FDCA doesn't preclude lawsuit based on allegedly false claims about compounding drugs

Rebecca Tushnet's 43(B)log 2024-08-28

Pacira Biosciences, Inc. v. Nephron Sterile CompoundingCenter, LLC, No. 3:23-5552-CMC, 2024 WL 3656489 (D.S.C. Jul. 15, 2024)

Pacira, which sells non-opioid pain management products, includingExparel, sued Nephron for false advertising. Exparel is “bupivacaine suspendedin multivesicular liposomes,” and is injected at a surgical site during orshortly after surgery to manage and reduce post-surgical pain.

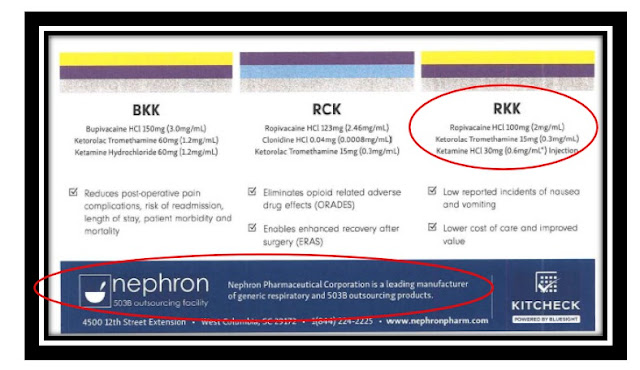

Nephron allegedly operates a compounding pharmacy thatcompounds BKK, comprised of ketorolac, ketamine, and bupivacaine in a syringefor combined use, and RKK, a compounded drug consisting of syringes ofketorolac, ketamine, and ropivacaine for combined use.

Compounded drugs are not FDA-approved, but may be made andsold under certain circumstances, including rules about outsourcing facilities,which may not compound using bulk drug substances unless the bulk drugsubstances are on a relevant FDA list of clinical need/shortage drugs.

Pacira alleged that the production of BKK and RKK was not coveredby the FDCA’s protection for compounded drugs because (1) BKK and RKK do notappear on the FDA’s drug shortage list, and (2) the bulk drug substances fromwhich BKK and RKK are made do not appear on the FDA’s list of bulk drugsubstances for which there is a clinical need. But, of course, the FDCA may notbe enforced by private parties, so Pacira turned to the Lanham Act.

Thus, Pacira alleged that defendants “have engaged in asustained campaign to promote their drug cocktail products as safe andeffective opioid alternatives through demonstrably false and misleadingadvertisements – including blatantly false statements that their drugs aresafer and more effective than EXPAREL.” They also allegedly claimed or impliedthat BKK and RKK compounds have been approved by the FDA and/or subjected toclinical studies and trials.

Caption: Nephron is fully inspected and approved by the FDA!

Caption: Nephron is fully inspected and approved by the FDA!  Footer with FDA approved logo

Footer with FDA approved logoNephron argued that its website was not false: The allegedlydeceptive statements, a “Nephron is fully inspected and approved by the FDA!”banner and “FDA APPROVED” logo at the foot of Nephron’s website appeared in thesame place on every page of Nephron’s website, including its landing page. Itargued that, in context, the banner and footer, which included other logos,such as “MADE IN U.S.A.,” obviously referenced only Nephron, and Nephron is, infact, a registered 503B outsourcing facility both certified and regularlyinspected by the FDA. Anyway, it argued, implicit misrepresentations of FDAapproval weren’t actionable.

Pacira responded that (1) the FDA doesn’t approve facilities,(2) the statements would be attributed to BKK and RKK’s FDA approval, (3)customers looking for information on those specific products wouldn’tnecessarily peruse every page to see what repeats, and (4) “Made in the USA” isthe kind of statement that consumers would attribute to the products, notthe facilities, so the footer logos encouraged confusion rather than diminishedit.

