Online discussions show the depth of Eurosceptic feeling across Europe, but they tell us very little about the kind of EU that citizens would like to see

Euro Crisis in the Press 2014-03-07

European Parliament elections are not technically about the question of ‘more or less Europe’ because the European Parliament does not have a major say over questions of membership or Treaty revision. However, we find lively online discussions about such constitutional issues over the EU polity during the election campaign. The most frequently visited online news platforms throughout Europe provide a large number of stories on European integration and their readers take the opportunity to leave comments about their opinion of the EU. The vast majority of online discussion contributions criticise the EU in one way or another and complain that the EU is undemocratic. Yet, since no proposals for reforming the union are provided, such ‘diffuse Euroscepticism’ provides a major challenge to the legitimacy of European integration.

Together with my co-authors Asimina Michailidou and Hans-Jörg Trenz, my recently published study on online debates during the European Parliament elections in 12 EU countries assesses this state of affairs. News websites increasingly include interactive features, known as Web 2.0, where readers are able to post comments in response to articles and other readers’ comments. Significant numbers of citizens use this opportunity to comment, and a much larger number follow these discussions passively. To complement knowledge on the opinion of party politicians and electoral campaigns, such user comments contesting the EU polity in direct unsolicited relation to campaign news stories shed light on evaluations of the European Union.

Assessing online comments about the European Union

To assess online communications, we first use a typology of evaluations of the EU. This incorporates three different dimensions: views on the principle of integration, views on further integration, and views on the EU’s current institutions. Depending on whether evaluations on each of these dimensions are positive or negative, a typology of six different types of evaluation of the EU can be outlined. This ranges from explicitly pro-European (Affirmative European) views at one end of the scale, to anti-European views at the other. The Table below shows these six categories and the note explains briefly what each type of EU evaluation consists of.

Table: Typology of evaluations of the EU

Note: The Table shows the six ‘types’ of EU evaluation based on whether statements are positive or negative concerning the principle of integration, the EU’s institutional set-up, and the integration project (i.e. further integration). The six evaluations are: Affirmative European (positive evaluation of all three dimensions); Status quo (a statement that supports integration in principle and the EU’s current institutional set-up, but not further integration); Alter-European (an evaluation that supports future integration, but disapproves of the EU’s current institutions); Eurocritical (supports principle of integration, but neither the EU’s current institutions nor future integration); Pragmatic (does not support integration, but accepts the EU’s current institutions); and Anti-European (does not support any integration or the EU’s institutions). Source: De Wilde and Trenz

In the case of online communications, however, the majority of contributions criticise some aspect of the EU in terms of competences, membership and institutions without reflecting on the principle of integration or possible future trajectories. We call this ‘diffuse Euroscepticism’, in the sense that it criticises the EU without making any specific statement about how it should be changed, or proposing any specific future reform. Yet, very few of these diffuse Eurosceptic opinions advocate a complete dissolution of the EU or even that their own country should give up membership. In that sense, the existence of the EU and our membership of it are taken for granted across Europe.

Particularly striking is the fact that negative opinions outnumber positive ones in all EU member states. Thus, the traditional assumption that some member states are more Europhile while others are more Eurosceptic should be reconsidered, at least when it comes to public opinion as constructed in online debates. Chart 1 below shows the percentage of online communications in our study which fall under each of the six categories of EU evaluation and the diffuse Eurosceptic category: together with the justification diffuse Eurosceptic communications provide to support their opinion.

Chart 1: Evaluations of the EU in online discussions and justifications for ‘diffuse Euroscepticism’

Note: The pie chart on the left shows the percentage of online discussion contributions which belong to each of the six types of evaluation plus ‘diffuse Euroscepticism’. The bar on the right shows the proportion of the different justifications which diffuse Eurosceptic statements provide (those justified on the basis of democracy, culture, etc.).

Note: The pie chart on the left shows the percentage of online discussion contributions which belong to each of the six types of evaluation plus ‘diffuse Euroscepticism’. The bar on the right shows the proportion of the different justifications which diffuse Eurosceptic statements provide (those justified on the basis of democracy, culture, etc.).

