Vox, Covid-19, and populist discourses in Spain

Euro Crisis in the Press 2021-06-29

By José Javier Olivas Osuna and José Rama

The radical right party Vox has been a harsh critic of the Spanish government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on the qualitative and quantitative content analysis of parliamentary speeches, during the first wave of the crisis we find that Abascal’s interventions became increasingly populist as the pandemic progressed and that there is also evidence of a ‘spillover’ or contagion effect, with the level of populism displayed by other parties also increasing. This post summarises some of the most important findings of the research we recently published in Frontiers in Political Science.

The analysis of populist discourses during great events, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, can help us to understand how populist leaders adapt their communicative style to take advantage of changing circumstances. Populist movements often appear within a crisis context. This was the case of some populist leaders in Latin America that emerged after the hyperinflationary crisis in the late 1980s, or the recent emergence of radical populist movements in Europe such as the Alternative for Germany, Brothers of Italy, and Vox after the Great Recession.

Populism finds in economic, social and political crisis a window of opportunity because crisis erodes trust in representative institutions, fuels grievances, and serves as justification for radical measures. Moreover, populists frequently cite social, political and economic problems – as well as the failure to address them – to propagate a sense of crisis and turn ‘the people’ against a dangerous ‘other’. Unfortunately, the simplistic solutions and blame attributions of populist leaders often trigger similarly simplistic and confrontational responses from their political adversaries. These populist performances can become contagious and may further divide society and polarise the electorate.

Populism in Spain during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic

In Spain, the Covid-19 crisis has induced greater demands for techno-authoritarian decision-making, strong leadership, willingness to give up individual freedom, and support for the idea of recentralisation of devolved powers. All these ideas resonate with the discourse of Vox, which is also the party that Spaniards with anti-democratic views are more prone to support. Vox has also grown significantly and become the third largest party in Spain and it is, therefore, a party worth studying in the context of this health crisis.

One way to study populist discourses is to compare the density of populist features for each of the core dimensions of populism, namely: antagonism, morality, the idealisation of society, popular sovereignty and personalistic leadership. Table 1 below provides a definition for each of these dimensions.

Table 1: The core dimensions of populism

Populist featuresAnti-populist featuresDepiction of the polityDual and antagonistic description of polity: ‘us’ vs ‘them’, ‘the people’ vs ‘the elite’ or ‘the other’ (migrants, minorities, intellectuals, etc.).Rejection of political, legal and/or economic establishment. Claims for radical change. Confrontational tone, militaristic terms.

Complex and nuanced (non-antagonistic) depiction of the polity. Endorsement or approval of political, legal and economic establishment. Claims for gradual change.References to working together with political opponents and reaching agreements.

MoralityMoral interpretation of actors. Moral distinction and hierarchy (superiority and inferiority). Claims against the legitimacy of the other actors. Victimisation/blame discourses.Ad-hominem critiques and negative emotions. References to ill-intentioned, unfair or immoral behaviour or political opponents.

Political actors are not classified according to their moral standing. The legitimacy of political opponents and their ideas is acknowledged.Critiques not focused on the proponent’s personal attributes or motives but on their actions or policy proposals (usually backed on empirical evidence).

Construction of societyIdealisation of society. Anti-pluralist depiction of ‘the people’ focused on identity, nationhood and/or ahistorical ‘heartland’. References to unity and singularity, hyperbolic descriptions.Emphasis on difference with ‘the other’ and in-group homogeneity. Exclusionary claims. Emotional language.

Complex and nuanced depiction of society and history. Pluralist portrayal of the people. References to diversity of views and interests. Utilisation of empirical data to back claims.Emphasis on commonalities with ‘the other’ and in-group heterogeneity. Recognition of a common space. Inclusive claims

SovereigntyAbsence of limits to popular sovereignty. Majoritarian logic. The ‘will of the people’ is expected to prevail over laws, minority rights and institutions.Preference for direct democracy tools. Praise of referendums, public consultations and mass mobilisations.

Popular sovereignty limited by laws and formal rights. Emphasis on representative democratic tools. Complexity in decision-making is acknowledged.References the protection of minority rights and interests and to institutional and legal checks on the will of the majority.

LeadershipLeaders voice ‘the will of the people’ and represent their interests. Non-mediated relation with the people. Leaders are described as more important than political parties.Focus on the actions, decisions and ideas of leaders. Idealisation of their achievements. Charisma takes precedence over expertise.

