Book Review: Dispossession: The Performative in the Political

EUROPP 2013-09-02

In the last several years, the world has been rocked by historic protests, from Zucotti Park to Syntagma Square, and from the Arab Spring to the Greek Uprising. In Dispossession: The Performative in the Political, Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou investigate the concept of dispossession and its connections with recognition, performativity, bio-politics, protest, and relationality. Cody Campbell found the book to be an enjoyable read, and particularly liked the chemistry between the two authors, but worries that those looking for a more concrete analysis of dispossession and its relationship to performativity may walk away disappointed.

In the last several years, the world has been rocked by historic protests, from Zucotti Park to Syntagma Square, and from the Arab Spring to the Greek Uprising. In Dispossession: The Performative in the Political, Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou investigate the concept of dispossession and its connections with recognition, performativity, bio-politics, protest, and relationality. Cody Campbell found the book to be an enjoyable read, and particularly liked the chemistry between the two authors, but worries that those looking for a more concrete analysis of dispossession and its relationship to performativity may walk away disappointed.

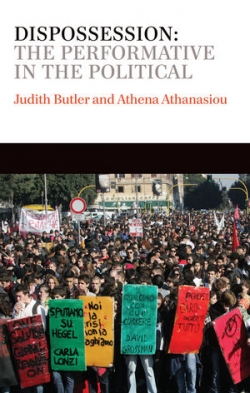

Dispossession: The Performative in the Political. Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou. Polity. February 2013.

Judith Butler has a long and distinguished history of exploring the performativity of gender, dating back to her classic, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, which has become a mainstay in Gender Studies curricula. In Dispossession: The Performative in the Political, she joins forces with Athena Athanasiou, a young feminist scholar from the Department of Social Anthropology at Panteion University in Greece, to explore the wide-ranging potentialities latent in the performance of identity.

In the form of a dialogue, the book was written (primarily via email) during the height of the Egyptian Revolution and the Greek uprising; the effect produced is one of collegial discourse. Imagine Butler and Athanasiou discussing their ideas during a panel at a conference. This dialogic form necessarily restricts the depth to which much of the conversation can go; many of the chapters could be elaborated into book-length theses themselves. There’s both an upside and downside to this. For those familiar with Butler and/or Athanasiou’s work, Dispossession will feel like the preliminary groundwork needed for a larger project; some of the chapters had me yearning for a much more in-depth discussion. On the other hand, the conversational tone lends itself well to those unfamiliar with the authors’ previous work; and by framing their conversation within current political crises (Zucotti Park, Cairo, Israel/Palestine, Greece, etc.) Dispossession positions itself as a timely tool for protesters and activists.

Together, Butler and Athanasiou set out to “think about dispossession outside the logic of possession” (p.7). In other words, they unearth the myriad forces that lead to dire issues of dispossession (forced migration, colonialism, homelessness, etc.) without falling back on the neo-liberal discourse of property and ownership as the primary factors of subjectivity. Rather, they argue that there is a limit to self-sufficiency, and it’s at this threshold of autonomy that we can see ourselves as relational and interdependent beings. We are thus always-already dispossessed of ourselves, bound together through a constitutive self-displacement.

The “Sovereign I” of western philosophical, political and economic discourse is thus turned on its head, as the authors walk the fine line of lauding the self-dispossession of relationality without it crumbling into an excuse for the neo-liberal humanitarian and human rights discourses that act as insidious support structures for economic and colonial dispossession. After all, if we are always-already self-dispossessed, the humanitarian industrial complex has no reason to critique the economic, social, and political structures that produce dispossession, which then amounts to little more than instances of injustice. We should be wary not to miss the forest for the trees.

These concepts of dispossession seem to be merely a foundation for the question the authors are really interested in, though, and which takes up the second half of the book: what makes political responsiveness possible? After sketching the outlines and many of the over-determined formations of being-dispossessed, they quickly move on to question the ways in which performativity can act as political resistance. From this point forward I found myself wishing the authors had narrowed their vision slightly.

