Britain and Euroscepticism: Understanding the Fit

Euro Crisis in the Press 2014-04-10

By Michael Skey

The British population’s views of Europe are shaped by wider attitudes towards Britain’s status and values – unfortunately, for the pro-Europe camp large numbers remain pessimistic and see disengagement as the answer.

Britain’s and Euro-scepticism seem to go together like fish and chips. Polling data consistently show that Britain is the most Eurosceptic country in Europe, with only around 25% of people attached or fairly attached to the EU (compared with a European average of around 45%) while over 70% of Brits said they were ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ attached (the European average is just over 50%). These baseline figures are, of course, important but they sometimes obscure the different attitudes that particular groups in Britain have towards Europe and how these attitudes are shaped by other key factors. What’s more these factors may well influence the ways in which people vote in the forthcoming European elections and any future referendum on membership, should it ever come to pass. I’d like to illustrate this argument by drawing on both qualitative and quantitative data sets, the former coming from my own research and the second produced by the polling group YouGov.

Britain’s and Euro-scepticism seem to go together like fish and chips. Polling data consistently show that Britain is the most Eurosceptic country in Europe, with only around 25% of people attached or fairly attached to the EU (compared with a European average of around 45%) while over 70% of Brits said they were ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ attached (the European average is just over 50%). These baseline figures are, of course, important but they sometimes obscure the different attitudes that particular groups in Britain have towards Europe and how these attitudes are shaped by other key factors. What’s more these factors may well influence the ways in which people vote in the forthcoming European elections and any future referendum on membership, should it ever come to pass. I’d like to illustrate this argument by drawing on both qualitative and quantitative data sets, the former coming from my own research and the second produced by the polling group YouGov.

My own research was interested in the experiences and attitudes of members of the ethnic majority living in England. I conducted 21 group interviews with members of this group, stratified according to class, region and age and asked them general questions such as; ‘what do you dis/like about living here’, ‘what has changed over the past 15 years’, ‘what are the biggest challenges facing the country’ and so on. This type of research isn’t meant to be representative of the population as a whole given the relatively low numbers of people involved, but is able to explore people’s views in a more detailed way by probing their answers and studying people’s interactions. It is also able to trace similarities in the way people look to present and justify their arguments. As part of the discussions, I also asked my respondents about Europe and their responses can be categorised into four broad themes; antagonistic, disinterested, pragmatic, positive.

Given the earlier nod to wider figures on Euroscepticism, it’s perhaps not surprising to learn that a good number of the people I spoke to were antagonistic towards the EU and the project of European integration. They raged against the perceived impact of European legislation and the challenge it presented to British social and political institutions and often made reference to stories they had read or heard in the media.

The second group, the disinterested, did not see European issues as relevant to their own lives and often struggled to think of themselves as European. The following extract, which involves a group of twenty-somethings in north London, offers an illustrative example.

Interviewer: What about Europe, do you consider yourself European at all?

Katie: No. When I think of Europe, I think of other countries.

Fiona: Funnily enough, when I was staying with relatives in America they, like, whereas we when we travel we go to America and places like that, they all go to Europe and they class me in, in Europe and that was weird at the time because I hadn’t really thought of myself as ….

Dave: I’ve never been classified, like, as a European, I’ve never been anywhere outside, like, Europe really (Enfield Group)

This example points to the importance of travel in exposing people to new ways of thinking about their own sense of identity and place, often prompted by engagements with other people and cultures. While increasing numbers are becoming more mobile, we should not, of course, forget that many continue to remain relatively rooted, whether through choice or lack of opportunities. Second, the ‘disinterested’ are a group that may sometimes get overlooked in the ferocious debates between anti and pro-Europeans but there views also need to be acknowledged as they seemed to include a good number of the people I spoke to. In this respect, it’s also worth noting that most of my respondent’s didn’t raise the question of Europe of their own accord but only began discussing it when prompted, which indicates its lack of significance to their own lives.

The views of the first two groups can be usefully contrasted with those who either talked about Europe in more pragmatic terms or welcomed greater integration and identified strongly as European. This was often because they had travelled extensively and saw the benefit of having, for example, a common currency, passport and reduced border controls, or as a positive development, uniting people with shared tastes and values.

Dennis: … I think we should take up the euro.