As Chart 1 shows, citizens making diffuse Eurosceptic statements primarily do so because they find the EU undemocratic. They argue that their voices are not heard, that they cannot influence what is being decided in the EU and that unelected bureaucrats within EU institutions have too much power. So far, a remarkable consensus across EU member states is apparent. In their online arguments European citizens and politicians alike agree that they want a Europe, but not this Europe – because it is undemocratic.

Few offer templates for the kind of Europe they do want, and the ones that do rarely agree with each other. While some advocate less Europe because they do not like the current EU, others want more Europe for the same reason. Some see a solution in reverting back to the EU as a common market with a deletion of all the political integration and state-like symbolism. Others want to democratise Europe, for instance by directly electing the President of the European Commission or by making the Commission fully accountable to a majority in the European Parliament. The advocates of such changes accept that this democratisation will probably come with a transfer of even more power to EU institutions.

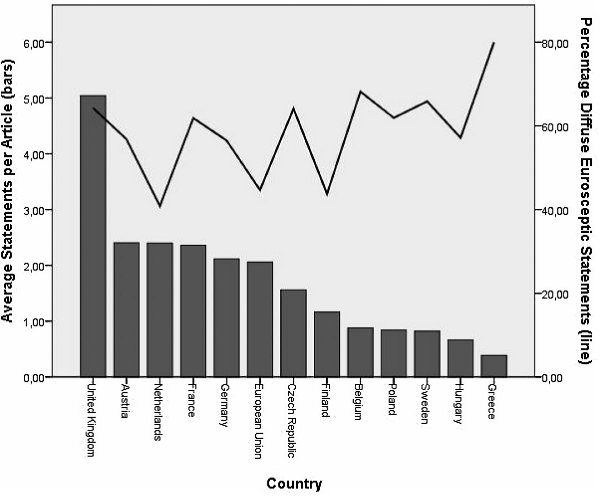

The rising intensity of the debate brings with it a replication of conflicts across different member states. In other words, as the EU becomes hotly contested in some member states – because of austerity imposition or bail-outs of other countries for example – we tend to find similar arguments and even a similar composition of arguments in other member states, even if they are not directly affected. This explains the striking similarity of online discussions across member states and the pervasiveness of diffuse Euroscepticism overall. At the same time, rising intensity of debate about Europe tends to improve the quality of argumentation. That is, the more citizens engage in discussing Europe online, the more specific they become about what it is about Europe that they dislike, what they do like, and which changes might improve the EU. As shown in Chart 2 below, a higher average number of contributions to EU polity contestation per online article corresponds to a slight decrease in diffuse Euroscepticism.

Chart 2: Link between number of comments per online article and the percentage of total comments which exhibit ‘diffuse Euroscepticism’

Note: The bars show the average number of statements/comments per online article for each country, while the line shows the percentage of those statements which fall under the ‘diffuse Eurosceptic’ category.

Note: The bars show the average number of statements/comments per online article for each country, while the line shows the percentage of those statements which fall under the ‘diffuse Eurosceptic’ category.

If political parties campaigning during the upcoming European Parliament elections are interested in representing the will of Europe’s citizens on the issue of ‘more or less Europe’ and look online to find out what citizens want, they face a daunting task. The online citizens’ voice is highly critical of the status quo, without giving much indication as to the desired road ahead. Underlying this diffuse Euroscepticism is a sense of exclusion and disenfranchisement. The only thing making the life of politicians with such intentions easier is the uniform voice of online citizens across member states.

If such party politicians have counterparts in other member states with a similar desire for reforming the EU based on public opinion, online debates indicate that they should find it relatively easy to find a common agenda to campaign upon. But that any reform will actually succeed in making Europe’s citizens more satisfied with the Union is highly unlikely. At least, we do not learn from following online discussions what such a reform should look like.

__________________________

This post has been previously published by the LSE EUROPP Blog.

Pieter de Wilde is Senior Researcher at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center in the Department of Global Governance. After studying political science at the University of Amsterdam, he conducted his PhD at ARENA, Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo, on the politicization of European integration.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Euro Crisis in the Press blog, nor of the London School of Economics.