The Cultural Veil: Iran’s Weaponization of Culture to Oppress Women and Deflect Criticism

Euro Crisis in the Press 2022-05-25

Iran’s legislation of the veil should be seen as a weaponization of culture in order to oppress women. Compulsion and culture are mutually exclusive and cannot exist within the same realm.

On January 8th 1963, Iran’s Reza Shah issued a decree, “kashf-e hijab”, banning all veils and head coverings for women. The law came as an attempt to Westernize the nation, with an emphasis on associating the religious veil as a sign of poverty and rural, non-Iranian culture. Years later, Reza Shah’s son, Mohammad Reza Shah, would lift this ban, and give Iranians freedom of choice in their way of dress. The act would come in an effort to increase popularity, with support for the Shah waning. Finally, at the onset of the Islamic revolution in 1979, soon after taking power, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini decreed that the veil was now mandatory for all Iranian women, along with a strict standard of modest dress. This law continues to be enforced today, with Iranian women lacking the basic freedom of choosing what to wear in public. Despite the fact that the head covering has been worn in Iran for thousands of years, the current mandate has seen backlash from women all over the country, even with its violent enforcement. Yet, for Westerners and non-Iranians alike, the hijab mandate is often dismissed as a factor of culture, written off as a small issue amongst a sea of much larger ones to be addressed. Is this oversimplification of the law an advantage for the Iranian government? An excuse used both within and outside of Iran to dismiss the oppression of women?

In this article, I will focus on Iran’s compulsory hijab law and how the labeling of culture has protected the Iranian government from criticism in this respect and perpetuated their oppression of women and minorities alike. I will discuss the legislation of culture in Iran, specifically targeting women and other marginalized groups, and how culture has been weaponized both towards Iranians, and against criticism from non-Iranians.

What is Culture?

Cultural anthropologists define culture as a shared set of (implicit and explicit) values, ideas, concepts, and patterns of behavior that allow a social group to function and perpetuate itself. Culture is often used as an umbrella term to describe the norms and behaviors of certain groups. In the West, cultural sensitivity has also gained traction as groups are encouraged to respect and understand other cultures, despite how alien it may seem. This generalization of culture and the widespread promotion of cultural sensitivity is important in understanding how culture has been weaponized to oppress in many groups, and specifically in our focus, in Iran. The Islamification of culture throughout the Middle East and North Africa has left the hijab entangled in a web of culture, religion, and politics. The obscurity in the role of the hijab has granted leeway for many governments to weaponize its use and the idea of culture as a whole. In Iran, that is exactly what the government does when it classifies its compulsory hijab law as an aspect of culture.

Iranian Legislation of Culture

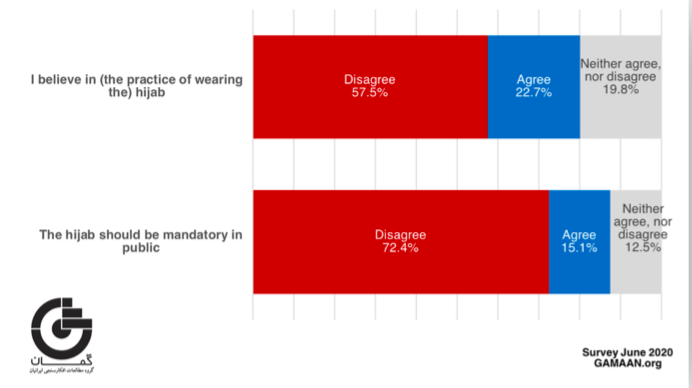

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Iranian government has been embedded with Sharia law and theological ideals. There is no hiding the lack of secularity in the post-revolutionary Iranian government. The islamification of law and government in Iran has led to a gross weaponization of culture and religion to oppress women and other minority groups. The role of the hijab in this legislation began with Reza Shah’s “Kashf-e Hijab” and continues today. When Iranian women are forced to wear the hijab in public, religion and culture is being legislated. The question remains, then, can culture be legislated? If culture is a shared set of values and ideas, then legislating its practice is counterintuitive, as one actively chooses to subscribe to a set of values and ideas. Not only does Iran have a non-Muslim population of some 400,000 but also, according to some surveys, many Muslim citizens are skewing to secularism. The hijab mandate, then, not only takes away women’s choice, it also imposes religion on those who may not be subscribed to it or who choose not to practice. In fact, polls have shown that a majority of the Iranian population does not support the compulsory hijab law. According to a survey done by GAMAAN, The Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran, 72.4% of survey respondents disagreed with the hijab being mandatory in public.