Occupy Wall Street takes over Washington Square Park, August 2011. Credit: Darwin Yamamoto CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The wide range of references and examples that dot the pages of Dispossession – Australia’s indigenous population, Palestinians and Israelis, Occupy Wall Street, LGBTQ people, colonized persons in North Africa, women in South Asia, and the list goes on – makes the book rather unwieldy and difficult to take full grasp of. The authors seem to want to critique all the world’s injustices through rather narrow temporal lenses. Early on, Butler warns against collapsing particular histories into each other (p.13), but that advice doesn’t seem to register througought the rest of the book. For example, near the end of Dispossession, Butler conflates the “UK Riots” with Occupy Wall Street as “demonstrations without demands.” Due to the complicated nature of the UK protests (wasn’t it in response to the killing of a young black man?) I’m uncomfortable saying that it had no demands. As Butler hints, there are very particular histories that inform these two movements, and they seem to demand particular critiques.

That said, Dispossession is full of fantastic and well-argued insights. In chapter 3, “A Caveat about the ‘primacy of economy,’” Athanasiou makes a compelling case against the “economistic orthodoxy” of the Left, recalling the vigorous debates between Butler and Nancy Fraser of the 1990s. Being careful not brush aside economic matters, though, Athanasiou formulates the problem as such: “there’s nothing merely economic about economics.” Disturbing the hegemony of neo-liberal capitalism itself requires “opening up conceptual, discursive, affective and political spaces for enlarging our economic and political imaginary,” Athanasiou points out. Here we can see – both explicitly and implicitly – how deeply Foucault’s conception of bio-politics informs their critique and grounds their call for a political responsiveness embedded in performativity.

Dispossession also goes a long way in bringing together previous work done by various critical theorists and feminists on the concept of recognition with Butler and Athanasiou’s ideas about performativity, particularly in Chapter 7, “Recognition and survival, or surviving recognition.” Personhood and subjectivity are tightly wound around the social and cultural act of recognition: recognizing in the “other” norms of intelligibility, which govern models of marriage, conceptions of the masculine and the feminine, as well as cultural and economic identities. Radical performance itself lies in the act of unsettling such norms of intelligibility – and because of that, such performance also inaugurates a sense of radical precarity: my relationality to others is what constitutes me as an interdependent subject, and disturbing the tenuous norms of intelligibility by which others can and do recognize me as part of a collective social fabric leaves me increasingly vulnerable.

All in all, the combination of Butler and Athanasiou made for an enjoyable read. The two brought their own unique and incisive styles, each playing off the other in exciting and unsuspected ways. The authors were strongest when conceptualizing about dispossession outside the logic of possession, and scholars or activists who are interested in questions of performativity and recognition will find a lot to like. Those looking for a more concrete analysis of material or territorial dispossession in its relationship to performativity may walk away disappointed.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/17wXDKW

_________________________________

Cody Campbell Cody Campbell is a PhD student in Political Theory at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York City, where he studies the History of Political Thought, and Comparative and American Politics. He received his MA in Philosophy from Stony Brook University, where he also earned a BA studying Philosophy and Literature. He is particularly interested in the construction of political identities, and how they are manifested, sustained, and ruptured through cultural production.

Cody Campbell Cody Campbell is a PhD student in Political Theory at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York City, where he studies the History of Political Thought, and Comparative and American Politics. He received his MA in Philosophy from Stony Brook University, where he also earned a BA studying Philosophy and Literature. He is particularly interested in the construction of political identities, and how they are manifested, sustained, and ruptured through cultural production.

Related posts:

- Book Review: Political Parties in Britain

- Book Review: Politics and the Emotions: The Affective Turn in Contemporary Political Studies

- Book Review: History of Political Theory: An Introduction. Volume 1: Ancient and Medieval Political Theory

Find this book:

Find this book: