The Weaponization of Laïcité Against Muslims: Pushing More Towards Extremism

Euro Crisis in the Press 2021-06-16

By Tanzila Jamal

In the last decade, France has seen particularly devastating terrorist attacks with incidents such as the Nice truck attack in 2016 sustaining a death count of nearly 84 people, the series of stabbings at the Notre Dame basilica, or more recently the fatal stabbing of a policewoman in Southern France. With a rise in terrorist attacks, a fervent demand from the public for protection and French policymakers has answered with several policies targeting what they assume to be the primary cause. Policies have included a ban on niqabs (full-face covering) and a ban on burkinis, among others. More recently came a proposal for a series of policies that would aim to target radicalism. These policies are not seen as an infringement on religious freedom through the French concept of “Laïcité”, a principle created in 1905 to promote a more secular France. This article will explicate laïcité and its recent weaponization in marginalizing the French Muslim community, thus pushing more to extremism.

In the last decade, France has seen particularly devastating terrorist attacks with incidents such as the Nice truck attack in 2016 sustaining a death count of nearly 84 people, the series of stabbings at the Notre Dame basilica, or more recently the fatal stabbing of a policewoman in Southern France. With a rise in terrorist attacks, a fervent demand from the public for protection and French policymakers has answered with several policies targeting what they assume to be the primary cause. Policies have included a ban on niqabs (full-face covering) and a ban on burkinis, among others. More recently came a proposal for a series of policies that would aim to target radicalism. These policies are not seen as an infringement on religious freedom through the French concept of “Laïcité”, a principle created in 1905 to promote a more secular France. This article will explicate laïcité and its recent weaponization in marginalizing the French Muslim community, thus pushing more to extremism.

What is Laïcité and what are its origins?

Laïcité roughly translates to “secularism” and was enacted by The Law of 1905, officially segregating the Church from the government. Per separating the Church and State, the French concept of secularism also promised to guarantee “the freedom to practice religion.” The principle of laïcité is not fundamentally anti-religion but rather a principle emphasizing the freedom of conscience and religion. According to the official French Minister of Foreign Affairs Office, as France becomes more culturally diverse, secularism is needed more than ever to ensure the people can live together peacefully, enjoying the “freedom of conscience.” With the emergence of terrorist attacks in France, the role of laïcité has often been used in conjunction with the French Muslim community though the principle applies to all religions.

Since 2004, French politicians have attempted to use policy to forge a version of Islam they believe would be more compatible with French ideals and values. This has led to the weaponization of laïcité, mutating the principle from a guarantee of religious freedoms and freedom of conscience to a tool in restricting religious freedoms, particularly for the Muslim community. In 2003, people began to question if wearing headscarves (hijabs) by schoolgirls was compatible with French principles, as schools were considered a neutral, religion-free zone. In consideration of these concerns, the government hired the Stasi Commission to review the issue. The report concluded that religious signs in public constitute “a threat to public order,” with the French parliament proceeding to ban the wearing of religious symbols in public schools based on laïcité. Though the law affects all religious gear including Sikh turbans, Jewish kippas, and large Christian crosses, it was primarily aimed at schoolgirls wearing hijabs. This prohibition was followed by cases of Muslim schoolgirls being expelled or removed from classes if the school administration deemed any clothing items ostentatious. Most notably was the case of a 15-year-old Muslim schoolgirl being removed from class for wearing a long black skirt as administrators saw it as a religious symbol. This has not been an isolated incident, with over 130 cases of high school and college girls being banned from classes due to “ostentatious” outfits. The devolution of laïcité has resulted in legal islamophobia, promoting discrimination against French Muslims as acceptable under the guise of secularism.

The Emergence of Islamophobic Sentiment

While the recent phenomenon of terrorist attacks and a post 9/11 “war on terror” has been attributed to the negative perception of Muslims, this negative image is not a recent emergence in France. Anti-Muslim sentiments in France can be traced back to France’s historical role as a colonizer of Arabic and Muslim people. At the peak of its life as an empire, the French empire colonized many North African countries, including Tunisia, Algeria, Lebanon, Syria, and Morocco. During France’s time as a colonizer in Algeria, African Muslims were often deprived of their identity, with colonial authorities disestablishing Arab-speaking schools. Colonial life was heavily controlled, and ‘‘Code l’indigénat’’ (native code) was used to “strip native inhabitants of all civil rights, and of their status as complete human beings.” The disbandment of French colonial rule over these territories resulted in an influx of North African immigrants to France, with the French government also enlisting low-skilled workers from these countries.

An influx of North African immigrants materialized “banlieues” (slums), plagued with rampant crime, poverty, and unemployment. More than 4.4 million people of Arab or African heritage live in banlieues where they and Jews face extreme discrimination. From the beginning, Muslims and those of African and Arab heritage have been placed on the fringes of French society by the government and natives.