Kay: Yeah … because it’s a lot cheaper when you going on holiday and you’re having to pay stuff in Europe and there’s a conversion rate and personally and financially you lose out (Doncaster Group)

Some of these features can also be seen in Michael Bruter’s qualitative studies of attitudes towards Europe. He suggests that increased interactions between peoples across Europe and, in particular, the removal of borders is slowly generating a shared – and felt – European experience, albeit haphazardly. Indeed, the increasingly taken-for-granted nature of some of these factors (money, flags, sporting competition, passports, impact of EU legislation) has led Laura Cram to suggest that these everyday activities and features are concretising the ‘idea’ of Europe into a felt reality. Obviously, the structures put in place by the major European political institutions are important but as Cram notes, it is when the impacts and influences of these factors “become the norm … [when] individuals ‘forget to remember’ that the current situation is not how things always were” that ‘Europe’ becomes a taken-for-granted category within people’s lives.

A good example of how these changes are being welcomed by some comes in the following extract from an interview I carried out with a group of middle-class people based in the south-east of England

Andrew: We’re looking at, y’know, the countries of Europe divided vertically. You’ve got, sort of, y’know, English people, Dutch people, French people, Belgium people, and I almost believe it’s not like that, it’s, it’s almost a horizontal division. When you go abroad you meet people who have similar values and interests and .. um .. hobbies as yourself and you get on with those people, regardless of national identity, so it’s in a way, y’know, you find people of a similar nature who happen to be Dutch or French or German and you’d get on fine with them, than you would with people who happen just to be English. I think when you go into it, you really get to know people, the nation, the nationality plays a very small part

This comment indicates the degree to which pan-national solidarities are becoming significant for particular groups in England at the current time. Andrew enunciated the most outward looking perspective of all those I interviewed by focusing on horizontal commitments, that link people by virtue of value, taste and lifestyle, in the process eschewing the more narrow, vertical allegiances most closely associated with the nation. Indeed, this group represented, at least in part, the ideal of the cosmopolitan able and willing to engage with others (in this case Europeans) and their views and experiences offer an important challenge to distinctly national ways of being in and thinking about the world. One further point is worth making here. Members of this group were marked out by being able to speak at least one foreign language having undertaken university-level studies in Europe and by having family members living abroad. In other words, they provide further evidence of the link between a more ‘open’ outlook that moves beyond local or national solidarities and higher levels of mobility, economic capital and education.

If we now return to the quantitative data from YouGov we can see pretty similar patterns. Indeed, Peter Kellner, director of the organisation, identifies three categories, progressive internationalists (25%), pragmatic nationalists (23%) and worried nationalists (42%), which can be mapped onto my own (positive, pragmatic, antagonistic). He also notes that the remaining seven or so percent have no firm opinions and are very unlikely to vote at all – they are disinterested in other words!!

YouGov’s other key finding was that the attitudes of the different groups are profoundly shaped by the way they view Britain’s place in the world. Progressives believe that the country is moving in the right direction and should play a role on the international stage. Unsurprisingly, worried nationalists are far more pessimistic, arguing that Britain is in decline and should disengage from international commitments. Pragmatists fall somewhere between the two, thinking that Britain is doing OK and may need to engage with global institutions at particular moments.