If wearing a hijab was part of the “culture” of Iran, then why aren’t people taking part in the practice voluntarily? A law to mandate the act would not be necessary. Iran’s legislation of culture in this respect is done as a tactic to oppress women and other minorities, rather than maintain culture or religion. Since the Islamic Revolution, many women have resisted the hijab mandate, with protests erupting in Tehran on International Women’s Day in 1979 to more recent global campaigns like My Stealthy Freedom giving Iranian women a voice in their resistance. According to Iranian-American feminist and political scientist Negar Mottahedeh, a key slogan of the post revolutionary women’s movement in Iran was, “we did not have a revolution to take a step backwards.” The Iranian government’s role in controlling women’s appearance has landed on opposite ends of the spectrum throughout history, from forcefully removing the veil to violently imposing it. It is clear that the politicization of the hijab plays a key role in the government’s strategy.

Gender Inequality and the Hijab Law

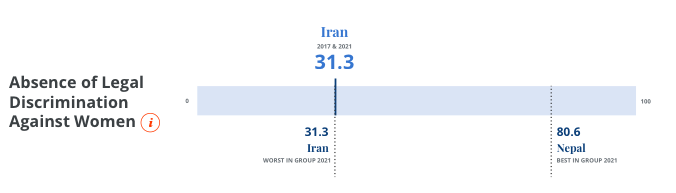

It is imperative to examine the hijab law in the context of severe gender inequality within Iran. The Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security, ranks Iran at 125 out of 170 countries for gender equality. On the scale of “Absence of Legal Discrimination Against Women” done by the same institution, Iran ranked the worst. These facts are important in understanding the larger system of oppression and discrimination that women in Iran face. Iran is continually discriminatory towards women and maintains their status as second class citizens. The compulsory Hijab law, although often dismissed as a minor issue, is a pillar of this larger system. Controlling the very basic rights of women is a main building block in perpetuating their oppression.

A Cultural Shield

The cultural classification of the mandatory hijab law has not only codified women’s oppression, it has also bred a veil of protection from the criticism of outsiders. Criticism of culture is considered culturally insensitive and politically incorrect. Even with the major role that Western countries have played in meddling in Iranian affairs, their newly adopted public attitude of cultural sensitivity has prevented their response to the issue. Many Western politicians have given into the Iranian narrative that the hijab is part of Iranian culture, refusing to comment on the oppressive nature of the compulsory hijab law. Politicians from foreign countries visiting Iran have not resisted wearing the hijab, as a sign of respect to Iranian “culture.” The classification of the hijab law as an aspect of Iranian culture is a key strategy used by the Iranian government to perpetuate its oppression of women. By promoting the idea that the hijab is simply a cultural issue, the non-Iranian world dismisses the relevance of this law in perpetuating an oppressive system against women.

Conclusion

Culture, as it is defined by anthropologists and attempted to be categorized by Iranian politicians, will only be practiced when people are given a choice in doing so. Compulsion and culture are mutually exclusive and cannot exist within the same realm. To deem compulsion as culture is a political tactic used to maintain the system of women’s oppression in Iran. The legislation of culture by the Iranian government through the compulsory hijab law is a weaponization tactic used to oppress, and this must be recognized in order to achieve freedom for Iranian people.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Euro Crisis in the Press blog nor of the London School of Economics.

Jessica Yeroshalmi is currently a third-year student at Macaulay Honors College at Baruch at The City University of New York, pursuing a dual degree in Economics and Political Science. Jessica’s interests include human rights, international history, economics, and politics.