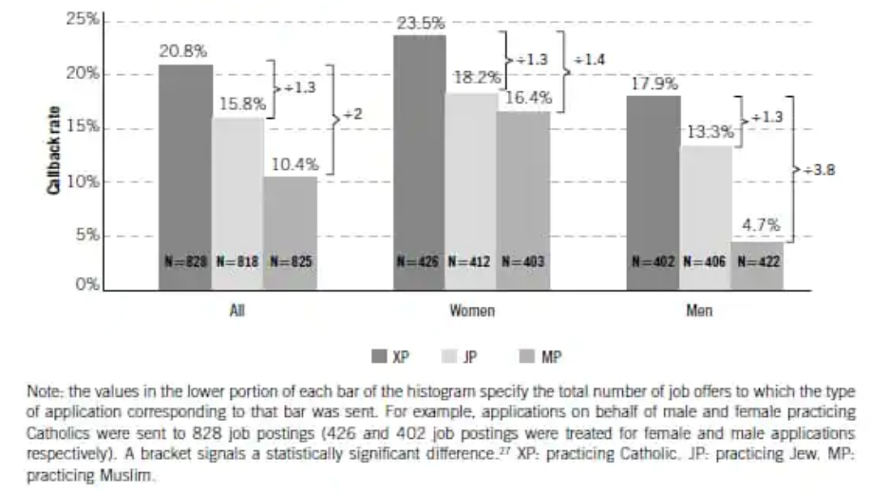

This trend of discrimination has bled into other facets of life, with French Muslims experiencing extremely high levels of unemployment. In 2010, Marie-Anne Valfort from the Institute Montaigne conducted a study to compare the experiences of French Christians and French Muslims. Marie-Ann Valfort is an Associate Professor at University Paris I Panthéon Sorbonne and has written several research papers focusing on anti-Muslim discrimination. The report concludes with Valfort determining that Muslims experience staggeringly high amounts of discrimination when job searching, as Figure 1 shows how only 5% of Muslim men are likely to be called back.

Figure 1: Callback rates for practicing Catholics, Jews, and Muslims, unseparated by gender and broken down by gender.

The study continued to show how this discrimination continued to carry over when applicants indicated they were secular, though slightly less (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Impact for Muslim men of appearing as secular rather than practicing, according to whether their profile was ordinary or outstanding.

In his journal, Engy Abdelkader analyses French perception of Muslims before and after terrorist events, focusing specifically on the incident with Charlie Hebdo. Abdelkader. Abdelkader is currently a political science professor at Rutgers University, where she explores religion and government using her extensive knowledge as a lawyer. In 2014, 40% of French survey respondents found Islam to be a threat; however, in 2015 after the terrorist attacks, 76% of French survey respondents held optimistic views on Islam. She attributes this to social media platforms such as Twitter, where Muslims banded together publicly against the actions of the terrorist and in solidarity with the victims. She does, however, note that in 2016, 46% of French survey respondents claimed to fear that Muslim refugees would increase the chance of terrorist attacks.

Another factor in French islamophobia can be linked to the economic status of the country. Abdelkader notes that negative opinions regarding Muslims coincide with financial crises and an increase in Muslim immigrants. In 2008 when the French economy suffered due to the world financial crisis, French survey respondents vocalized the belief of Islam being incompatible with French values. Abdelkader ascribes this belief to the fear that immigrants were taking jobs though this is not true as shown previously in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

French Politicians and Islam

The rise in terrorist attacks has culminated in public demand for politicians to address the rising problem. Politicians have taken various methods to heed this demand, though regardless of party lines, there has been a general ambivalence towards the notion of Islam in France. Politicians such as current-standing President Emmanuel Macron have called for policies that would target radical Islam, emphasizing that he is not attacking the religion or practitioners but pushing for a French version of Islam. When introducing his plan to combat radical Islam, Macron commented that his goal was to “free Islam in France from foreign influences” and to create an “Islam des lumières” (Islam of Enlightenment). However, Macron is also the first President to acknowledge the obstacles facing French immigrant communities, particularly mentioning how “We have thus created districts where the promise of the Republic has no longer been kept, and therefore districts where the attraction of these messages, where these most radical forms were sources of hope.” His comments, however, have contrasted the policies proposed by his party in recent years. Despite his position as a member of the La République En Marche! Party (a centrist and liberal party), the President has been accused of pandering to the far right to gain votes in the upcoming election. Critics have condemned the recently proposed separatism policies as a ploy by Macron to gain voters against Marine Le Penn, his current rival.

