Privy Council’s Role in Cancelling Patents Around 1791

Patent – Patently-O 2017-08-21

In my view, a potential critical historical question in Oil States is whether the English Privy Council was empowered to revoke patents back in 1791.

For many years leading up to its last cancellation action in 1779, the Privy Council operated as a kind of administrative body empowered to revoke or void issued patent rights on signature of a sufficient number of Privy Council members. If the Privy Council was empowered in the 1790s to cancel issued patents without judge or jury, that suggests that – in today’s world of expanded administrative power – Congress can also empower a the PTO to cancel issued patents. Some folks may reflect that – although Old English Law matters for the Seventh Amendment jury trial issue, it is much less critical for the administrative law question. Others will also argue that the Privy Council approach was entirely rejected by Americans when we rejected the notion of American Royalty. I’ll slide by these points for this point and instead look at uncovering some Privy Council history.

If we begin with recognizing that the Statute of Monopolies indicated that patents should be tried by the courts, one explanatory theory for the Privy Council’s power is that English patent rights always included a caveat that permitted patents to be cancelled by the Council as an alternative avenue. Certainly, the Privy Council was active in these proceedings prior to 1779.

A 1904 treatise titled The English Patent System (by William Martin) states that, although Privy Council had not taken any recent actions, the Patents Law Amendments Acts of 1852 and 1902 each include a proviso allowing granted patents to be revoked by the Privy Council:

A 1904 treatise titled The English Patent System (by William Martin) states that, although Privy Council had not taken any recent actions, the Patents Law Amendments Acts of 1852 and 1902 each include a proviso allowing granted patents to be revoked by the Privy Council:

Although the Statute of Monopolies declared that patent grants should be tried in the courts of common law “and not at the Council Table,” this power continued to be inserted in patents. Even at the present day the statutory form of the patent, as also that enacted for the first time in 1852, contains a similar proviso against prejudice and inconvenience “to our subjects in general.” This proviso after having lain dormant for centuries has received statutory recognition in the Patents Act of 1902. By this Act the Privy Council is empowered to revoke a patent in the event of an existing industry or the establishment of a new industry being unfairly prejudiced.

I have not yet personally reviewed these acts to know whether Martin’s statement is correct. (Anyone?). Minor note here that I believe Oren Bracha in his book Owning Ideas: A History of Anglo-American Intellectual Property (n.35) mistakenly interprets this passage to say that “revocation clauses authorizing the Privy Council to revoke patents were continued to be inserted in the patent grants up to 1902.” However, I also have not reviewed pre-1902 English patent grants for these revocation clauses (Anyone?).

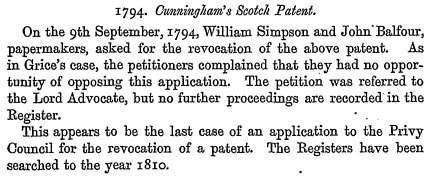

An additional historical point comes from a sources citing one a final, albeit unsuccessful, “petition to the Council to vacate a patent in 1794.” D. Seaborne Davies, Early History of the Patent Specification, 50 L.Q.R. 88-109 (1934) (citing Privy Council Registers, Vol. 141, p.88); E. Wyndham Hulme, Privy Council Law and Practice of Letters Patent for Invention from the Restoration to 1794, 33 L.Q.R 63, 181 (1917). Hulme explains:

The historical record is thus starting to suggest that, although the Privy Council took no action to cancel patents after 1779, it may have been empowered to do so throughout the 18th and 19th Centuries. At this point, I don’t have any further take-away conclusions and would be receptive to comments and guidance.