Leaders’ relations with people is mediated by institutions. Political parties represent people’s interests. Parties and other institutions are expected to control and be heard by political leaders.Focus on the actions, decisions and ideas of political parties and institutions, not simply those of individuals.

Source: Olivas Osuna (2020)

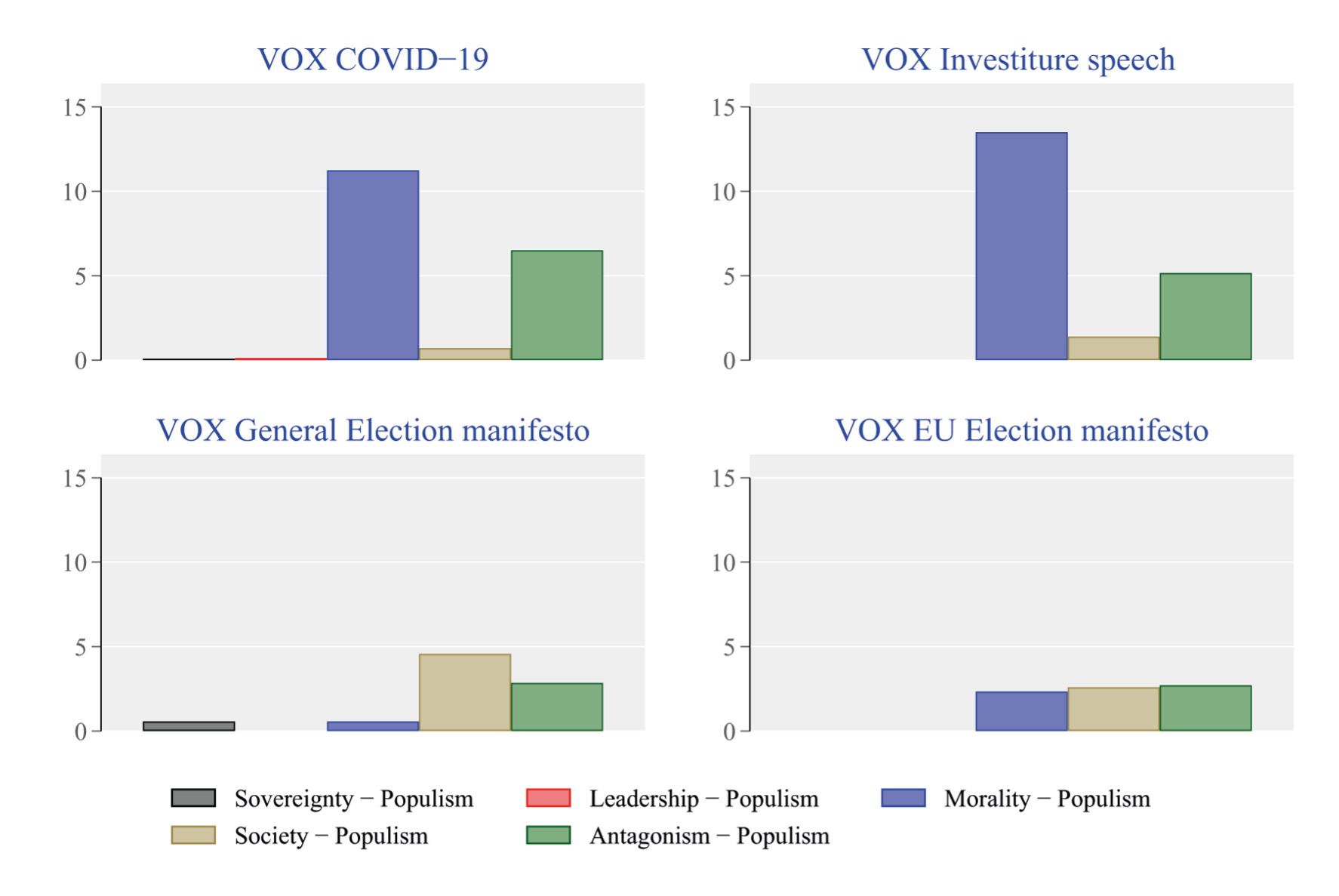

We have analysed the transcripts of the populist discourse of Vox during the debates for the approval and extension of the ‘state of alarm’ to fight against Covid-19. Our analysis reveals that, in comparison with Vox’s political manifestos, the idealised depiction of society lost relevance during these debates, whereas the moral and antagonistic dimensions largely increased their salience. Figure 1 shows the density of each of the populist features in these statements and in the party’s manifestos.