Recently, higher education minister Frédérique Vidal has also called for a formal investigation to examine “Islamo-leftist” environments in universities. “Islamo-leftism” describes the belief that challenging racism, colonialism, and similar concepts are akin to promoting radical Islamism and racism. Vidal has faced severe backlash for this instigation, with academics and the CNRS (The French National Centre for Scientific Research) criticizing her for subscribing to the ideology which does “not correspond to any scientific reality.” The Minister has reasoned the need for an investigation by exclaiming that it is needed to “distinguish proper academic research from activism and opinion.”. President Macron’s office has not yet commented on Vidal’s decision, though in the past, Macron has commented that focusing on race and discrimination served only to create a divide within French society. Despite backlash from academics, several right-wing politicians have spoken out in support of the investigation, deeming it necessary.

Marine Le Penn, the current President of the National Rally party and runner-up for the French Presidency, has also commented on approaching Islamist radicals. Le Penn’s party, the National Rally, is a far-right political party mainly promoting anti-immigration and anti-globalist beliefs while advocating for nationalism and a secure France. Le Penn previously lost the Presidential candidacy to Emmanuel Macron in 2017 and is now campaigning once more. In a recent move to increase her voters, Le Penn proposed a ban on hijabs in all public spaces, a move that resulted in her being tied in votes with Macron. Le Penn has also gone further to blame immigration and lax government policies for allowing Islamism and terrorism to rise. She has commented, “Acquiring French citizenship should be made harder and contingent on respecting French “customs” and “codes.””. In a more recent debate against Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin, Le Penn criticized the government for not being strict enough in handling radical Islam and “limiting everyone’s freedom to try to modify the freedoms of a few Islamists”. Interior Minister Darmanin attacked Le Penn’s advocacy for a hijab ban, arguing that “It’s citizens’ freedom to be able to live their faith freely in the public space”, “There won’t be a clothing police”, and that in response to women that are being forced to wear hijabs “it’s better to fight the men who are creating the community pressure”.

Repercussions of Anti-Muslim Policies

The introduction of anti-Islamic policies is a reoccurring trend. Most recently, Prime Minister Emmanuel Macron introduced a series of separatism policies which would include banning hijabs for minors under 18, banning homeschooling for Muslims, and the ability to close mosques or associated organizations if under suspicion and other provisions. Though the French lower house National Assembly has voted in favor of the bill, it has not come to fruition yet as it awaits the Senate’s vote. Macron claims the bill aims to reforge Islam to create a new version that would more closely align with French ideals, highlighting the secular nature of the country. Critics have spoken out against these policies, arguing they stigmatize Muslims as terrorists and infringe upon the freedom and rights of French Muslims. Amnesty International’s researcher Marco Perolini has also commented how “French authorities use the vague and ill-defined concept of ‘radicalization’ or ‘radical Islam’” to justify the imposition of measures without valid grounds, which risks leading to discrimination in its application against Muslims and other minority groups”.

These policies have come to a rise in Islamophobic sentiments and hate crimes being committed against French Muslims. In 2014, there were a reported 133 hate crimes against Muslims while there were more than 400 incidents in 2015, as reported by the French National Human Rights Commission (CNCDH), meaning a 223% increase. Abdallah Zekri, the head of the National Observatory of Islamophobia, announced a 53% jump in hate crimes from 2019 to 2020. Overall, hate crimes and Islamophobic sentiments have risen greatly in the last few years, with policies legitimizing this fear.

Though these policies have aimed to reduce radicalism, an unintentional consequence of targeting innocent French Muslims is the further marginalization of a minority group already on the fringes of society. The refusal to let French Muslims practice and express their religion freely contradicts their identities, contributing to the growing disconnect from French society many Muslims already feel. Segregating French Muslims, particularly young ones (through the hijab ban, for example), can create more vulnerability and play a massively contributing push factor to radicalization.

Conclusion

Conclusively, it is evident that politicians have weaponized the French concept of laïcité to foster a hostile environment towards French Muslims. The word, originally used to dictate freedom of religion and freedom of conscience, is now utilized to exploit the fear of the people and vilify the French Muslim minority. Policies created under this guise aim to further stereotype all Muslims as terrorists and further isolating an already marginalized minority. While many have pointed at terrorist events as justification for these policies, it is evident that Islamophobic sentiment has been prevalent in France since long before. The country’s past as a colonizer of Muslim Arabs and North Africans has played a heavy hand in these new separatism bills. Muslims in France are already heavily discriminated against, with many resigned to live in banlieue with low chances of employment; Muslim youth are also being discriminated against, with their ability to express their religious identity tarnished. Ultimately, the legitimization of islamophobia through the weaponization of laïcité policy has resulted in a drastic increase of hate crimes and will further alienate vulnerable people and push them towards radicalism rather than away.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Euro Crisis in the Press blog nor of the London School of Economics.