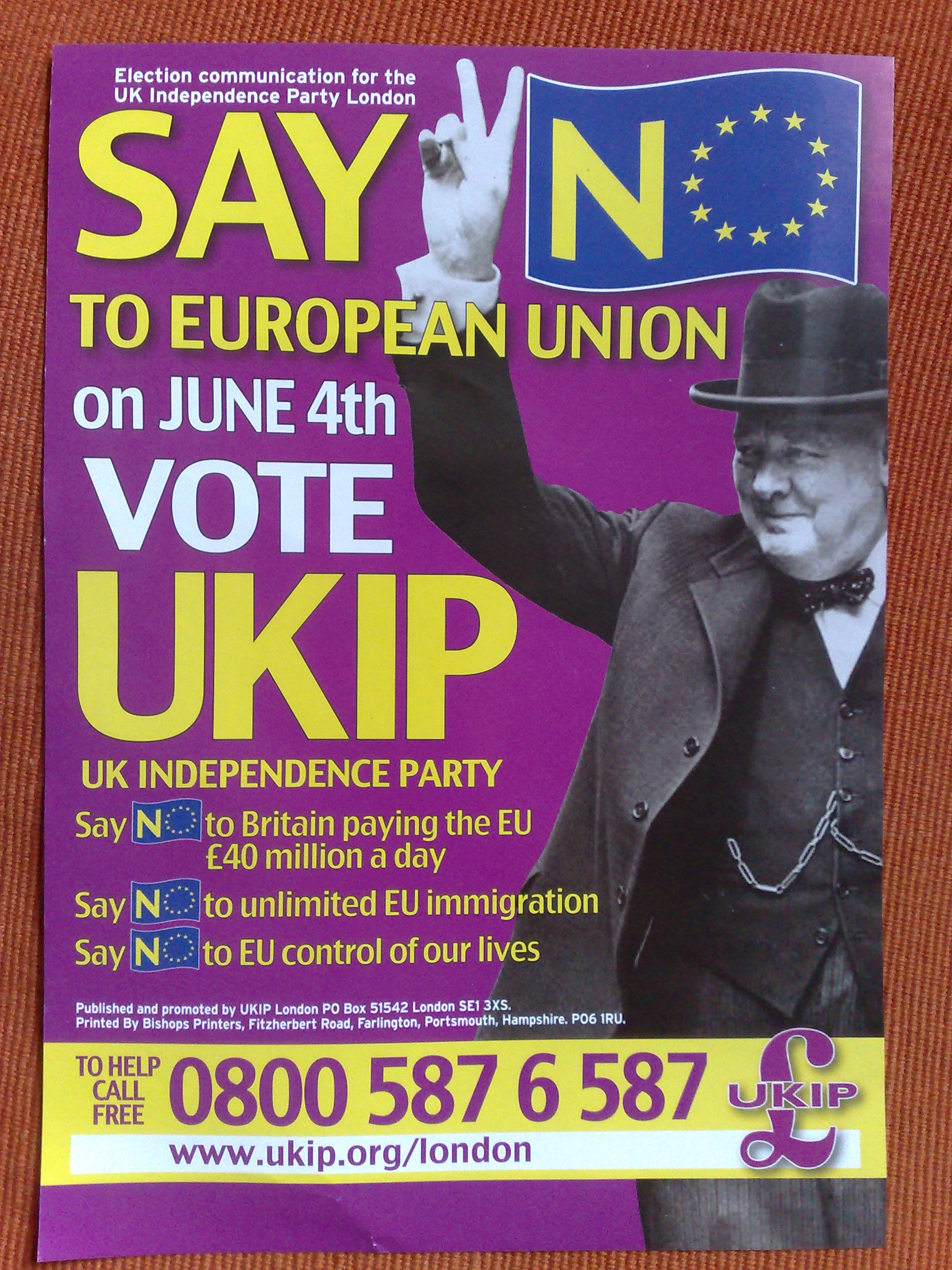

Given these findings, Kellner suggests that the pro and anti-groups can’t formulate their arguments in relation to procedural or legislative issues in order to appeal to voters. Instead, they must look to advocate for their position in relation to Britain’s status and how it might be improved by either engaging with or withdrawing from Europe. The key problem for pro-Europeans is the historically low turn-out for European elections and the extent to which voting in them is increasingly skewed towards older generations and the more politically engaged. In the former case, it is the over 40’s who tend to be more pessimistic and Eurosceptic. Indeed, they are the group who vote for UKIP in the largest numbers. In the latter, one might argue that passionate Europhiles are also motivated to vote, but even if they are, there are not enough of them to swing the result their way. As a result, their only real chance of winning is to motivate enough pragmatists to vote as well as changing the minds of a few worriers. This seems increasingly unlikely in the current political climate.

_______________

This article was originally published by the University of East Anglia’s Eastminster blog

Dr. Michael Skey is a Lecturer in Media and Culture at the University of East Anglia. His monograph entitled ‘National Belonging and Everyday Life’ (published in 2011 by Palgrave) was joint winner of the 2012 BSA/Phillip Abrams Memorial Prize.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Euro Crisis in the Press blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

________________

Related articles on LSE Euro Crisis in the Press:

Farage is right – it’s not just the economy, stupid!

Nordic Euroscepticism – An Exception that Disproves the Rule?