Figure 1: Aggregate levels of populism in the discourse and party manifestos of Vox

Note: Density is measured as the number of references to each feature per 1,000 words.

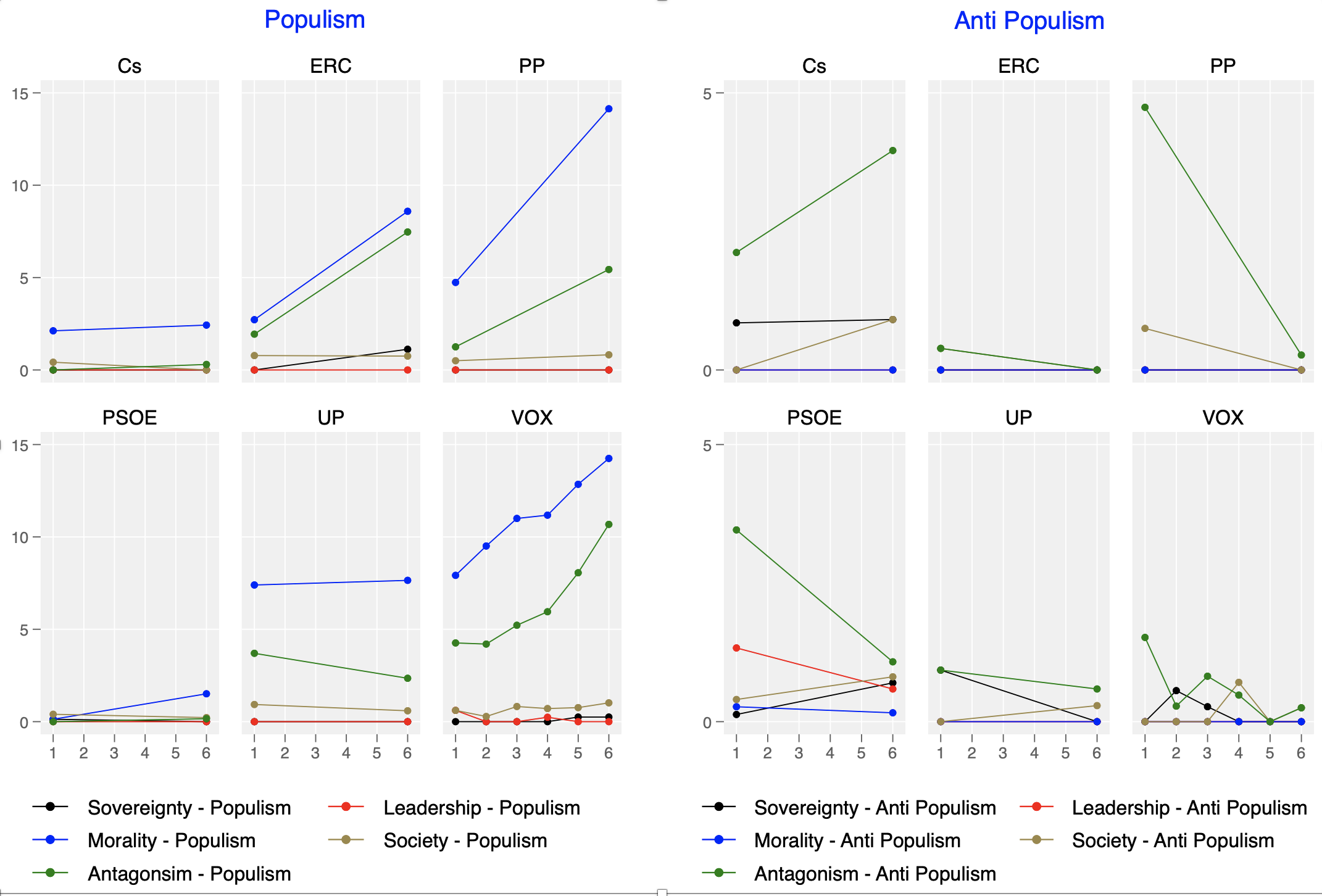

Figure 2 shows that from 25 March to 3 June, the density of morality and antagonism references steadily increased during the different interventions in the case of Vox, and that ‘anti-populist’ allusions – i.e., referring to a pluralist or liberal conception of democracy – were extremely rare and decreasing in the speeches of Abascal.

