanders offers chances to newcomers, but also formulates requirements, the federal level gives the Belgian nationality generously away without any demands’. The consequence, as they stated in their 2009 manifesto, is that (francophone) Belgium is supposed to prevent Flanders from following ‘a good welcome policy that makes cultural and socio-economic integration possible’.

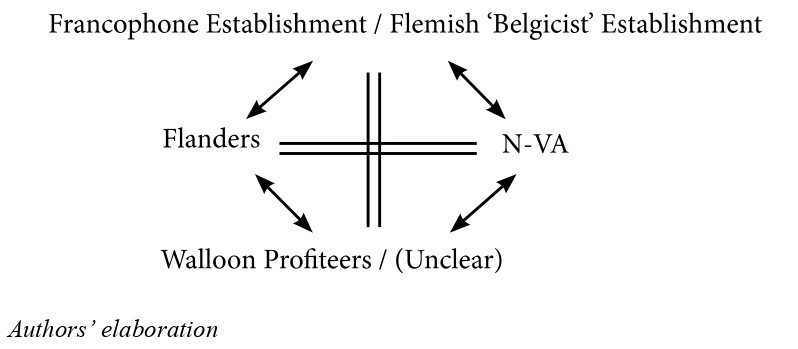

N-VA’s Socio-Political Space: Homological and Antagonistic Relations

Through its strategy of issue communitarisation, N-VA portrays the Flemish nation as consistently thwarted in its efforts to develop its full potential. Flanders cannot achieve good governance and exercise its legitimate democratic power, take complete advantage of its economic prosperity, welfare and culture of industriousness, and stick to its own values and manage cultural diversity in a way conducive to the preservation of a ‘closely-knit community’. In this way, N-VA has constructed the Belgian political space as an opposition between two homological relationships: that between Flanders and N-VA (as the embodiment of the Flemish general will) and that between a superordinate and a subordinate Other (see Figure). These two Others change depending on context, but, at the Belgian federal level, they usually coincide with the francophone political elite and the ‘lazy Walloons’ respectively. At the regional Flemish level, on the contrary, the superordinate Other is represented by the Flemish ‘Belgicist’ political parties, while the subordinate Other is less clearly defined, an ambiguity probably due to the fact that identifying a clear Other from below at the Flemish level might have electorally counterproductive effects. What is interesting in a comparative perspective is that the specification of the Others at the federal level are much clearer than at the regional one. Hence, N-VA’s structuring of the Flemish political space is over-determined by its nationalist rhetoric.

Figure: N-VA’s discursive diamond in the federal and regional arena

The discursive strategy of issue communitarisation contributes to understanding how stateless nationalist and regionalist parties can diversify their policy portfolio, while at the same time keeping the support of committed hard-core nationalists. Instead of simply going beyond centre-periphery, N-VA has ‘exported’ the centre-periphery frame to other ideological conflicts, thus addressing the paradox, suggested by Sonia Alonso, whereby ‘the more the party wins at the centre the more it loses at the extreme’. Also, in a wider theoretical perspective, N-VA’s issue communitarisation suggests that nationalism acts as a shell that hosts other ideologies (neoliberalism, populism, conservatism etc.) rather than being subsumed by them as previously proposed by Michael Freeden. This is because nationalism focuses on the determination of the relevant sovereign community and its political legitimacy, which is logically prior to the application of principles making up other ideologies that provide ‘plans of actions for public political institutions’. As a result, nationalist discourse can embed more complex ideologies in a particular social and territorial context, contribute to the determination of a collective interest, endow the political and economic spheres with a particular moral and emotional nature, and define the boundaries of solidarity.

For a longer discussion of this topic, see the authors’ recent article in West European Politics.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Euro Crisis in the Press blog nor of the London School of Economics.

Koen Abts is assistant professor at Tilburg University and research fellow at the Institute of Social and Political Opinion Research at the University of Leuven.

Emmanuel Dalle Mulle is post-doctoral researcher at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, and non-resident fellow at the Centre for Sociological Research of the University of Leuven.

Rudi Laermans is professor of social theory at the University of Leuven.