Bridging Tech-Military AI Divides in an Era of Tech Ethics: Sharif Calfee at CITP

Pinboard (datasociety) 2019-02-06

In a time when U.S. tech employees are organizing against corporate-military collaborations on AI, how can the ethics and incentives of military, corporate, and academic research be more closely aligned on AI and lethal autonomous weapons?

Speaking today at CITP was Captain Sharif Calfee, a U.S. Naval Officer who serves as a surface warfare officer. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and U.S. Naval Postgraduate School and a current MPP student at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Afloat, Sharif most recently served as the commanding officer, USS McCAMPBELL (DDG 85), an Aegis guided missile destroyer. Ashore, Sharif was most recently selected for the Federal Executive Fellowship program and served as the U.S. Navy fellow to the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments (CSBA), a non-partisan, national security policy analysis think-tank in Washington, D.C..

Sharif spoke to CITP today with some of his own views (not speaking for the U.S. government) about how research and defense can more closely collaborate on AI.

Over the last two years, Sharif has been working on ways for the Navy to accelerate AI and adopt commercial systems to get more unmanned systems into the fleet. Toward this goal, he recently interviewed 160 people at 50 organizations. His talk today is based on that research.

Sharif next tells us about a rift between the U.S. government and companies/academia in AI. This rift is a symptom, he tells us, of a growing “civil-military divide” in the US. In previous generations, big tech companies have worked closely with the U.S. military, and a majority of elected representatives in Congress had prior military experience. That’s no longer true. As there’s a bifurcation in the experiences of Americans who serve in the military versus those who have. This lack of familiarity, he says, complicates moments when companies and academics discuss the potential of working with and for the U.S. military.

Next, Sharif says that conversations about tech ethics in the technology industry are creating a conflict that making it difficult for the U.S. military to work with them. He tells us about Project Maven, a project that Google and the Department of Defense worked on together to analyze drone footage using AI. Their purpose was to reduce the number of casualties to civilians who are not considered battlefield combatants. This project, which wasn’t secret, burst into public awareness after a New York Times article and a letter from over three thousand employees. Google declined to renew the DOD contract and update their motto.

U.S. Predator Drone (via Wikimedia Commons)

On the heels of their project Maven decision, Google also faced criticism for working with the Chinese government to provide services in China in ways that enabled certain kinds of censorship. Suddenly, Google found themselves answering questions about why they were collaborating with China on AI and not with the U.S. military.

How do we resolve this impasse in collaboration?

- The defense acquisition process is hard for small, nimble companies to engage in

- Defense contracts are too slow, too expensive, too bureaucratic, and not profitable

- Companies aren’t not necessarily interested in the same type of R&D products as the DOD wants

- National security partnerships with gov’t might affect opportunities in other international markets.

- The Cold War is “ancient history” for the current generation

- Global, international corporations don’t want to take sides on conflicts

- Companies and employees seek to create good. Government R&D may conflict with that ethos

Academics also have reasons not to work for the government:

- Worried about how their R&D will be utilized

- Schools of faculty may philoisophically disagree with the government

- Universities are incubators of international talent, and government R&D could be divisive, not inclusive

- Government R&D is sometimes kept secret, which hurts academic careers

Faced with this, according to Sharif, the U.S. government is sometimes baffled by people’s ideological concerns. Many in the government remember the Cold War and knew people who lived and fought in World War Two. They can sometimes be resentful about a cold shoulder from academics and companies, especially since the military funded the foundational work in computer science and AI.

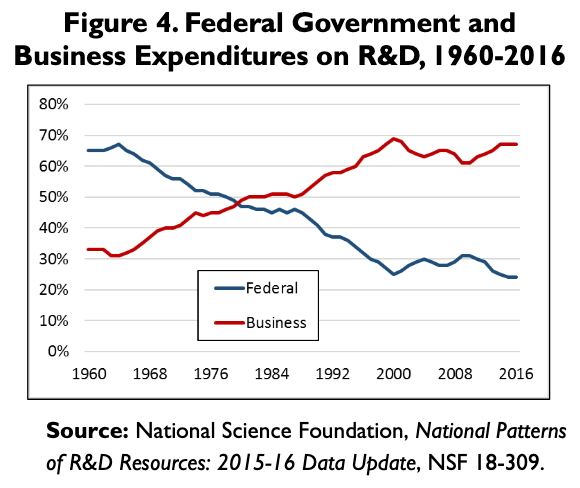

Sharif tells us that R&D reached an inflection point in the 1990s. During the Cold War, new technologies were developed through defense funding (the internet, GPS, nuclear technology) and then they reached industry. Now the reverse happens. Now technologies like AI are being developed by the commercial sector and reaching government. That flow is not very nimble. DOD acquisition systems are designed for projects that take 91 months to complete (like a new airplane), while companies adopt AI technologies in 6-9 months (see this report by the Congressional Research Service).

Conversations about policy and law also constrain the U.S. government from developing and adopting lethal autonomous weapons systems, says Sharif. Even as we have important questions about the ethical risks of AI, Sharif tells us that other governments don’t have the same restrictions. He asks us to imagine what would have happened if nuclear weapons weren’t developed first by the U.S..

How can divides between the U.S. government and companies/academia be bridged? Sharif suggests:

- The U.S. government must substantially increase R&D funding to help regain influence

- Establish a prestigious DOD/Government R&D one-year fellowship program with top notch STEM grads prior to joining the commercial sector

- Expand on the Defense Innovation Unit

- Elevate the Defense Innovation Board in prominence and expand the project to create conversations that bridge between ideological divides. Organize conversations at high levels and middle management levels to accelerate this familiarization.

- Increase DARPA and other collaborations with commercial and academic sectors

- Establish joint DOD and Commercial Sector exchange programs

- Expand the number of DOD research fellows and scientists present on university campuses in fellowship programs

- Continue to reform DOD acquisition processes to streamline for sectors like AI

Sharif has also recommended to the U.S. Navy that they create an Autonomy Project Office to enable the Navy to better leverage R&D. The U.S. Navy has used structures like this for previous technology transformations on nuclear propulsion, the Polaris submarine missiles, naval aviation, and the Aegis combat system.

At the end of the day, says Sharif, what happens in a conflict where the U.S. does not have the technological overmatch and is overmatched by someone else? What are the real life consequences? That’s what’s at stake in collaborations between researchers, companies, and the U.S. department of defense.