Figure 2: Evolution of populist and anti-populist statements by major Spanish political parties (25 March – 3 June 2020)

Note: The figure shows how the frequency of populist and anti-populist statements by political parties changed from 25 March (1) to 3 June (6).

It is worth noting that Abascal’s speeches paid very little attention to the specific aspects of the pandemic. They largely attempted to delegitimise the Spanish government and its allies by accusing them of disinformation and of having hidden motives, such as eroding the unity of Spain and trying to establish a communist authoritarian regime. While the number of populist references increased, the tone of his statements also became more hyperbolic and aggressive.

‘Mr Sánchez, you can’t disguise this: tens of thousands of dead Spaniards due to sectarianism and criminal negligence by this government and millions of Spaniards ruined …’

‘I believe that Mr Iglesias wishes a civil war, […], I believe that his vanity and fanatism is capable of provoking a tragedy in Spain, but we are not going to fall into his provocations.’

(Santiago Abascal, 3 June 2020)

Our analysis also provides evidence of spillover effects in other parties’ communications. Pablo Casado, the leader of the People’s Party (PP), drastically modified his discourse between the first and last Covid-19 debate. Anti-populist features were abandoned and replaced by abundant populist antagonism and morality features. Although the style of Casado was not as emotional and aggressive as that of Abascal, the density of populist references displayed was also very high and several of the critiques were similar to those made by the leader of Vox.

Meanwhile, the speakers of Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) and Unidas Podemos (UP), parties that are usually classified as populist, took advantage of the excessive claims by Abascal to caricature and demonise Vox as well as the other right-leaning parties, the PP and Ciudadanos (Cs). Only the speakers of Cs and Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, the leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), maintained a discourse with fewer populist than anti-populist references.

Explaining the propagation of populist rhetoric

The Covid-19 pandemic was seized upon by Vox as an opportunity to fuel discontent and transform the health and economic crisis into a political crisis in which they could set the agenda and present themselves as the only strong opposition to the government.

Abascal and other leading figures in the party employed an aggressive performative style, distancing themselves from what is politically correct and emulating the ‘bad manners’ of former US President Donald Trump and other prominent populist figures. Other parties reacted to these performances by also engaging in blame attribution and moral condemnation. Two different mechanisms seem to explain the propagation of populist discourses.

First, by adopting hyperbolic and confrontational rhetoric, populist parties can gain more media attention and differentiate themselves from other political forces. This is a sort of ‘populist outbidding’ process. Other political parties on the same side of the left-right spectrum, such as the PP in this case, may choose to adopt a similar form of populist rhetoric to avoid losing voters to more radical parties, such as Vox.

The recent regional elections in Catalonia in February this year and Madrid in May help to illustrate this effect. In the former election, the PP adopted a moderate stance, but was largely beaten by Vox, while in the latter, the PP leader Isabel Díaz Ayuso used a Manichean, confrontational communication strategy and managed to largely outperform Vox – which obtained 9.1% of the vote as opposed to 18.5% in the November 2019 general election. This underlines that maintaining a pluralist discourse in the context of crisis and polarisation can be electorally damaging in the short-term.

Second, parties from the other side of the political spectrum may also enter into a populist confrontation dynamic with the party responsible for the initial escalation. Once a leader breaks implicit conventions on what is acceptable to say in parliament, other leaders may follow and thereby help normalise populist articulation, strengthening the sense of crisis.

Party speakers in Spain engaged in aggressive attacks on each other with hyperbolic accusations such as suggesting that some parties were ‘euthanising’ part of the population, calling for a military coup d’état, wishing a civil war, or engaging in fascism. This crossing of dialectic red lines in parliament was later visible in a more aggressive tone and further polarisation in the public sphere, thus contributing to increased tensions and divisions in society.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at Frontiers in Political Science

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of LSE Eurocrisis or the London School of Economics. This blog has been also posted on EUROPP (European Politics and Policy) Blog

—

José Javier Olivas Osuna is Senior Talento Fellow at the National Distance Education University (UNED), Madrid and Research Associate at LSE IDEAS.

José Rama is a Lecturer of Political Science in the Department of Political Sciences and International Relations, Faculty of Law, Autonomous University of Madrid. He is Guest Lecturer in the Department of European and International Studies, King’s College London.