Despite the plausibility of these arguments, the courtadopted the rule that “the law does not impute representations of governmentapproval ... in the absence of explicit claims.”

example of product benefit claims for pain, complications, etc.

example of product benefit claims for pain, complications, etc.  slide specifically claiming superiority to Exparel and identifying it as "competition"

slide specifically claiming superiority to Exparel and identifying it as "competition"Allegedly false claims to hospitals and providers inpresentation and other marketing materials about the efficacy, safety, andsuperiority of BKK and RKK: First, it was plausible to attribute those to Nephronbecause it hired the person who created the slide show and conducted thepresentations. He allegedly “not only developed advertisements and marketingmaterials for BKK, but he also actively participated in sales pitches and otherpromotional events nationwide to sell.” This was enough at the pleading stageto impute his actions to Nephron. However, the same “implicit misrepresentationof government approval” rule applied to FDA-approval-related claims. But Paciraalso alleged that claims of improved patient safety, satisfaction, recoverytime, outcomes, and patient experience were false and misleading. It alsoalleged that Nephron’s superiority claims, including that BKK and RKK are more“efficacious for long term analgesia” and “post operative pain” than Exparelwere literally false. At this stage, the allegations were sufficient as to thesafety, efficacy, etc. statements.

footer claiming that Nephron is a 503B outsourcing facility

footer claiming that Nephron is a 503B outsourcing facility  503B outsourcing facility claim as part of Nephron logo

503B outsourcing facility claim as part of Nephron logoSomewhat puzzlingly to me, the court also allowed claimsbased on the idea that the logo indicating Nephron is a 503B outsourcingfacility conveys the false impression that BKK and RKK products are produced bya 503B-compliant facility. A facility isn’t compliant if it compounds drugs itshouldn’t, and Pacira alleged that this was the case. “Nephron’s claim it is a503B outsourcing facility, even if true, could falsely imply BKK and RKKsatisfy the requirements of § 353b, if, indeed, they do not.” Pacira alsoalleged reasonable consumer reliance on the misrepresentation by alleging that,“[o]n information and belief, healthcare providers and consumers havereasonably relied on Defendants’ false and misleading statements when decidingto purchase BKK or RKK instead of EXPAREL” and that if they’d known the truth,they wouldn’t have bought the drugs.

What about “commercial advertising or promotion”? Nephronobjected that Pacira didn’t define the relevant market or allege to whom thepresentations were disseminated. First, the statements were commercial speechpromoting Pacira’s products that were provided to a relevant market –healthcare providers. But were such “product overview” statements in presentationsjust medical education? No; “it would strain credulity to find Nephron did notintend to turn a profit convincing its target audience to purchase BKK and RKK.”

Pacira sufficiently alleged injury.

Were the Lanham Act claims precluded by the FDCA? Nephronargued that it could only be found to be falsely advertising if the courtinterpreted the FDCA and determined that it was violating the compoundingregulations, but that interpretation/determination is for the FDCA. [Side note:does this argument work in an age of lack of deference to agencies? Especiallyif the question is what conduct satisfies the legal standard set out in the law?Without Chevron, is a decision really committed to the FDA, or to acourt? I think I just found an interesting student note topic.]

Pom Wonderful LLC v. Coca-Cola Co., 573 U.S. 102 (2014), providesthe governing law. [This isn’t really correct—Pom involved a deceptiontheory that didn’t rely on the FDA’s rules and Coca-Cola argued that itscompliance with FDA’s rules precluded the deception theory. Here, the deceptiontheory does rely on the FDA’s rules.] The court here relied on Pom’spolicy-based reasoning: The FDA is for health and safety, not primarilyconsumer protection; the Lanham Act is primarily about consumer protection. TheFDA lacks expertise in assessing whether people are deceived. [Again, while I’msubstantively in sympathy with Pacira on the policy, that may be true—but theFDA is the expert on whether compounding facilities are complying withits rules, which is factual key to this specific theory of deception.] Thus,while characterizing defendant’s conduct as “illegal,” “unlawful,” and posing“significant risks to patient safety and health” in the complaint was “overzealous”because it could “implicate the need for enforcement by the FDCA,” the gravamenof Pacira’s allegations were falsity and misleadingness and resulting harm toPacira.